HOUSTON — Plenty of people fear visiting their local dentist will be a painful ordeal. However, researchers from Rice University say regular visits to the dentist now might help prevent a different type of pain later in life. Their study finds robust oral health (taking care of one’s teeth) can help patients avoid chronic joint pain.

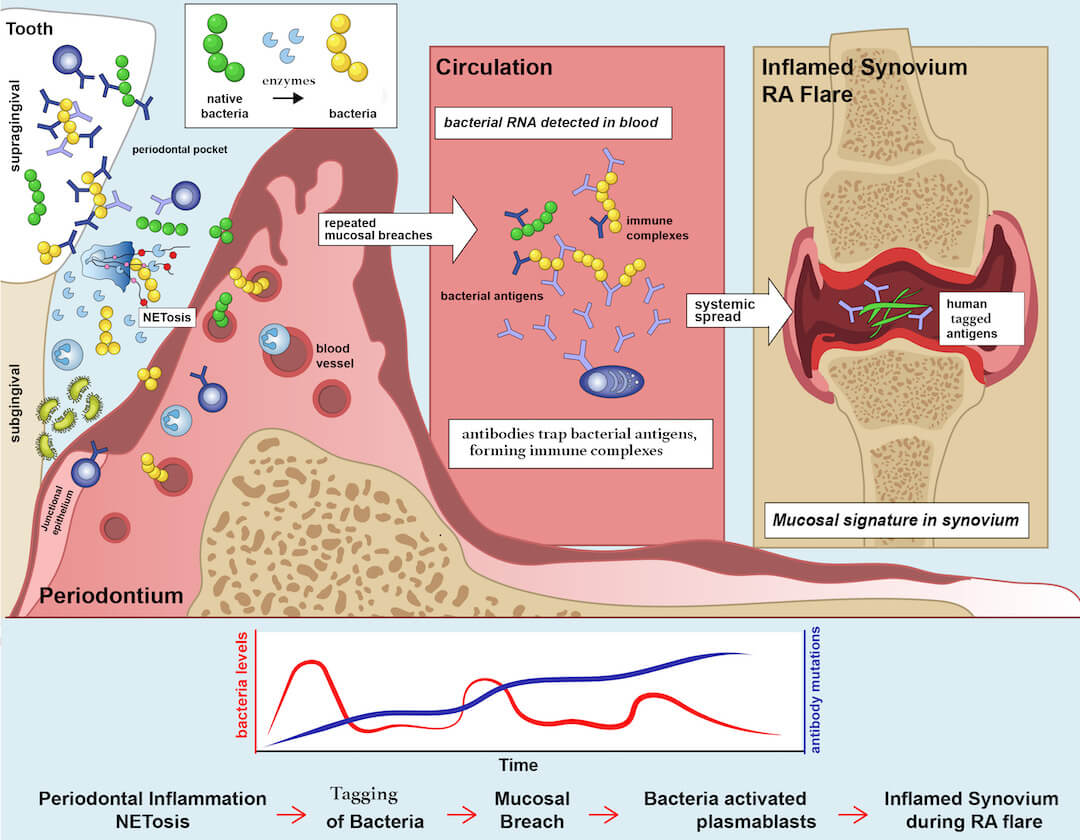

This project all started when Rice University computational biologist Vicky Yao discovered traces of bacteria associated with periodontal disease in samples from rheumatoid arthritis patients. Initially, she was not sure what to make of it.

Fast forward to today, and her work is helping jumpstart an entire series of experiments — seemingly confirming a connection between arthritis flare-ups and gum disease. Continuing to research and trace this connection between the two connections may one day lead to the development of new therapies for rheumatoid arthritis. Moreover, the approach study authors used during this project could prove fruitful in fighting other diseases as well, such as cancer.

“Data gathered in experiments from living organisms or cells or tissue grown in petri dishes is really important to confirm hypotheses, but, at the same time, this data perhaps holds more information than we are immediately able to derive from it,” Prof. Yao says in a university release.

So, what do your teeth have to do with joint problems?

Prof. Yao’s confirmed her hunch after taking an even closer look at the data collected from rheumatoid arthritis patients by Dana Orange, an associate professor of clinical investigation and a rheumatologist, and Bob Darnell, a professor and attending physician at Rockefeller University and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. Yao was collaborating with Orange and others on a different project tracking changes in gene expression during rheumatoid arthritis flare-up periods.

“Orange, working with Darnell, collected data from arthritis patients at regular intervals while, at the same time, monitoring when the flares happened,” Prof. Yao explains. “The idea was that perhaps looking at this data retroactively, some pattern would become visible giving clues as to what might cause the arthritis to flare up.”

“While I was working on that project, I went to this talk that I thought was really cool because it pointed out that in the data that gets ignored or thrown out, you can actually find traces of microbes. You’re looking at a human sample but you get a snapshot of the microbes floating around. I was intrigued by this.”

Upon closer examination, Yao discovered the germs in the samples that changed consistently across patients prior to flares were largely the same ones associated with gum disease.

“I was curious about this tool that allowed you to detect microbes in human samples. It was sort of like, for free, you’re getting an extra perspective on the data,” Prof. Yao continues. “At the time, I hadn’t worked much on microbial data at all. Since then, Dana leveraged all this expertise and got together with people studying these bacteria.

“One of the things that came up when we were discussing this was, how cool would it be if you could prescribe some kind of mouthwash to help prevent rheumatoid arthritis flares.”

The discovery could lead to new treatments for cancer

Since 2019, Yao’s has shifted her primary focus to cancer research. Still, discovering meaningful information in largely discarded data inspired her to take a similar approach while looking at health records from cancer patients.

“I got really interested in what else we can find mining for microbial signatures in human samples,” Prof. Yao adds. “Now, we’re doing something similar in looking at cancer.”

“The hope here is that if we find some interesting microbial or viral signatures that are associated with cancer, we can then identify productive experimental directions to pursue. For instance, if having a tumor creates this hotbed of specific microbes that we recognize, then we can maybe use that knowledge as a means to diagnose the cancer sooner or in a less invasive or costly way. Or, if you have microbes that have a very strong association with survival rates, that can help with prognosis. And if experiments confirm a causal link between a specific virus or bacteria and a type of cancer, then, of course, that could be useful for therapeutics.”

One of the most well-known examples of a pathogen linked to cancer is the human papillomavirus (HPV). Prof. Yao decided to use this well-documented connection to verify her approach.

“When we did the same exercise looking at cervical cancer tumor samples, we consistently detected the virus,” the study author concludes. “It’s a nice proof-of-principle finding that shows that the presence of specific pathogens can be meaningful for certain types of cancer.”

“I’m really interested in using computational approaches to bridge the gap between available experimental data and ways to interpret it. Computational analysis is a way to help interpret data and prioritize hypotheses for clinicians or experimental scientists to test.”

The study is published in the journal Science Translational Medicine.