LAUSANNE, Switzerland — The number of births plunged during the coronavirus pandemic, and researchers in Europe say social distancing and lockdowns are to blame.

The study finds couples were having less sex due to lockdown measures, with the United Kingdom among the countries feeling the biggest impact. Births were down by 13 percent in England and Wales, and 14 percent in Scotland. This could have “long term consequences” for aging populations.

“The decline in births nine months after the start of the pandemic appears to be more common in countries where health systems were struggling and capacity in hospitals was exceeded. This led to lockdowns and social distancing measures to try to contain the pandemic,” says first author of the study, Dr. Léo Pomar, a midwife sonographer at Lausanne University Hospital and associate professor at the School of Health Sciences in Lausanne, in a media release.

“The longer the lockdowns the fewer pregnancies occurred in this period, even in countries not severely affected by the pandemic. We think that couples’ fears of a health and social crisis at the time of the first wave of COVID-19 contributed to the decrease in live births nine months later.”

How much is the birth rate dropping?

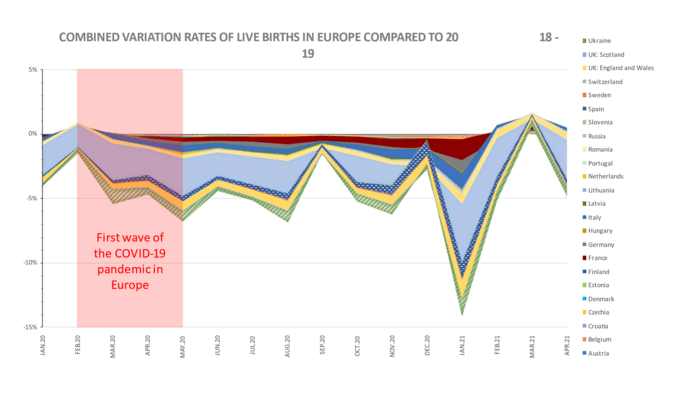

The Swiss team analyzed data from 24 European countries covering periods immediately before and after the first wave of COVID-19. Overall, the drop in newborns was 14 percent in January 2021, nine to 10 months after the first virus peaks and lockdowns.

This was compared to averages in January 2018 and 2019. However, births went up in March 2021, the only month with a live birth rate similar to the pre-pandemic rate. This period corresponded to a rebound nine to 10 months after the end of lockdowns, but it did not compensate for the decline in January 2021.

Problems such as infections, deaths, miscarriages, or still births were ruled out as the potential cause by the researchers. There would have been a drop just a few weeks or months after exposure to the coronavirus, which was not the case. Lockdowns were identified as the only factor.

“The association we found with the duration of lockdowns may reflect a much more complex phenomenon, in that lockdowns are government decisions used as a last resort to contain a pandemic. Lockdown duration has a direct impact on couples,” Dr. Pomar reports.

(CREDIT: Human Reproduction)

Did overcrowded hospitals play a role?

Seven countries had intensive care units that were “over occupied” — more than 100 percent full. Six of these nations saw substantial decreases in birth rates. The findings are important for health services and policy makers.

“It is of particular importance for maternity services, which could adapt staffing levels to birth patterns after pandemics: fewer pregnancies are expected at the time of pandemics, but a rebound in pregnancies could be observed after the end of them. The fact that the rebound in births does not seem to compensate for the decrease in January 2021 could have long-term consequences on demographics, particularly in western Europe where there are aging populations,” the researcher says.

Adjusting for seasonal variations showed this was the only month in which there was a significant drop. At a national level, the biggest decrease was in Lithuania (28%), followed by Ukraine (24%), Spain (23.5%), Romania (23%), Russia (19%), Portugal (18%), and Italy (17%). Then came Latvia (15.5%), Scotland and France (14% each), England, Wales, and Estonia (13%), and Belgium (12%).

Only two out of nine countries in which there was a slight or moderate impact on intensive care units experienced a decline in births nine months later. Dr. Pomar and colleagues are now planning to see if there are similar trends after subsequent lockdowns.

“Over time, the pandemic becomes endemic, its consequences during pregnancy are better known, vaccination is available, and it is possible that this decline in births has been mitigated in subsequent waves,” Pomar continues.

How does this compare to other epidemics?

The 1918 Spanish flu pandemic and the 2013 Ebola and 2016 Zika virus outbreaks were also linked with a decline in birth rates. The reasons were high death rates among parents for the first two and deaths among fetuses as a result of direct exposure to Zika, although postponing pregnancy also played a role.

“These observations are important because they show that human reproductive behavior, as evidenced by numbers of live births, changes during dramatic events, epidemics and global crises,” says Professor Christian De Geyter from the University of Basel, who did not take part in the study.

“Fewer live births will result in more rapidly aging populations and in lesser economic growth. Some rebound of the live birth numbers after each of these crises may mitigate these constraints, but sequential multiple crises may also result in live birth numbers not recovering.”

“People are now aware that profound stressors during pregnancy may affect placental function, neonatal health and even future fertility… Undulating fertility aspirations caused by crises will invariably affect fertility treatment; furthermore, temporal fluctuations in live birth numbers will impact on the strain on obstetrical care units, schooling facilities and, ultimately, national socioeconomic stability.”

The study is published in the journal Human Reproduction.

South West News Service writer Mark Waghorn contributed to this report.