DURHAM, N. C. — Saving money seems so easy for some people. And the key is — you guessed it — patience. So how do these super savers become so patient? Is it all about delayed gratification, or is there a greater discipline involved? Researchers at Duke University discovered some surprising information about what motivates these “patient savers.”

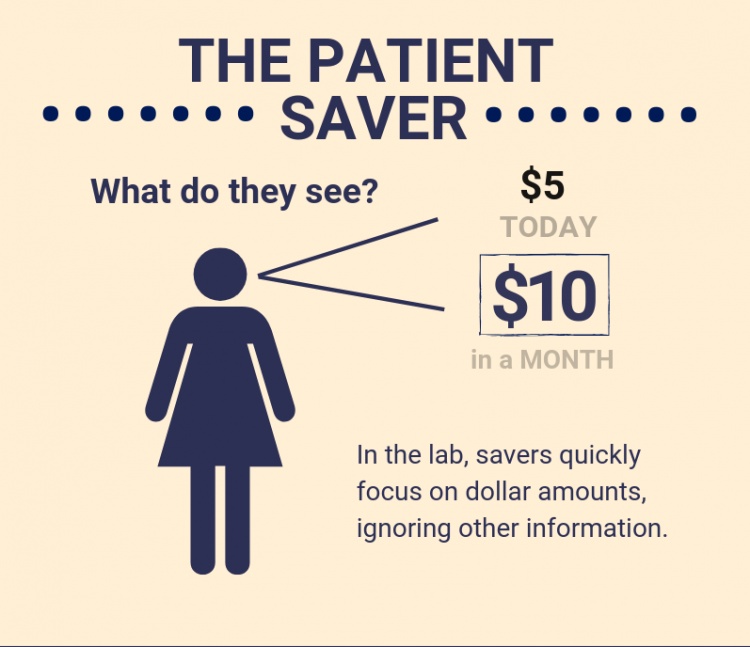

People who seem naturally capable of making sound financial decisions and saving money are not caught up in an internal struggle nor do they possess an iron will that enables them to resist temptation. Instead, they see just two options before them. When faced with a smaller amount of money now or a larger amount of money later, these individuals have an inherent ability to block out all other information.

Researchers studying eye movements of people presented with this very dilemma reveal that a speedy conclusion is reached to aim for the bigger prize by those who are prone to saving.

“Patient people are not doing more analytic work,” says study coauthor Scott Huettel, a psychology professor with the university, in a release. “They actually make these decisions the fastest. It’s the opposite of an effortful process.”

For the study, Huettel and his research team recruited 217 young adults to participate in a task where they were asked to make various monetary decisions. For example, would the participant rather get $5 today or $10 in a month.

While participants were considering their options, researchers tracked their eye movements. The camera system enabled researchers to view the incremental changes in a participant’s focus.

Results showed that natural savers are not working out their choices like pieces in a puzzle. They just toss out all the other considerations, such as the time element, and simply put their entire focus on what matters most to them: the higher dollar amount. Interestingly, the most patient people consider the monetary aspect before thinking about the time element, thus ensuring that they will go for the gold — or in this case the larger amount of cash.

“We can see the savers’ decisions in their eye movements as their eyes jump back and forth between two dollar amounts,” says Huettel. “They don’t integrate information about time and money to determine how much a choice is worth, but instead use a simple rule that helps them make quick but good decisions.”

With savings at historic lows, the authors hope their findings will increase financial literacy and encourage people in ways to make saving money easier.

“Figuring out how people actually make decisions is helpful for pinpointing where the decision process can go awry,” adds co-author Dianna Amasino, a graduate student in neurobiology at the university. “It could give people strategies they can use without having to increase time and effort.”

Researchers also say the results can lead to better strategies and greater motivation for those trying to save money. People must remember to actively focus their energy on the dollar amounts to be gained rather than efforts to resist temptation.

“The way a decision is approached matters,” says Amasino. “Focusing on the long wait to accumulate savings can feel overwhelming. Focusing on the returns to savings and investments can be motivating.”

Findings were published online in the February 2019 edition of Nature Human Behaviour.