DURHAM, N.C. — The spread of Chlamydia, a common sexually transmitted disease, is fueled by the virus world’s version of Harry Potter’s invisibility cloak, a new study reveals.

It helps the infection dodge the body’s immune system and hide undetected inside host cells, according to researchers at Duke University. The “cloaking device” contains a veil of microbes. Now, scientists have identified this mechanism and intend to pull it apart.

“We knew there was the potential to kill Chlamydia, but when we did experiments with the human-adapted form, Chlamydia trachomatis, it was very good at growing in human cell cultures,” says lead author Professor Jorn Coers of Duke University in a media release.

The Duke team used an immune stimulant to alert the cell’s defense systems to its presence, but nothing happened.

“We said, there’s the pathogen. Our defense system should see it. Why does it not see it?” Coers explains.

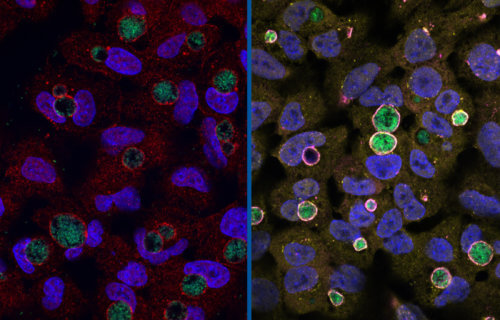

They found a gene called GarD (gamma resistance determinant) that blocks cells from “marking” a Chlamydia infection for attack. Mutating the protein left the bacteria vulnerable to destruction. Prof. Coers says GarD is the stealth factor protecting the STD.

How does this cloak work?

It interferes with the ability of an enzyme called mysterin (RNF213) to sense small bits of bacterial molecules poking out of the shell of the storage vessel, or inclusion.

“RNF213 is basically the eyes of the immune system,” Coers says.

By blinding mysterin in this fashion, the killing signal never starts. The inside of a cell is swarming with “bags” called vacuoles, tiny bubbles covered by membranes. Most are friends, but some, like the Chlamydia inclusion, are foes.

“There’s so many different types of membranes and vacuoles that live inside a cell,” Coers explains. “How is the immune system able to find the rare vacuole that contains a pathogen? In the case of Chlamydia, we really don’t have the answer to that question. But whatever it is, we believe this enzyme (mysterin) is seeing it.”

Study authors repeated the experiments using a mouse-adapted version of the bacteria in human cells to see how the immune system responded to an alien pathogen.

“Humans, don’t get mouse Chlamydia because it evolved with mice and human Chlamydia evolved with humans,” the researcher continues. “So there’s this really fine-tuned adaptation that the pathogen has undergone.”

The rodent model of the bacterial inclusion was readily identified and labelled for destruction in human cells.

“Chlamydia trachomatis is so good at evading our human responses,” Coers notes. “It still causes an inflammatory disease, but it’s a very slow disease.”

Why use mice to examine STDs?

The evolutionary arms race between the immune system and the pathogen has been going on for millions of years.

“Mouse and human adapted Chlamydia have a common ancestor,” the researcher reports. “However, this common ancestor may go back as far as when humans and rodents basically split from each other. This is a long time for the bacteria to really fine-tune their interactions with their host species.”

The key to a therapy now lies in figuring out how GarD blinds mysterin, Prof. Coers notes.

“If you could find a mechanism to deactivate GarD, then you can turn human Chlamydia into mouse Chlamydia,” Coers concludes. “That would allow us to harness the powers of our own immune system to clear infection.”

Most people with Chlamydia do not know they have it. However, symptoms can include pain when urinating or unusual discharge or bleeding from the vagina, penis, or anus.

The study is published in the journal Cell Host & Microbe.

South West News Service writer Mark Waghorn contributed to this report.