PROVIDENCE, R.I. — Brain surgery may have been a medical procedure the rich and famous had access to in the Middle East over 3,500 years ago, a new study reveals. Archaeologists from Brown University have uncovered evidence of a surgical procedure called trephination in what is now modern-day Israel around 1500 B.C.

Trephination — also known as trepanning, trepanation, or burr holing — involves drilling a hole in the skull. A recent excavation in the ancient city of Megiddo unearthed the earliest example of trephination as well as one of the oldest potential examples of leprosy in the world.

Archaeologists know that people have been practicing cranial trephination for thousands of years. They’ve discovered evidence of this among ancient civilizations in South America, Africa, and elsewhere. Now, there’s new evidence that one particular type of trephination dates back to at least the late Bronze Age.

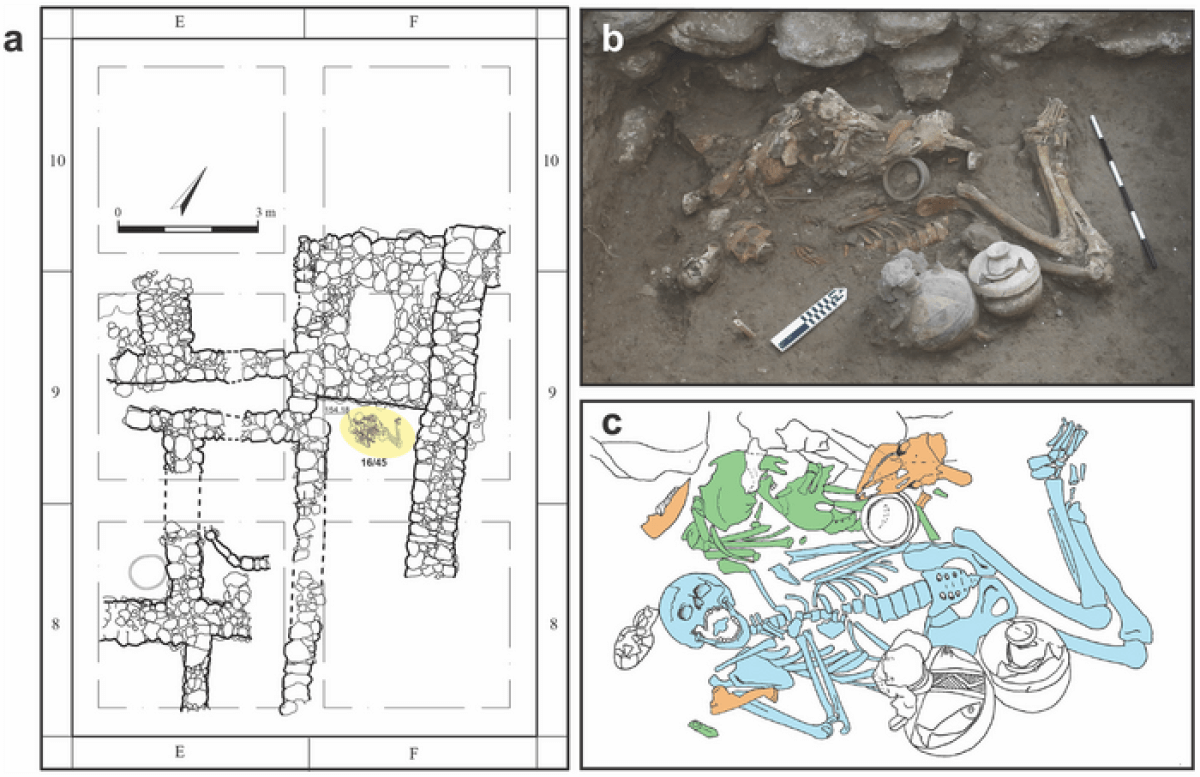

The research team notes that two “high status” brothers buried in the same tomb were severely ill. However, the family apparently had access to rare treatments during that age. Study authors examined their remains, which were buried beneath an “elite” residence at an archaeological site at Tel Megiddo — the site of the ancient city of Megiddo.

DNA testing suggests the buried individuals were brothers. Both skeletons show evidence of disease. The researchers add that extensive lesions on the bones of both men point to a chronic and debilitating illness. It’s also possible that the condition was something the brothers shared a vulnerability to genetically.

