NEW ORLEANS — Flame-resistant cotton could be coming to a clothing store near you after scientists figure out how to make the fabric self-extinguish after catching fire. A team from the U.S. Department of Agriculture say the new material is cheaper, safer, and interbreeds two lines of cotton together.

The researchers, from the USDA’s Cotton Chemistry and Utilization Research Unit, note that products derived from the plant range from blue jeans and bedsheets to paper, candles, and even peanut butter. In the U.S. alone, the cotton industry is worth $7 billion a year.

“Textiles made from cotton fibers are flammable and thus often include flame retardant additives for consumer safety,” lead author Dr. Gregory Thyssen and his team writes in the journal PLOS One.

The team’s technique created mutations resulting in superior traits to those of the parents. Screening identified naturally enhanced flame retardant traits in the cotton.

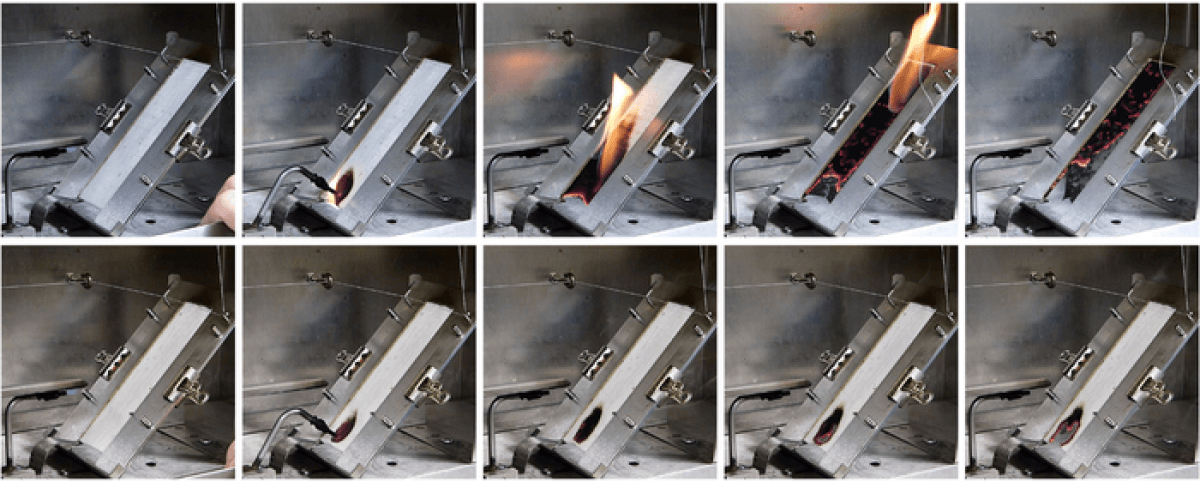

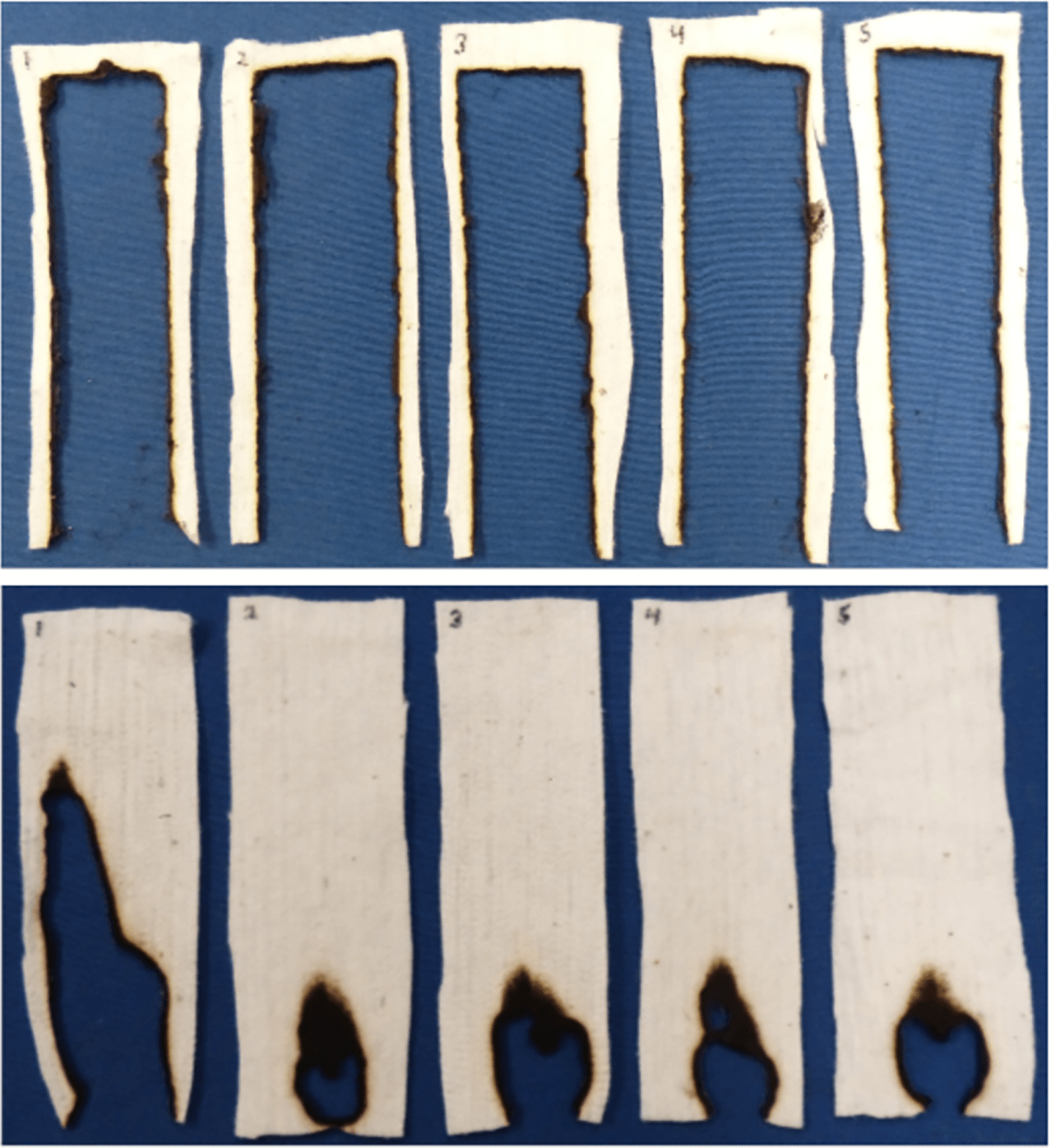

“All eleven parents, like all conventional white fiber cotton cultivars produce flammable fabric,” the researchers report. “Of the textiles fabricated from the five superior RILs, four exhibited the novel characteristic of inherent flame resistance. When exposed to open flame by standard 45° incline flammability testing, these four fabrics self-extinguished.”

Cotton production is very similar worldwide

Cotton plants from fields in India, China, and the U.S. — the world’s top three producers — all grow, flower, and produce cotton fiber very similarly. That’s because they are genetically very similar from country to country.

