BOULDER, Colo. — What was the weather like thousands of years ago? Scientists now have a better idea after mapping summers and winters on Earth — for the last 11,000 years!

The ambitious project sheds fresh light on climate change. It is the very first seasonal temperature record of its kind from anywhere in the world. The findings in the journal Nature are based on ice cores drilled out of the Antarctic.

“The goal of the research team was to push the boundaries of what is possible with past climate interpretations, and for us that meant trying to understand climate at the shortest timescales, in this case seasonally, from summer to winter, year-by-year, for many thousands of years,” says study lead author Tyler Jones, an assistant research professor and fellow at the Institute of Arctic and Alpine Research (INSTAAR), in a university release.

The results date back to the beginning of what is known as the Holocene, when woolly mammoths roamed the tundra of Europe and North America. This study also validates a weather phenomenon dubbed “Milankovitch cycles” — explaining the response of seasonal temperatures in polar regions.

Serbian scientist Milutin Milankovitch claimed a century ago that changes in Earth’s position relative to the Sun — due to slow variations of its orbit and axis — are a strong driver of ice ages irrespective of human influence.

“I am particularly excited that our result confirms a fundamental prediction of the theory used to explain Earth’s ice-age climate cycles: that the intensity of sunlight controls summertime temperatures in the polar regions, and thus melt of ice, too,” says Kurt Cuffey, a co-author on the study and professor at UC Berkeley.

Earth’s climate history is trapped in ice

The highly detailed data on long-term climate patterns of the past also have important implications for impacts of greenhouse gas emissions today. Planetary cycles help identify the human influence on climate change and its effect on global temperatures.

“This research is something that humans can really relate to because we partly experience the world through the changing seasons—documenting how summer and winter temperature varied through time translates to how we understand climate,” says Jones.

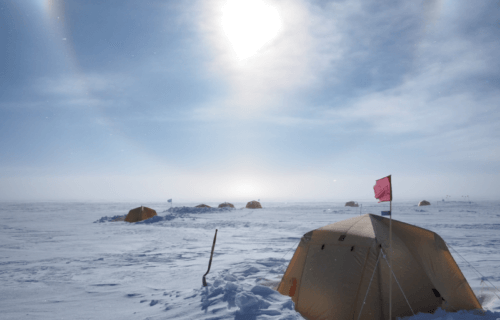

Slender, cylindrical columns of ice drilled from ancient ice sheets in Antarctica and Greenland open a window into past atmospheric concentrations of greenhouse gases and past temperatures of the air and oceans.

They are cut into small sections and safely transported to academic institutions, such as the Stable Isotope Lab in Colorado. The longest is the West Antarctic Ice Sheet (WAIS) Divide, measuring over two miles (11,171 feet). Nearly five inches wide, it contains information that dates back roughly 68,000 years.

Dr. Jones and colleagues analyzed a continuous record of water-isotope ratios from WAIS. It revealed transitions between ice ages and warm periods in Earth’s past. The team used extremely high-resolution measurements and advances in ice core analysis from the past 15 years.

“Even beyond that, we had to develop new methods entirely to deal with this data, because no one’s ever seen it before. We had to go above and beyond what anyone’s done in the past,” Jones adds.

‘This is going to be a really big deal’

For more than three decades, the researchers have been studying a variety of stable isotopes. The non-radioactive forms of atoms with unique molecular signatures are found everywhere from the inside ice cores and the carbon in permafrost to the air in our atmosphere.

“I have this distinct memory of walking into my advisor, Jim White’s office in about 2013, and showing him that we would be able to pull out summer and winter values in this record for the last 11,000 years—which is extremely rare. In our understanding, no one had ever done this before,” Jones explains. “We looked at each other and said, ‘Wow, this is going to be a really big deal.’”

It then took almost a decade to figure out the proper way to interpret the data, from ice cores drilled many years before that meeting. The next step is to attempt to interpret high-resolution ice cores in other places, such as the South Pole and in northeast Greenland, where cores have already been drilled, to better understand our planet’s climate variability.

“Humans have a fundamental curiosity about how the world works and what has happened in the past, because that can also inform our understanding of what could happen in the future,” Jones concludes.

South West News Service writer Mark Waghorn contributed to this report.

Even though the research is valid let’s not stir up the climate psychos any more than they already are.

If one does not learn from the past, one is bound to repeat it!

If one does not learn from the past, one is bound to repeat it!