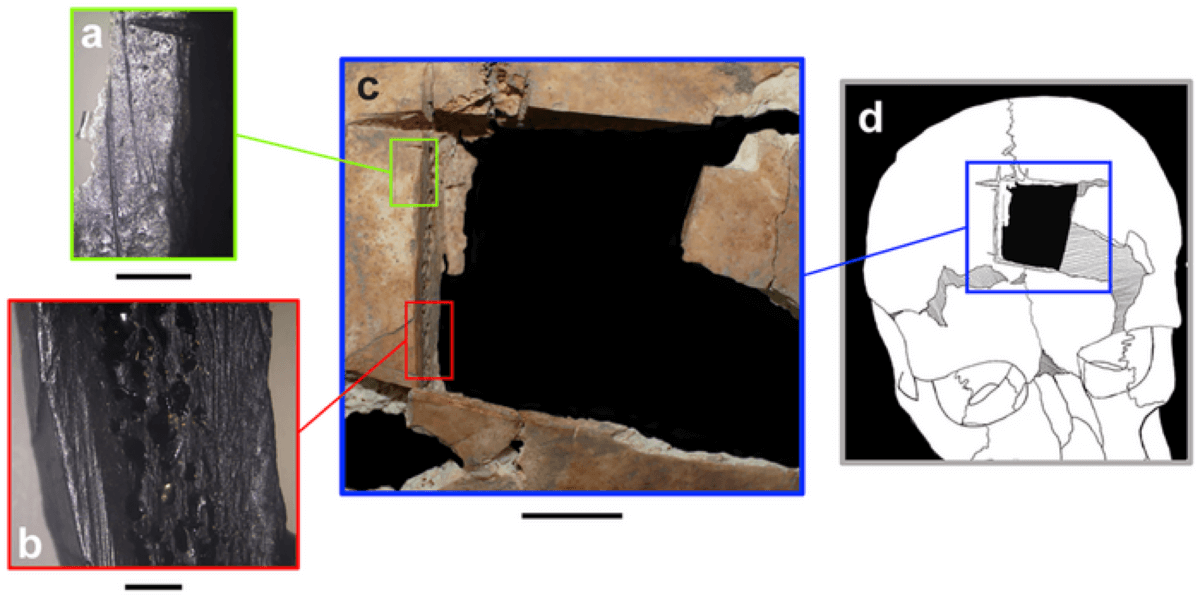

Rachel Kalisher, a Ph.D. candidate at Brown University, led the analysis of the excavated remains. She found that not long before one of the brothers died, he underwent angular notched trephination. The procedure involves cutting the scalp open, using an instrument with a sharp beveled edge to carve four intersecting lines in the skull, and using leverage to make a square-shaped hole in the bone.

Kalisher says the advanced state of the lesions suggests that the men survived for many years, despite the severity of their illness. This also points to the family’s wealth and status giving them more opportunities to try new treatments — like brain surgery.

The researchers report that one of the men had a 30-millimeter square hole in the frontal bone of the skull that was surgically removed. In modern times, surgeons use trephination to treat various medical disorders by relieving pressure in the skull.

Although ancient surgeons likely tried to treat the patient’s ailment during this procedure, study authors say the lack of bone healing suggests the patient died during or shortly after the surgery.

The team also notes that the brothers’ tomb was adorned with high quality food and fine ceramics, similar to other nearby high-status tombs. This suggests these men were not excluded from normal burial traditions due to their poor health. Kalisher adds the trephination is the earliest example of its kind discovered in the region.

“We have evidence that trephination has been this universal, widespread type of surgery for thousands of years,” Kalisher says in a university release.

“But in the Near East, we don’t see it so often — there are only about a dozen examples of trephination in this entire region. My hope is that adding more examples to the scholarly record will deepen our field’s understanding of medical care and cultural dynamics in ancient cities in this area.”

Kalisher reports that the bones she analyzed came from a domestic area directly adjacent to Megiddo’s late Bronze Age palace. This suggests that the pair were leading members of society and possibly even royals themselves.

“These brothers were obviously living with some pretty intense pathological circumstances that, in this time, would have been tough to endure without wealth and status,” Kalisher explains. “If you’re elite, maybe you don’t have to work as much. If you’re elite, maybe you can eat a special diet. If you’re elite, maybe you’re able to survive a severe illness longer because you have access to care.”

The study authors note that both brothers died young, one in his teens or early 20s and the other sometime between his 20s and 40s. They both likely succumbed to an infectious disease. A third of one brother’s skeleton, and half of the other brother’s, shows porosity, lesions, and signs of inflammation in the membrane covering the bones. Based on those findings the team believes the pair had systemic and sustained cases of an infectious disease such as tuberculosis or leprosy. Kalisher says that while some skeletal evidence points to leprosy, it’s tough to diagnose it using ancient bones alone.

“Leprosy can spread within family units, not just because of the close proximity but also because your susceptibility to the disease is influenced by your genetic landscape,” the researcher continues. “At the same time, leprosy is hard to identify because it affects the bones in stages, which might not happen in the same order or with the same severity for everyone. It’s hard for us to say for sure whether these brothers had leprosy or some other infectious disease.”

Researchers say that if ancient surgeons meant to keep the brothers alive using angular notched trephination, it didn’t work. The patient may have died minutes after the procedure.

“You have to be in a pretty dire place to have a hole cut in your head,” Kalisher notes. “I’m interested in what we can learn from looking across the scientific literature at every example of trephination in antiquity, comparing and contrasting the circumstances of each person who had the surgery done.”

“In antiquity, there was a lot more tolerance and a lot more care than people might think,” Kalisher concludes. “We have evidence literally from the time of Neanderthals that people have provided care for one another, even in challenging circumstances. I’m not trying to say it was all kumbaya — there were sex- and class-based divisions. But in the past, people were still people.”

The findings are published in the journal PLoS ONE.

South West News Service writer Stephen Beech contributed to this report.