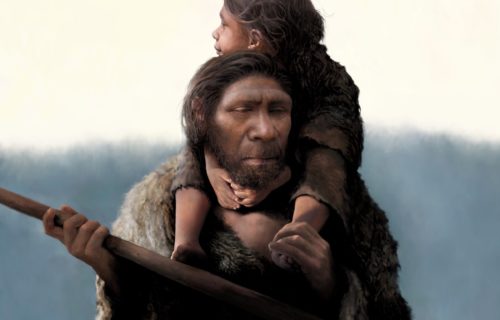

LEIPZIG, Germany — Researchers are introducing us to the first Neanderthal family. An analysis of ancient genomes from 13 individuals shows they lived in socially organized communities, just like modern humans.

They ate, slept, loved, and died in the company of their kin and were connected to others — forming a region’s Neanderthal population. An international team mapped DNA from the bones of eight adult males and five children to reveal more clues about our ancient cousins. Their findings provide the first snapshot of an actual family that lived 54,000 years ago.

“Our study provides a concrete picture of what a Neandertal community may have looked like,” says study author Benjamin Peter from the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in a university release. “It makes Neandertals seem much more human to me.”

Eleven of the specimens come from remains unearthed in Chagyrskaya Cave in the Alta Mountains of southern Siberia. They include a father and his teenage daughter, along with a pair of second-degree relatives — a young boy and an adult female, perhaps a cousin, aunt, or grandmother. The fascinating combination suggests they must have lived, and died, at around the same time.

The other two samples are from nearby Okladnikov Cave. It is the largest known genetic study of Neanderthals to date. These prehistoric people occupied western Eurasia from around 430,000 to 40,000 years ago and are closely related to modern humans.

“The fact that they were living at the same time is very exciting. This means that they likely came from the same social community. So, for the first time, we can use genetics to study the social organization of a Neandertal community,” says Laurits Skov, first author on the study.

Neanderthal families stayed in small groups

Another striking finding is the extremely low genetic diversity, consistent with a group size of 10 to 20 individuals. This is much lower than those for any ancient or present-day human community and is more similar to the sizes of endangered species at the verge of extinction.

The study in the journal Nature found genetic diversity of mitochondrial DNA, inherited from mothers, was much higher than that for the Y chromosome passed from father to son.

It suggests these communities were primarily linked by female migration. Moreover, it did not involve Denisovans that occupied Denisova Cave 60 miles away. There was no evidence of gene flow from this other group of mysterious ancient humans over the previous 20,000 years.

In their mitochondrial DNA, the researchers found several heteroplasmies that were shared between individuals. These are a special kind of genetic variant that only persists for a small number of generations.

Scientists have retrieved DNA from just 18 Neanderthals since the first draft genome was published in 2010. They have provided a broad review of the population, but little has been about their social organization, until now.

Chagyrskaya Cave is a Neanderthal treasure trove

Chagyrskaya Cave has been excavated over the last 14 years, producing one of the largest assemblages of its kind in the world. Besides several hundred thousand stone tools and animal bones, Russian scientists recovered more than 80 bone and tooth fragments of Neanderthals.

Scientists believe the Neanderthals at Chagyrskaya and Okladnikov hunted ibex, horses, bison, and other animals that migrated through the river valleys that the caves overlook. They collected raw materials for their stone tools tens of miles away. The occurrence of the same raw material also supports the genetic data that the groups inhabiting these localities were closely linked.

Previous studies of a fossilized toe from Denisova cave showed that Neandertals inhabited the Altai mountains considerably earlier as well, around 120,000 years ago. Genetic data shows the Neanderthals are not descendants of these earlier groups but are closer related to European Neanderthals.

This is also supported by the archaeological evidence. The stone tools from Chagyrskaya Cave are most similar to the so-called Micoquian culture of Germany and Eastern Europe.

“The findings can be best explained by a small community size – around 20 individuals – where 60% or more of females migrated from another community to join their mates’ families while the males stayed put,” Dr. Skov says, according to a statement from SWNS.

Rewriting the perception of Neanderthal society

The findings further erode the stereotypical image of Neanderthals as knuckle-dragging brutes. This is the most convincing evidence yet that females resided with their partners’ family.

“Our own species has a uniquely fluid social structure within which bonds of marriage are a central feature,” Dr. Lara Cassidy, a geneticist at Trinity College Dublin who did not take part in the study, tells SWNS.

“Detailed analysis of present-day hunting and gathering societies shows both men and women frequently move between groups and that dispersed relatives often maintain lifelong ties – which is not the case for apes. A father whose daughter moves to another community is able to recognize his grandchildren as kin and to bond with – or at least tolerate – his son-in-law.”

“This can allow vast social networks to form, if population densities are high enough,” Dr. Cassidy tells SWNS. “Whether this level of flexibility and cooperation is unique to Homo sapiens – and perhaps part of our success story – or a trait shared with our closest relatives remains to be seen. Chagyrskaya Cave and other sites across Eurasia have many more secrets to yield.”

Previous studies show that Neanderthals may have also been sophisticated, deep thinkers. They buried their dead and were capable of complex communication. They are believed to have gone extinct due to a combination of climate change and being outcompeted for resources by other cultures.

South West News Service writer Mark Waghorn contributed to this report.