LONDON — Wearing a bicycle helmet can often mean the difference between life and death during an accident. While these helmets go through rigorous testing before use, a new study finds a lot of those safety checks aren’t preparing for the right kinds of injuries. Researchers in London say cycling helmets that claim to protect riders from concussions are actually failing to keep riders safe.

A new method of testing bike headwear has discovered that while newer technologies are reducing brain injury in comparison to older helmets, they are only effective depending on the point of impact. The vast majority of cyclist injuries occur while traveling at speed and their heads hit at an angle that can damage the brain.

Traumatic brain injuries result from a sudden impact or jolt to the head. This can cause bleeding, unconsciousness, memory loss, and mood or personality changes.

Busy roads are a potentially deadly place for bikers

In the United States, safety laws do not require adult cyclists to wear helmets. Some research suggests they can even encourage risk-taking behavior on a bicycle, although helmets generally save more riders from serious injuries.

Researchers have criticized the standard safety test which states cycle helmets must withstand an impact equivalent to an average weight rider travelling at a speed of 12 miles per hour falling onto a curb. This essentially states helmets will help a rider if they topple over as they approach a set of traffic lights, but cannot protect them from being clipped by a passing vehicle at a typical driving speed.

The research team believes, with better method testing, designers could invent a helmet that might actually reduce fatality rates. According to the U.S. National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, just under 900 bicyclists died in traffic crashes in both 2018 and 2019.

“The amount of people cycling since the COVID-19 pandemic began has doubled on weekdays and trebled on weekends in parts of the UK,” says Fady Abayazid from Imperial’s Dyson School of Design Engineering in a university release. “To keep themselves safe, it’s important that cyclists know the best way to protect their heads should they have a fall or collision.”

Bikers don’t have all the facts about their helmets

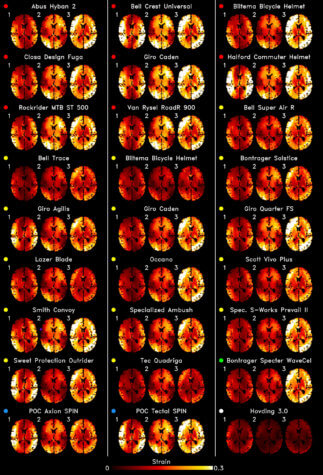

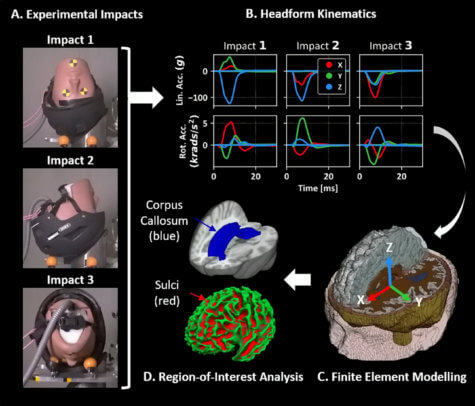

The Imperial College London team compared 27 newer and conventional helmets. Those include ones fitted with airbags, a friction-reducing layer, a shearing pad, and a wavy cellular liner.

At a rig in Sweden, they put the helmets on crash test dummy heads, fitted them with accelerometers and dropped them head-first, side-first, and back-first onto an asphalt substitute at 14 mph. The dummy heads contained sensors that measured and recorded the rotational accelerations experienced during impact, which study authors compared to the human brain.

“Cyclists falling from motion will most often hit the ground at a non-right-angle,” Abayazid continues. “These angles produce rotational forces that subject the brain to twisting and shearing forces – factors contributing to severe TBIs, which can be life-altering.”

“However, current testing standards for bike helmets don’t account for this issue, so we designed a new analysis method to address this gap by combining experimental oblique impacts with a highly detailed computational model of the human brain,” the researcher concludes. “Without a robust, fit-for-purpose testing method and scientific backing, consumers remain underinformed and designers have no specific measures to improve their design decisions.”

The findings appear in the journal Annals of Biomedical Engineering.

SWNS writer Joe Morgan contributed to this report.