STANFORD, Calif. — Heart disease is the leading cause of death in the United States. According to a recent study, death rates due to cardiovascular disease may be linked to certain U.S. counties based on race and ethnicity.

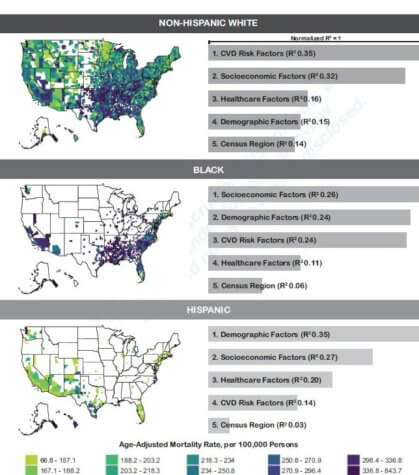

Researchers used CDC data from 2017 to evaluate death rates related to heart disease among each racial and ethnic group, including the counties where these individuals reside. Factors such as population size and the percentage of each ethnic group within that population were taken into account. Also, the region (Northeast, Midwest, South etc.) was noted along with socioeconomic factors like the number of unemployed, poor individuals.

Risks for cardiovascular disease were observed in each population including those with diabetes, those who smoked, and those who were obese and/or who were inactive. Researchers also took note of the ratio of health care providers and the number of adults who were uninsured.

Results indicate that the highest death rate from heart disease is within the Black adult community. They averaged 320 deaths per 100,000 individuals, compared to 168 deaths for the same amount of Hispanic/Latino adults. The study shows that southern states represented the highest death rates related to cardiovascular disease across all ethnic groups.

For the White population, traditional risk factors for heart disease accounted for 35% of related deaths, while poor living and other socioeconomic factors accounted for 26% of the deaths in the Black population. “These results may help develop and implement effective interventions to improve cardiovascular outcomes,” says co-lead study author Dr. Justin Parizo, an advanced heart failure and transplant cardiology fellow at Stanford University, in a statement.

“Currently, population and community-level health interventions are typically focused on disease and medical risk factors, however, our analysis suggests that more emphasis may need to be placed on an intervention that can improve social determinants of health, particularly for Black people,” he continues. “As an example, several trials have shown that income supplementation in addition to nutritional counseling can improve diet among populations at risk for cardiovascular disease. Additionally, interventions to improve housing have been shown to increase patient exercise levels and, in the long term, could decrease unhealthy outcomes such as obesity and Type 2 diabetes.”

Limits of the study include interpretations of the risk factors based on counties, as well as observational research. Findings cannot fully describe each racial group within a population. “For example, a 40% obesity rate among Black people in a county represents the entire Black population but does not necessarily hold true for every subgroup of the Black population,” notes Parizo.

“This study’s greatest value is that it informs the understanding of cardiovascular population health and the numerous factors that play a role in cardiovascular health. Not all populations are the same. A nuanced understanding of the unique influences on cardiovascular outcomes is essential to narrow disparities for various population groups,” said co-senior study author Dr. Fátima Rodriguez, an assistant professor of cardiovascular medicine and a preventive cardiologist and health disparities researcher at the Stanford Prevention Center at Stanford University School of Medicine.

This study is published in the Journal of the American Heart Association.