AUSTIN, Texas — We’re all waiting with bated breath for some good news on a COVID-19 vaccine or other form of treatment. Luckily, help may soon be on the way thanks to an unexpected friend: a llama named Winter. An international team of researchers say that an antibody found in llamas is the key to creating an effective way to neutralize the coronavirus.

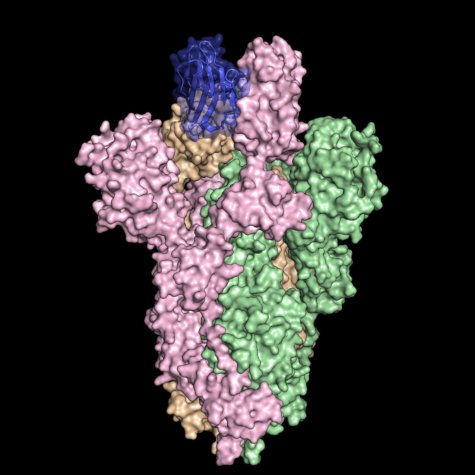

The researchers, from the University of Texas at Austin, the National Institutes of Health, and Ghent University in Belgium, took two copies of a special antibody only found in llamas, and used them to create a brand new antibody capable of binding to and neutralizing a coronavirus spike protein. That spike protein is what allows the coronavirus to attach itself to host cells.

Initial tests of infected cells using this new llama-produced antibody have already shown great promise.

“This is one of the first antibodies known to neutralize SARS-CoV-2,” says co-senior study author Jason McLellan, associate professor of molecular biosciences at UT Austin, in a release.

Clinical trials involving hamsters and primates are already being planned, and hopefully, that will lead to human trials. Ideally, the antibody will help produce a treatment that can help people who have recently been exposed to coronavirus.

“Vaccines have to be given a month or two before infection to provide protection,” McLellan explains. “With antibody therapies, you’re directly giving somebody the protective antibodies and so, immediately after treatment, they should be protected. The antibodies could also be used to treat somebody who is already sick to lessen the severity of the disease.”

The elderly are one of the most at-risk groups when it comes to COVID-19, but older people also don’t typically respond as strongly to vaccines as younger adults. So, a treatment using this antibody may be particularly attractive for older people, as well as healthcare workers who need as much protection as they can get.

So, why llamas? The llama immune system is unique in that produces two different antibodies in response to a threat. The first is very similar to a human antibody, but the second is much smaller and capable of being used in an inhaler.

“That makes them potentially really interesting as a drug for a respiratory pathogen because you’re delivering it right to the site of infection,” says Daniel Wrapp, a graduate student in McLellan’s lab and co-first author of the paper.

If this work does indeed produce a legitimate coronavirus treatment, we’ll all owe a debt of gratitude to Winter, a four-year old llama living in the countryside of Belgium. Her role in all of this started back in 2016 when she was only 9 months old.

At that time, the research team were working on treatment options for earlier coronaviruses (SARS-CoV-1, MERS-CoV). Similar to how humans are given vaccines to develop immunities, Winter was injected with stabilized spike proteins from those coronaviruses

After examining subsequent blood samples from Winter, they noticed a type of antibody that showed the ability to stop coronavirus spike proteins from infiltrating cells.

“That was exciting to me because I’d been working on this for years,” Wrapp notes. “But there wasn’t a big need for a coronavirus treatment then. This was just basic research. Now, this can potentially have some translational implications, too.”

It was this previous work on earlier coronavirus strains that made it possible for the research team to develop this new antibody for SARS-CoV-2 so quickly.

The study is set to be published next week in the journal Cell.

Like studies? Follow us on Facebook!