GRONINGEN, Netherlands — There are still many unanswered questions about the world in biblical times. While many find their answers in faith, science is shedding fresh light on one of the most famous ancient texts. Researchers at the University of Groningen are using artificial intelligence to crack the code of the Dead Sea Scrolls.

Using computer algorithms, scientists have identified the writing of two different individuals, possibly revealing the origins of the scrolls. The priceless manuscripts were discovered more than 70 years ago in seaside caves near the ancient settlement of Qumran.

They provide a link to The Bible’s past however, the scribes who created them did not sign their work. Until now, scholars have said the handwriting points to the scrolls being the work of a single person.

“They would try to find a ‘smoking gun’ in the handwriting, for example, a very specific trait in a letter which would identify a scribe,” says study leader and theologist Professor Mladen Popović in a university release.

Popović adds this line of thinking is somewhat subjective and often leads to fierce debates.

AI breaks down the handwriting in the scrolls

In this study, researchers used computer learning to analyze biomechanical traits, like the way someone holds a pen or stylus. They focused on the Great Isaiah Scroll, the best preserved of all 900 pieces of parchment or papyrus. It contains a Hebrew version of the book of Isaiah.

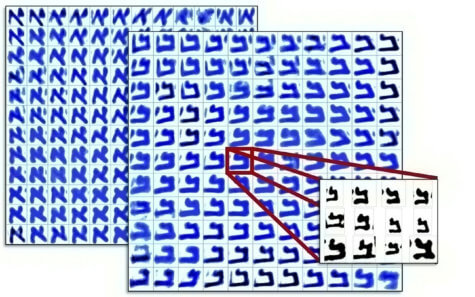

“This scroll contains the letter aleph, or ‘a’, at least five thousand times. It is impossible to compare them all just by eye,” explains co-author Prof. Lambert Schomaker, an AI expert at Groningen.

Digital imaging enabled the team to analyze each curve of the characters at the microscopic level and as a whole.

“The human eye is amazing and presumably takes these levels into account too. This allows experts to ‘see’ the hands of different authors, but that decision is often not reached by a transparent process,” Popović says. “Furthermore, it is virtually impossible for these experts to process the large amounts of data the scrolls provide.”

How many people created the scrolls?

The conventional wisdom is a mysterious Jewish sect, the Essenes, created the scrolls. Historians believe the Essenes occupied Qumran during the first centuries BC and AD. However, others say they originated elsewhere and were written by multiple groups; some fleeing the Roman siege that destroyed the legendary Temple in Jerusalem around 70 AD.

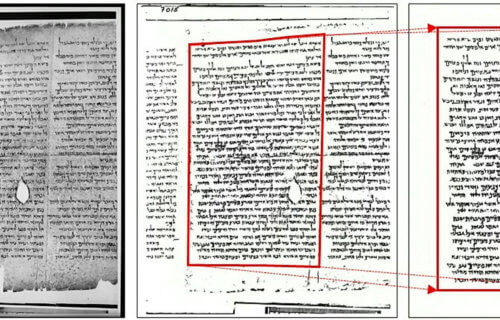

An algorithm separated the text from its background leather or papyrus. The neural network then kept the original traces made by the scribe more than 2,000 years ago intact.

“This is important because the ancient ink traces relate directly to a person’s muscle movement and are person-specific,” Prof. Schomaker adds.

The features reveal the 54 columns fell into two different groups that were not distributed randomly. Instead, they were clustered with a transition around the halfway mark. The patterns of letter fragments confirm the presence of two different writers.

“When we added extra noise to the data, the result didn’t change. We also succeeded in demonstrating that the second scribe shows more variation within his writing than the first, although their writing is very similar,” Prof. Schomaker reports.

Turning the heat up on history

Researchers then turned to heat maps to produce an average version of ‘aleph’ or ‘a’ for the first 27 columns and the last 27 columns. When study authors compared these two average letters by eye they could see the difference. This links the computerized and statistical analysis to human interpretation of the information. Certain aspects led some scholars to suggest after column 27, a new scribe took over. However, this theory is not generally accepted.

“Now, we can confirm this with a quantitative analysis of the handwriting as well as with robust statistical analyses. Instead of basing judgment on more-or-less impressionistic evidence, with the intelligent assistance of the computer we can demonstrate that the separation is statistically significant,” Popović declares.

The study, appearing in PLOS ONE, opens the door to analyzing the scrolls based on its physical characteristics. Now, researchers can access the microlevel of individual scribes and carefully observe how they worked on these manuscripts.

“This is very exciting, because this opens a new window on the ancient world that can reveal much more intricate connections between the scribes that produced the scrolls. In this study, we found evidence for a very similar writing style shared by the two Great Isaiah Scroll scribes, which suggests a common training or origin. Our next step is to investigate other scrolls, where we may find different origins or training for the scribes,” Popović says.

In this way, it will be possible to learn more about the communities that may have produced the Dead Sea Scrolls.

“We are now able to identify different scribes,” the study leader concludes. “We will never know their names. But after seventy years of study, this feels as if we can finally shake hands with them through their handwriting.”

SWNS writer Mark Waghorn contributed to this report.