SAN DIEGO, Calif. — A device that uses tiny worms to “sniff out” lung cancer could help save lives by detecting the disease before it spreads. Researchers in Korea say the worms are drawn to the “floral” smell of cancer cells — which likely resembles their favorite food.

According to the National Cancer Institute, over 600,000 people in the United States died of cancer in 2020. However, when doctors diagnose the disease early – in stage one – before it spreads to other parts of the body, patients have a much higher chance of survival.

Currently, lung cancer is diagnosed by imaging tests or biopsies, but these tests cannot detect tumors at their earliest stage. While scientists can train dogs to sniff out cancer in human breath, blood, and urine samples, keeping them in a medical lab is not practical.

The team from Myongji University in Korea enlisted the help of a much smaller creature, a worm called C. elegans, which can also detect the disease.

“Lung cancer cells produce a different set of odor molecules than normal cells,” says lead study author Dr. Shin Choi in a media release.

“It’s well known that the soil-dwelling nematode, C. elegans, is attracted or repelled by certain odors, so we came up with an idea that the roundworm could be used to detect lung cancer.”

Worms can pick up cancer’s scent with high accuracy

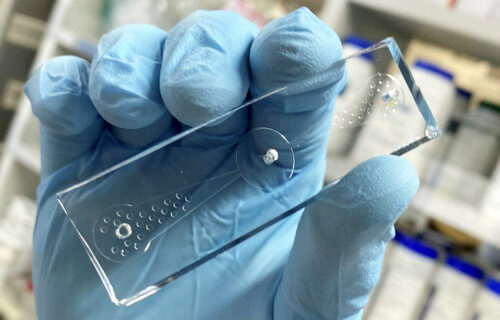

During their experiment, researchers placed a silicone chip, with wells on both ends, connected to a central chamber by channels in a petri dish. They then added a solution containing lung cancer cells at one end of the chip and normal cells at the other.

Worms in the central chamber were more likely to move towards the lung cancer cells, the study finds. Based on their results, the device had a success rate of around 70 percent in terms of detecting cancerous cells. Further tests with the chip revealed what specific odor molecules attracted the worms to the cancer cells.

The team discovered that the worms were attracted to a volatile compound known as 2-ethyl-1-hexanol, which gives off a floral scent.

“We don’t know why C. elegans are attracted to lung cancer tissues or 2-ethyl-1-hexanol, but we guess that the odors are similar to the scents from their favorite foods,” says graduate student and study author Nari Jang.

The researchers are now hoping to increase the device’s accuracy by using worms which have already been exposed to cancer cells and therefore know what they smell like. Once perfected, the researchers are hoping to extend their testing on urine, saliva, and even the breath from cancer patients.

“We will collaborate with medical doctors to find out whether our methods can detect lung cancer in patients at an early stage,” Choi concludes.

Researchers are presenting their findings at the spring meeting of the American Chemical Society (ACS).

South West News Service writer Tom Campbell contributed to this report.