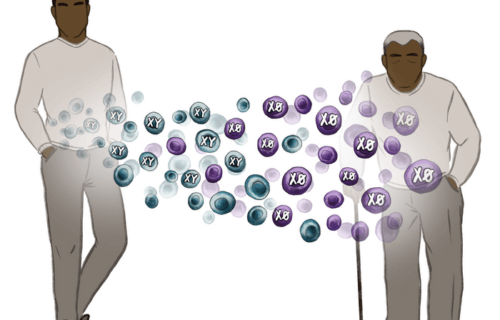

CHARLOTTESVILLE, Va. — Losing the male sex chromosome could be the ticket to an earlier death for many men, a new study finds. Researchers have found that Y chromosome loss is a fairly common occurrence as men age. However, the study finds it also causes the heart muscle to scar — leading to heart failure.

University of Virginia School of Medicine researcher Kenneth Walsh, PhD, estimates that 40 percent of all 70-year-old men lose their Y chromosome. The new findings create even more concern for older men, who already have an average lifespan that’s several years shorter than women.

On average, American women live five years longer than men. Walsh’s team says the discovery that Y chromosome loss leads to heart failure could account for nearly four of those five years.

“Particularly past age 60, men die more rapidly than women. It’s as if they biologically age more quickly,” says Walsh, the director of UVA’s Hematovascular Biology Center, in a university release. “There are more than 160 million males in the United States alone. The years of life lost due to the survival disadvantage of maleness is staggering. This new research provides clues as to why men have shorter lifespans than women.”

Walsh adds that drugs which alleviate organ scarring could be particularly beneficial for men who lose this critical chromosome.

How does a man lose the Y chromosome?

While women are born with two X chromosomes, men have one X and one Y. During the aging process, however, men start to lose the Y in a portion of their cells. Blood cells, which undergo rapid turnover, are particularly vulnerable to this process. On the other hand, male reproductive cells do not lose their Y chromosomes, which is why Y chromosome loss is not a hereditary trait in families.

Study authors say Y chromosome loss is a common problem among smokers. Scientists have found that men who lose this sex chromosome are more likely to die younger and also develop age-related conditions, including Alzheimer’s.

In this new study, researchers from UVA and Uppsala University in Sweden used gene-editing technology to create mice which suffer from Y chromosome loss in the blood. Results show that the animals developed age-related diseases at an accelerated rate. They were also more prone to heart scarring and died at an earlier age.

Study authors note this wasn’t just a case of fatal inflammation. Instead, the mice suffered from a series of immune system reactions which led to fibrosis — a thickening or scarring of the tissue throughout the body.

In humans, the team found Y chromosome loss increased the risk of cardiovascular disease, heart failure, and the risk of premature death.

Are there drugs to prevent this?

Currently, study authors say there’s no easy way of determining which men suffer from Y chromosome loss. Researcher Lars Forsberg from Uppsala University has developed a cheap polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test — just like a COVID test — which can detect Y chromosome loss, but it’s still only available for lab experiments.

“If interest in this continues and it’s shown to have utility in terms of being prognostic for men’s disease and can lead to personalized therapy, maybe this becomes a routine diagnostic test,” Walsh says.

“The DNA of all our cells inevitably accumulate mutations as we age. This includes the loss of the entire Y chromosome within a subset of cells within men. Understanding that the body is a mosaic of acquired mutations provides clues about age-related diseases and the aging process itself,” Walsh concludes. “Studies that examine Y chromosome loss and other acquired mutations have great promise for the development of personalized medicines that are tailored to these specific mutations.”

For now, researchers note that one potential treatment for this problem is pirfenidone, an FDA-approved drug for treating idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, a form of lung scarring.

Scientists are also testing pirfenidone to see if it can help patients with heart failure and chronic kidney disease. Both of those conditions also feature scarring of the organs. The team believes men with Y chromosome loss would respond well to pirfenidone and other antifibrotic drugs, however, more research is still necessary.

The study is published in the journal Science.

Y chromosome loss is the result of years of unhealthy living, eating crap, processed foods, being sedentary and getting fat.

These researchers made mild mention of smoking, but it’s the whole accumulation of bad lifestyle choices which are to blame. Once the damage is done, there is no reversal, so yea, pop pills or whatever. Good luck!

For guys around age 40, get your health together now to reduce the odds of Y chromosome loss in addition to all the other health issues you can surely avoid.

Evidence for your claims?

Deficiencies in Selenium methyl and sulphate groups may cause scarring since cardiomyopathy heart attacks result from low Selenium and MSM and vit K2 are known to reduce scar tissue and remove calcium from blood vessels around the heart. Taking care of these deficiencies may address the loss of the Y chromosome. Until definitive info is available that these deficiencies do not cause the Y chromosome loss it may be safer to assume that the ultimate cause of early death is more likely the result of poor lifestyle nutrition choices generating these deficiencies rather than just isolating the loss of the Y chromosome as the cause. It may be a case of the police always being present at a crime scene does not make them the cause of the crime.

Deficiencies in Selenium methyl and sulphate groups may cause scarring since cardiomyopathy heart attacks result from low Selenium and MSM and vit K2 are known to reduce scar tissue and remove calcium from blood vessels around the heart. Taking care of these deficiencies may address the loss of the Y chromosome. Until definitive info is available that these deficiencies do not cause the Y chromosome loss it may be safer to assume that the ultimate cause of early death is more likely the result of poor lifestyle nutrition choices generating these deficiencies rather than just isolating the loss of the Y chromosome as the cause. It may be a case of the police always being present at a crime scene does not make them the cause of the crime. Further smokers exhaust their vit C levels at the faster rate of 35 mg vit C per cigarette on average and if they do not replace it at levels required to maintain normal serum levels then poor collagen rebuild in the heart muscles may be a result also, hence perhaps the resulting correlation of smoking to Y chromosome loss.