Scientists say the deep-learning system, called SSCAR, is ‘significantly’ more accurate than doctors’ predictions.

BALTIMORE — Groundbreaking technology can now predict if — and when — someone will suffer a potentially fatal cardiac arrest. The first-of-its-kind survival predictor can detect patterns in a patient’s heart invisible to the naked eye.

Scientists at Johns Hopkins University say that the new artificial intelligence-based approach can predict “significantly more accurately” than a doctor if and when a patient could die of cardiac arrest. The technology, built on raw images of patient’s hearts and patient backgrounds, stands to revolutionize clinical decision making and increase survival from sudden and lethal cardiac arrhythmias, one of medicine’s deadliest and most puzzling conditions.

The deep learning technology is called Survival Study of Cardiac Arrhythmia Risk (SSCAR). The name alludes to cardiac scarring caused by heart disease that often results in lethal arrhythmias, and the key to the algorithm’s predictions.

“Sudden cardiac death caused by arrhythmia accounts for as many as 20 percent of all deaths worldwide and we know little about why it’s happening or how to tell who’s at risk,” says study senior author Natalia Trayanova, a professor of biomedical engineering and medicine, in a statement. “There are patients who may be at low risk of sudden cardiac death getting defibrillators that they might not need and then there are high-risk patients that aren’t getting the treatment they need and could die in the prime of their life. What our algorithm can do is determine who is at risk for cardiac death and when it will occur, allowing doctors to decide exactly what needs to be done.”

The team is the first to use neural networks to build a personalized survival assessment for each patient with heart disease. Trayanova says the risk measures provide with high accuracy the chance for a sudden cardiac death over 10 years, and when it’s most likely to happen.

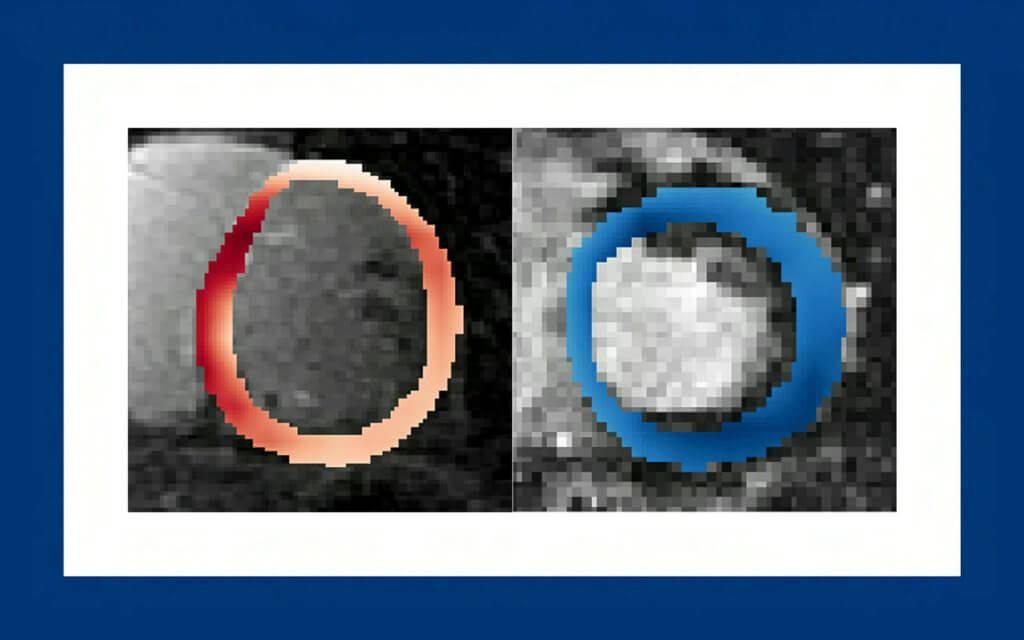

The team used contrast-enhanced cardiac images that visualize scar distribution from hundreds of real patients at Johns Hopkins Hospital with cardiac scarring. This trained an algorithm to detect patterns and relationships not visible to the naked eye.

Current clinical cardiac image analysis extracts only simple scar features such as volume and mass, severely underutilizing what’s demonstrated in the work to be critical data. The images carry critical information that doctors haven’t been able to access.

“This scarring can be distributed in different ways and it says something about a patient’s chance for survival. There is information hidden in it,” says first author Dan Popescu, a former Johns Hopkins doctoral student.

The team trained a second neural network to learn from 10 years of standard clinical patient data. It analyzed 22 factors, such as patients’ age, weight, race and prescription drug use.

The algorithms’ predictions were not only significantly more accurate on every measure than doctors, they were validated in tests with an independent patient group from 60 health centers around the United States, with different cardiac histories and different imaging data. This suggests the platform could be adopted anywhere.

“This has the potential to significantly shape clinical decision-making regarding arrhythmia risk and represents an essential step towards bringing patient trajectory prognostication into the age of artificial intelligence,” says Trayanova.. “It epitomizes the trend of merging artificial intelligence, engineering, and medicine as the future of healthcare.”

She says the team is now working to build algorithms to detect other cardiac diseases. They believe the deep-learning concept could be developed for other fields of medicine that rely on visual diagnosis.

The findings are published in the journal Nature Cardiovascular Research.

South West News Service writer Stephen Beech contributed to this report.

It would be an advance to know when someone will suffer cardiac arrest. However, the answer to the “if” part has been available for a long time and I can tell you that answer for anyone without even seeing the person. Yes, that person will suffer cardiac arrest. We all die and cardiac arrest is the definition of death.

Been a non doctor long ? Cardiac Arrest is NOT the definition of death .

Well, if your heart stops, that is the show-stopper, isn’t it? Pretty much everything else follows from lack of circulation – EEG measurements from the brain, or no, if there is no blood, the brain doesn’t last too long.

Fortunately for us and unfortunately for Johns Hopkins we have been conducting predictive cardio events successfully for 4 years using our now patented telemedicine platform in beta. We use a pulse-oximeter blue toothed to ones PDA or laptop connected to our website to conduct a 30 point real time analysis to be transmitted to the physician, patient, and/or our proprietary EMR/PHR now under construction also with zero trust cyber security inside a decentralized data management private network. Using the heartbeat as a biometric patient ID authentication eliminates the need for passwords, sign in, etc., and layering 3D communications for the user experience is ushering in a whole new level of remote monitoring and telemedicine deployment. We developed in stealth starting in 2007 and in earnest in 2018 anticipating predictive analytics and health maintenance would eventually become sacrosanct for reducing unnecessary cost of care by reducing catastrophic and debilitating events. Good to see institutions catching up to entrepreneurial dedication and perseverance.

“we have been conducting predictive cardio events” should read “predictive cardio monitoring without diagnostic recommendations”

Yeah, I’m gonna trust a computer.

You know… I’m something of a pattern detector myself.

I’ve been studying historical patterns involving both war and organized crime.

One heuristic that I employ is to always ask myself key questions: Who, What, When, Where, Why, How, How Frequently, How Much, and so on…

When I ask myself these questions, I like to gain a lot of concrete knowledge about the thing about which I am learning.

Take for instance the real causes of WWII. Look at the creation of the various organizations for labor and professional work. Who are the financiers, the controllers, the beneficiaries. What are the means of motivation, the standard of rhetoric, the mechanisms of control. What are the results? We are living in them, but I have found many in the “who” category have names, addresses, and very pronounced opinions about matters on which they censor those who disagree with them.