JENA, Germany — Written language dates back thousands of years. Facilitating literature, law, and everything in between, the written word exemplifies civilization itself. So, where did it begin and how did it evolve? A near 200-year-old African language is shedding some much-needed light on the evolution of writing.

Scientists at the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History analyzed the Vai script of Liberia, a rare African writing system that has fascinated and puzzled researchers since the early 19th century. Their work suggests new ways of writing quickly become “compressed” to clear the way toward more efficient reading and writing.

Like much of ancient history, the true origins of writing will likely remain a mystery forever. We know that writing was probably first invented in the Middle East about 5,000 years ago, forgotten for centuries, and then re-invented in both China and Central America. Fast forward to the 1830s, and a handful of people created the Vai script.

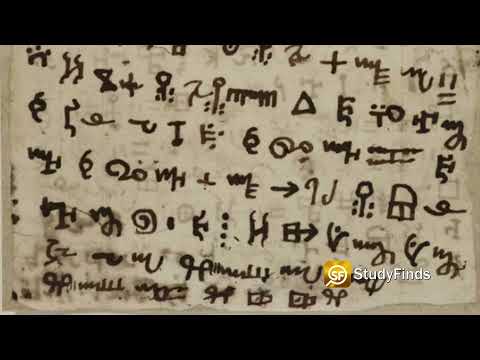

“The Vai script of Liberia was created from scratch in about 1834 by eight completely illiterate men who wrote in ink made from crushed berries,” says lead author Dr. Piers Kelly, now at the University of New England, Australia, in a media release.

Pictures evolved into letters

The Vai script is typically taught in an informal manner by a literate teacher to a single apprentice student, explains Vai expert Bai Leesor Sherman. The Vai writing system persists and is actually quite popular on a local level to this day. Currently, people use it to communicate pandemic health recommendations.

“Because of its isolation, and the way it has continued to develop up until the present day, we thought it might tell us something important about how writing evolves over short spaces of time,” Dr. Kelly explains. “There’s a famous hypothesis that letters evolve from pictures to abstract signs. But there are also plenty of abstract letter-shapes in early writing. We predicted, instead, that signs will start off as relatively complex and then become simpler across new generations of writers and readers.”

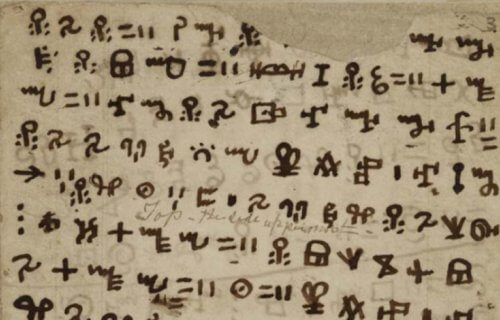

Researchers analyzed Vai manuscripts provided by Liberian, American, and European archives. By investigating year-by-year changes in Vai’s 200 syllabic letters, the research team was able to trace the script’s entire evolutionary history (1834-present day). Through the application of computational tools measuring visual complexity, researchers discovered that Vai’s individual letters really did become visually simpler with each passing year.

“The original inventors were inspired by dreams to design individual signs for each syllable of their language. One represents a pregnant woman, another is a chained slave, others are taken from traditional emblems. When these signs were applied to writing spoken syllables, then taught to new people, they became simpler, more systematic and more similar to one another,” Dr. Kelly continues.

Written language continues to evolve today

Study authors say you can see similar, gradual patterns of letter simplification in ancient writing systems as well.

“Visual complexity is helpful if you’re creating a new writing system. You generate more clues and greater contrasts between signs, which helps illiterate learners. This complexity later gets in the way of efficient reading and reproduction, so it fades away,” Dr. Kelly concludes.

Moving forward, Africa may provide many more answers regarding the usual trajectory of the evolving written word. For example, people in Nigeria and Senegal are still inventing new writing systems to this day.

“African indigenous scripts remain a vast, untapped repository of semiotic and symbolic information. Many questions remain to be asked,” notes Nigerian philosopher Henry Ibekwe.

The findings appear in the journal Current Anthropology.