RALEIGH, N.C. — Just like Earth, Venus is geologically active, according to new research. The fiery second planet from the Sun has a plate tectonic-style system, which sheds fresh light on the mysterious geology of the planet.

Venus has a similar size and mass to Earth and is made of the same stuff. The hellish world may even have harbored life two billion years ago.

“We’ve identified a previously unrecognized pattern of tectonic deformation on Venus,” says study lead author Professor Paul Byrne of North Carolina State University, in a statement. “It’s driven by interior motion — just like on Earth. Although different from the tectonics we currently see on Earth it’s still evidence of interior motion being expressed at the planet’s surface.”

Crustal blocks jostle against each other like broken chunks of pack ice, shining a fresh light on tectonics on Earth and elsewhere. Venus was long assumed to be a “dead” planet, but continental collisions provide nutrients essential for life and could help identify habitable planets outside the solar system.

Venus was thought to have an immobile solid outer shell, or lithosphere, just like barren Mars and Earth’s moon. In contrast, Earth’s lithosphere is broken into tectonic plates that slide against, apart from, and underneath each other on top of a hot, weaker mantle layer.

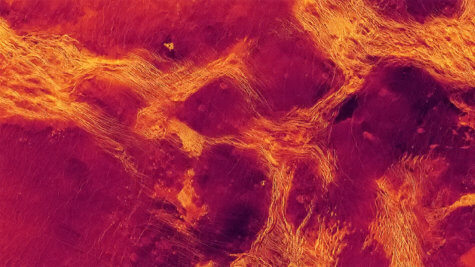

The study is based on radar images from NASA’s Magellan mission to map the surface of Venus. Researchers analyzed the extensive Venusian lowlands that make up most of the planet’s surface.

There were areas where large blocks of the lithosphere seem to have moved. They have been pulled apart and pushed together and have also rotated and slid past each other “like broken pack ice over a frozen lake,” explains the research team. A computer model of the deformation found that sluggish motion of the planet’s interior can account for the style of tectonics seen at the surface.

“These observations tell us that interior motion is driving surface deformation on Venus, in a similar way to what happens on Earth. Plate tectonics on Earth are driven by convection in the mantle. The mantle is hot or cold in different places, it moves, and some of that motion transfers to Earth’s surface in the form of plate movement,” says Prof. Byrne. “A variation on that theme seems to be playing out on Venus as well. It’s not plate tectonics like on Earth — there aren’t huge mountain ranges being created here, or giant subduction systems. But it is evidence of deformation due to interior mantle flow, which hasn’t been demonstrated on a global scale before.”

The patterns linked to the crustal blocks suggest Venus is still geologically active. “We know that much of Venus has been volcanically resurfaced over time, so some parts of the planet might be really young, geologically speaking,” adds Byrne. “But several of the jostling blocks have formed in and deformed these young lava plains, which means that the lithosphere fragmented after those plains were laid down. This gives us reason to think that some of these blocks may have moved geologically very recently — perhaps even up to today.”

The researchers hope Venus’ “pack ice” pattern will offer clues to understanding tectonic deformation on planets outside of the solar system, as well as on a much younger Earth. “The thickness of a planet’s lithosphere depends mainly upon how hot it is, both in the interior and on the surface. Heat flow from the young Earth’s interior was up to three times greater than it is now, so its lithosphere may have been similar to what we see on Venus today: not thick enough to form plates that subduct, but thick enough to have fragmented into blocks that pushed, pulled, and jostled,” says Prof. Byrne.

NASA and the European Space Agency recently approved three new spacecraft missions to Venus that will acquire observations of the planet’s surface at much higher resolution than Magellan. “It’s great to see renewed interest in the exploration of Venus, and I’m particularly excited that these missions will be able to test our key finding that the planet’s lowlands have fragmented into jostling crustal blocks,” Prof. Byrne said.

Venus is the hottest planet in the solar system, with a surface temperature of 932 degrees Fahrenheit — high enough to melt lead. It may have harbored oceans for a billion years of its history. There is even a region of the planet’s thick atmosphere where microbial life could survive, floating among the clouds.

SWNS writer Mark Waghorn contributed to this report.