CHEVY CHASE, Md. — Does eating an ice cream or drinking a cold beverage bring nothing but agony to your teeth? Now, there’s finally a reason why. Researchers with the Howard Hughes Medical Institute say they’ve uncovered root cause of sensitive teeth.

The nerve jangling condition affects around one in eight adults in the United States. For some, their dental sensitivity to cold can make eating a torturous experience.

“It’s a unique kind of pain. It’s just excruciating,” says study co-author Professor David Clapham in a media release.

Experiments with humans and mice have finally revealed the problem; tooth cells called odontoblasts containing a protein that detects temperature drops. Scientists call this ion channel TRPC5 and it sends signals to the brain which can trigger a stabbing jolt of pain. Luckily, researchers believe toothpastes or drugs that specifically target TRPC5 could end the misery.

“Once you have a molecule to target, there is a possibility of treatment,” explains Professor Katharina Zimmermann from the University of Erlangen-Nuremberg.

Getting to the root of toothaches

The study finds this also explains how an age-old home remedy, clove oil, eases toothaches. Researchers note that the oil contains a chemical that blocks the “cold sensor” protein.

Sensitive teeth, or dentin hypersensitivity, is the most common dental complaint. Along with consuming cold food or liquids, even breathing in cold air can trigger a painful response.

However, pain from sensitive teeth can also occur as a result of receding gums and exposed tooth roots. This can happen when the dentin, the porous part below a tooth’s protective enamel, is left uncovered due to wear and tear.

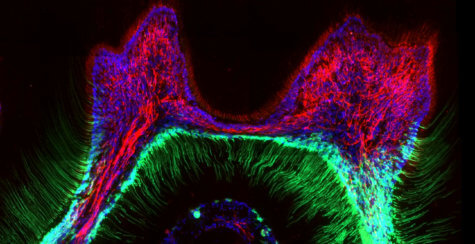

Analysis of human specimens revealed TRPC5 lies between the center pulp of the tooth and the dentin. The “gatekeeper” protein, or ion channel, allows electrical signals to pass in and out. This initiates pangs, twinges, and throbs in the teeth — and amplifies them. When a cold stimulus is applied to the exposed area, a painful sensation occurs.

The wrong bite can go straight to the brain

In mice, recordings of neural activity revealed that an icy solution sparked nerves as teeth sensed the cold. However, this was not the case in peers genetically engineered to lack TRPC5 or treated with a chemical that blocked it.

Prof. Zimmermann says when someone with a dentin-exposed tooth bites down on a popsicle, for example, TRPC5-packed cells pick up on the cold sensation and a signal which says “ow!” shoots to the brain. Study authors add these sharp sensations often get overlooked as a toothache and are not a “trendy” area of science for many researchers.

“It is important and it affects a lot of people,” Prof. Clapham contends.

The study notes that roughly a third of the world’s population, 2.4 billion people, have untreated cavities. They can cause intense suffering and add to extreme cold sensitivity in the teeth.

The study, appearing in the journal Science Advances, is the culmination of more than a decade of work. Prof. Zimmermann says figuring out the function of particular cells is difficult, “and good research can take a long time.”

SWNS writer Mark Waghorn contributed to this report.