Breeders select the best-performing plants and crossbreed them to produce better cotton every generation. If one variety produces the best-quality fiber that sells for the best price, growers will plant that type exclusively. However, after many years of this cycle, cultivated cotton all starts to look the same. These plants may be high-yielding and easy for farmers to harvest using machines, but they’re wildly underprepared to fight disease, drought, or insect-borne pathogens.

“Together, these data provide insight into the genetic mechanism of the unexpected emergence of flame-resistant cotton by transgressive segregation in a breeding program. The incorporation of this trait into global cotton germplasm by breeding has the potential to greatly reduce the costs and impacts of flame-retardant chemicals,” researchers write.

Changing cotton on a genetic level

Plants have very large genomes with lots of repetitive sequences, which makes them very challenging to unpack. However, the researchers changed the game for cotton genetics in 2020 by releasing five updated genomes – two cultivated and three wild species.

Having the wild genomes assembled makes it possible to start using their valuable genes to try to improve cultivated varieties of cotton by breeding them together and looking for those genes in their offspring. This approach combines traditional plant breeding with detailed insights into cotton’s genome.

Scientists now know which genes are necessary to make cultivated cotton more resistant to disease, drought, and fire. They also know where to avoid making changes to important agricultural genes.

“Flammability of textiles is an obvious safety and economic concern for textile and cotton consumers, producers and regulatory agencies. Modernizing flame retardant (FR) chemicals has been the focus of research for many years,” the team concludes.

South West News Service writer Mark Waghorn contributed to this report.