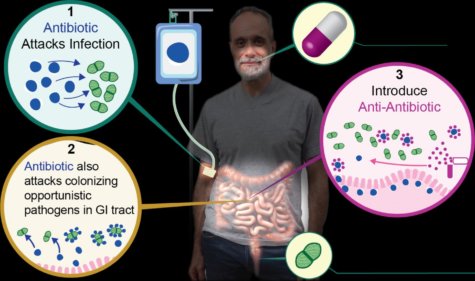

UNIVERSITY PARK, Pa. — Antibiotic resistance is a critical global public health concern. Drug resistant diseases cause nearly a million deaths each year. Scientists have been working for years to develop new treatments that fight disease but don’t cause antibiotic resistance. Now, researchers at Penn State and the University of Michigan may have made a breakthrough. They discovered that a common, inexpensive drug which fights cholesterol can also act as an “anti-antibiotic.” Their study finds the drug allows doctors to prescribe medications without fear of spreading antibiotic resistance.

“Many of our most important antibiotics are failing, and we are beginning to run out of options. We have created a therapy that may help in the fight against antimicrobial resistance, an ‘anti-antibiotic’ that allows antibiotic treatment without driving the evolution and onward transmission of resistance,” says study author and Penn State Professor Andrew Read in a university release.

Read and his colleagues fed mice with a common gut bacteria called E. faecium. They then treated the mice with an antibiotic and determined how much antibiotic resistant E. faecium was in the mice’s feces. They discovered that antibiotic resistance was blocked in mice treated with an antibiotic and the cholesterol-fighting drug cholestyramine.

A cholesterol drug that binds antibiotics

To test their prediction that cholestyramine could prevent antibiotic resistance, the study authors had to prove that treating their mice with antibiotics caused bacteria in their guts to become resistant. They first fed mice the bacterium, which is completely harmless to gut health. Some mice received the antibiotic daptomycin, while others did not. Scientists then collected feces from the mice and searched for antibiotic resistant bacteria. They found plenty.

Next, the team repeated their experiments, but treated some of the mice with both daptomycin and cholestyramine. The results reveal resistant bacteria in the feces of these mice decreased by 80 times the previous amount. They determined that the cholesterol drug bound the antibiotic and prevented it from entering the gut. By preventing a meeting between bug and drug, cholestyramine prevented antibiotic resistance. This means that infections throughout the body can be successfully treated with antibiotics without leading to antibiotic resistance in gut bacteria.

The authors are careful to point out, however, that this study is just the first step. More research is needed to study “anti-antibiotics” like cholestyramine, particularly in humans. Nevertheless, their study is one of the first to bring hope for fighting the antibiotic resistance crisis.

By 2030, health officials estimate antibiotic resistance will put 24 million people into extreme poverty. They add this global health problem also threatens the infrastructure of health care systems and could even undermine the success of cancer treatments.

These findings are published in eLife.