RIVERSIDE, Calif. — Younger generations often get a reputation for having shrinking attention spans, but new research suggests its actually older adults who are more easily distracted. Scientists at the University of California-Riverside report that while engaging in a particularly high-effort physical task, such as driving a car or carrying groceries, older adults are more likely than their younger counterparts to be distracted by items irrelevant to the task at hand.

Study authors assessed the interaction between physical exertion and short-term memory performance among younger and older adults — when distractors were either present or absent.

“Action and cognition, which interact often in daily life, are sensitive to the effects of aging,” says graduate student and first study author Lilian Azer, in a university release. “Our study found that in comparison to younger adults, older adults are less likely to ignore distractors in their surroundings when simultaneously engaging in a cognitive task and an effortful physical task. Ignoring task-irrelevant items declines with age and this decline is greater when simultaneously performing a physical task — a frequent occurrence in daily life.”

According to Azer, these age-related differences amplify during situations in which the demands on a person are higher. More specifically, the risk for distraction grows under increased physical exertion or in the presence of more nearby distractors.

The research team analyzed what impact a simple physical action would have on working memory and inhibitory control. Working memory, also known as short-term memory, is a core cognitive process for maintaining information while engaging in other, ongoing mental activities. Inhibitory control, meanwhile, is the capacity to ignore distracting information irrelevant to a task while focusing on task-relevant information.

To research these topics, study authors gathered 19 older adults, between 65 and 86 years-old, from local communities in Riverside, California for the two-year project. The team also recruited an additional 31 younger adults (ages 18-28) from UC Riverside psychology undergraduate courses in exchange for course credit.

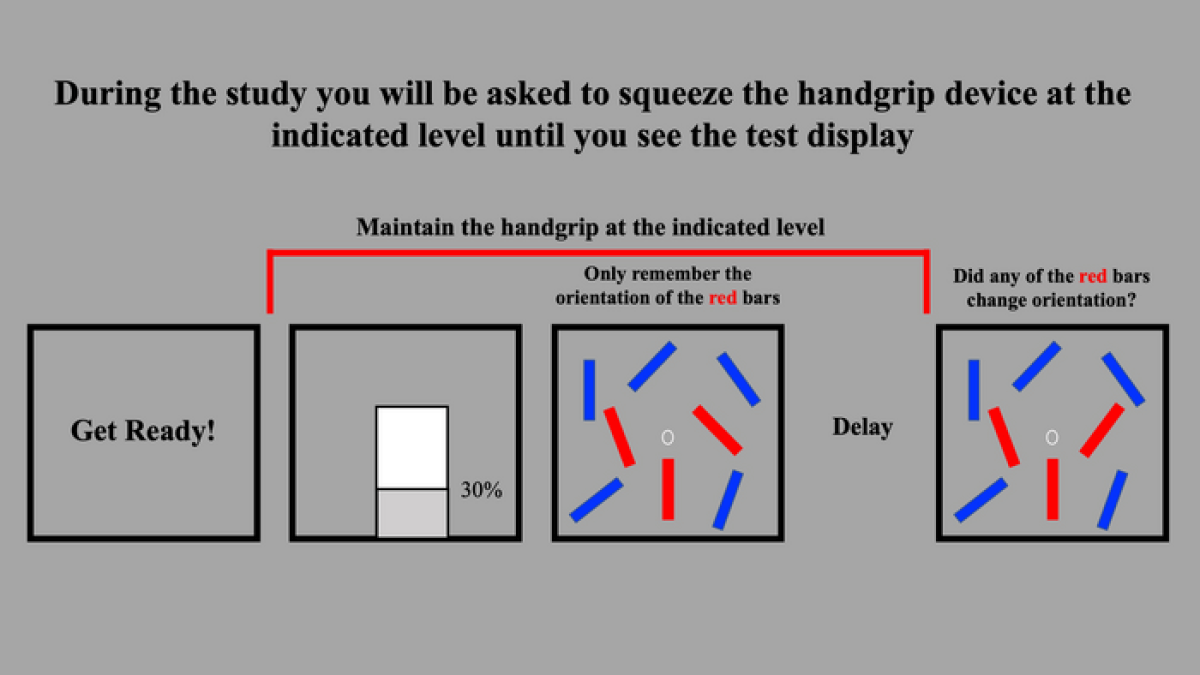

Each person had to grip a hand dynamometer, a kind of handgrip device, at either five or 30 percent of their strength while performing a short-term memory task. While that was happening, a centrally located visual gauge provided researchers with real-time feedback on the exerted grip force, and a nearby memory array featured small blue and red orientation bars. Participants’ grip was of the variety used while carrying a grocery bag, walking up a stairwell, or driving.

The participants had to focus on the red bars, and the blue bars served as distractions, mimicking everyday distractions such as a vibrant billboard, a car honking, or an unrelated conversation. During exercises featuring no distractors, the group viewed three red bars momentarily and then had to remember the bars’ orientation later on. When the test incorporated distractors into the experiment, participants saw five blue bars as well, but they had to only remember the orientation of the red ones.

“We found that under high physical effort older adults were less likely to both ignore the distracting information and focus on the task-relevant information,” Azer reports. “Our results suggest that older adults might have heightened distractibility.”

The country’s senior population is about to skyrocket

Estimate project that by 2030 older Americans will make up roughly 21 percent of the U.S. population — a notable increase from 15 percent in 2018. By 2060, close to 25 percent of Americans will be 65 and older.

Weiwei Zhang, who led the study, stresses the importance of understanding age-related declines in both physical and mental functions along with their interactions. He explains that as people grow older, they may experience a reduction in muscle mass and strength, as well as declines in key cognitive processes (worse short-term memory, slower speed of processing information, and heightened distractibility).

“It is important to understand that as we grow older, we may be more prone to distractors and this may be amplified during instances of simultaneous effortful physical action,” notes Zhang, an associate professor of psychology and a member of UCR’s Aging Initiative. “Understanding how cognitive and physical actions interact can help us be more aware of how distracting information in our environment may impair our working memory.”

– stock.adobe.com)

You might also be interested in:

- Deep sleep can protect older adults from Alzheimer’s-related memory loss

- Omega-3 fatty acids from fish can improve attention span, impulsivity in children

- Nearly 100% of motorists have driven distracted — 1 in 3 incidents lead to a crash, survey finds

A decline in one’s ability to ignore distractors as they grow older is a result of normal cognitive aging, researchers say. The prefrontal cortex, a part of the cerebral cortex involved with remote memory consolidation, plays a role, and is usually involved in working memory and inhibitory control.

According to Azer, effortful mental or physical activities are key to everyday functioning. For instance, when we drive, we tend to hold the steering wheel with about 30 percent of our maximum physical strength, and carrying heavy shopping bags usually uses about 20 percent of our maximum physical strength.

“As we engage in these physical activities, very often we simultaneously engage in cognitive tasks where distractors — a billboard or a car sales commercial on the radio — may be present,” Azer explains. “Inhibitory control may suffer during these concurrent tasks, making it more difficult, especially for older adults, to ignore the distractors and focus on task-relevant information. Since it is rare that we perform a physical or cognitive task in complete isolation, it is important to minimize distractions. If this is not possible, we need to be aware that the effortful physical task may impair our ability to both perform a working memory task and successfully ignore surrounding distracting information.”

Moving forward, the research team is planning on conducting further experiments investigating the impact of effortful physical action on cognitive function.

“We would like to understand the role of arousal induced by physical effort and how this arousal can impact response time and inhibitory control,” Azer concludes.

The study is published in the journal Psychology and Aging.