JERUSALEM — The pain could finally be taken out of those tricky furniture shipments that arrive flat and require you to decipher poorly-written assembly instructions. That’s because scientists are developing innovative chairs and tables that assemble themselves after being removed from their packaging.

This next generation of flat-pack technology “shape shifts” into its final product, which one day could include beds and sofas. Wooden objects created by a 3D printer can be programmed to self-morph into complex forms. They are usually made by sawing, carving, bending or pressing. But that’s so old school, according to the Israeli team behind the new development.

Scientists say the new technique opens the door to reducing shipping costs to a destination. When the product is removed from the package and begins to dry, it forms into its design. The process is similar to the way plants and even some animals can alter appearance or textures. After a tree is cut down, its wood alters as it dries. It shrinks unevenly and warps because of variations in fiber.

“Warping [into a 3D shape] can be an obstacle. But we thought we could try to understand this phenomenon and harness it into a desirable morphing,” explains Doron Kam, a graduate student at The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, in a statement.

Furniture assembles itself — by drying

Artificial structures can’t shape themselves. So how are these seemingly flat products turning into 3D shapes? They just need a stimulus, such as a change in temperature or acidity or moisture content.

This furniture is also made from synthetic materials, such as gels and elastomers, notes principal investigator Dr. Eran Sharon. “We wanted to go back to the origin of this concept, to nature, and do it with wood,” he says.

A few years ago the researchers came up with an environmentally friendly water-based ink composed of wood-waste microparticles. The “wood flour” is mixed with cellulose nanocrystals and xyloglucan, which are natural binders extracted from plants. They then began using the ink in a 3D printer.

They recently discovered the way the ink is laid down dictates a piece’s morphing behavior as the moisture content evaporates. For instance, a flat disk printed as a series of concentric circles dries and shrinks to form a saddle-like structure reminiscent of a Pringles potato chip. A disk printed as a series of rays emanating from a central point turns into a dome or cone-like structure. Ultimate shape can also be controlled by adjusting print speed.

Shrinkage occurs perpendicular to the wood fibers in the ink, and print speed changes the degree of their alignment. A slower rate leaves the particles more randomly oriented, so shrinkage occurs in all directions. Faster printing aligns them with one another, so shrinkage is more directional.

Innovative tech could cost less, too

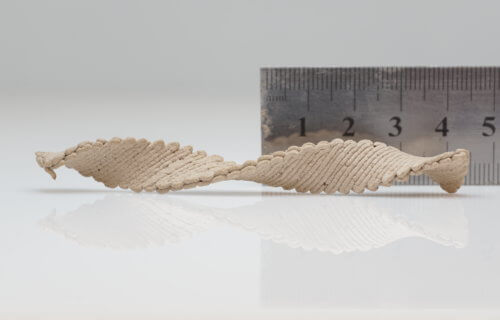

The scientists learned how to program the print speed and pathway to achieve a variety of final shapes. They say stacking two rectangular layers that are printed in different orientations yields a helix after drying. They also reveal that they can program the printing pathway, speed and stacking to control the specific direction of shape change, such as whether rectangles twist into a helix that spirals clockwise or counterclockwise.

Further refinement will allow the team to combine the saddles, domes, helices and other design motifs to produce objects with complicated final shapes, such as a chair. Ultimately, it could be possible to make wood products that are shipped flat to the end user, which could reduce shipping volume and costs.

“Then, at the destination, the object could warp into the structure you want,” adds Sharon.

Eventually, it might be feasible to license the technology for home use so consumers could design and print their own wooden objects with a regular 3D printer. The researchers are also exploring whether the morphing process could be made reversible.

“We hope to show that under some conditions we can make these elements responsive – to humidity, for example – when we want to change the shape of an object again,” adds Sharon.

The findings of the study, funded by the Israeli Ministry of Science, Technology and Space, were presented at an American Chemical Society meeting in Chicago.

Report by Mark Waghorn, South West News Service

Why not? Fauci created a shot that assembles itself into a nano-device within your body.