OXFORD, United Kingdom — Having good friends could be essential for a healthy stomach, according to new research. Researchers from the University of Oxford found that friendship is just as important for our physical health as it is for our mental well-being.

The research team discovered that the more social monkeys are, the more beneficial gut microbes they have in their system. Prior to the study, evidence showed that a person’s gut microbiome plays a major role in physical and mental health, linked by the “gut-brain axis.”

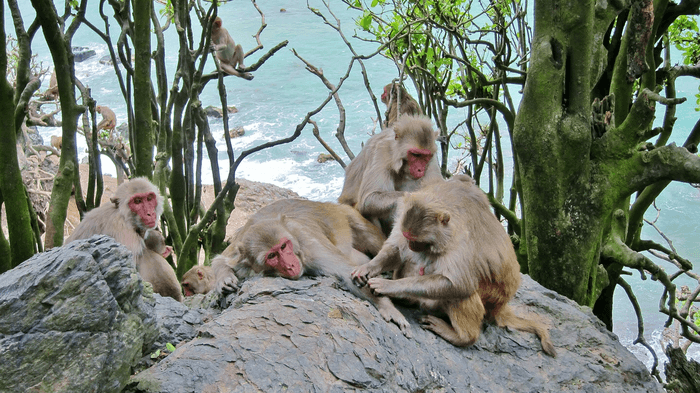

Bacteria can be transmitted socially, by something as simple as a touch, and scientists investigated how this process affects rhesus macaques. They discovered the good gut bacteria abundant in the more sociable monkeys had strong immunological functions and brilliant anti-inflammatory properties. At the same time, the sociable monkeys had less toxic microbiota.

Monkeys who spent less time hanging out with their friends had higher quantities of Streptococcus, the bacteria that causes diseases such as strep throat and pneumonia in humans. The team says their findings, published in Frontiers in Microbiology, demonstrates how our perennially online and highly social world evolved from a microbial one.

“Here we show that more sociable monkeys have a higher abundance of beneficial gut bacteria, and a lower abundance of potentially disease-causing bacteria,” says lead author Dr. Katerina Johnson, a research associate at the Department of Experimental Psychology and the Department of Psychiatry of the University of Oxford, in a media release.

Monkey poop reveals how sociable the animals are

The team studied one social group of rhesus macaques living on the island of Cayo Santiago, off the eastern coast of Puerto Rico. It contained 22 males and 16 females between the ages of six and 20. Over 1,000 macaques live on the 15.2-hectare island — living in several social groups.

Between 2012 and 2013, the authors studied 50 stool samples from the social group. To measure the monkeys’ level of social connection, they looked at the time each animal spent grooming, being groomed, and how many grooming partners they had.

“Macaques are highly social animals and grooming is their main way of making and maintaining relationships, so grooming provides a good indicator of social interactions,” explains co-author Dr. Karli Watson from the Institute of Cognitive Science at the University of Colorado-Boulder.

The team then measured the composition and diversity of the gut microbes in the stool samples, focusing on the microbes which were more or less abundant in people or rodents with autism-like symptoms and those who were socially deprived. Next, the team looked at how the monkeys socialized.

“Engagement in social interactions was positively related to the abundance of certain gut microbes with beneficial immunological functions, and negatively related to the abundance of potentially pathogenic members of the microbiota,” says co-author Dr. Philip Burnet, a professor from the Department of Psychiatry at the University of Oxford.

Which microbes are floating around in social creatures?

Faecalibacterium and Prevotella are more common in the most social monkeys and Streptococcus was more abundant in less sociable monkeys.

“It is particularly striking that we find a strong positive relationship between the abundance of the gut microbe Faecalibacterium and how sociable the animals are. Faecalibacterium is well known for its potent anti-inflammatory properties and is associated with good health,” Johnson says.

“The relationship between social behavior and microbial abundances may be the direct result of social transmission of microbes, for example through grooming. It could also be an indirect effect, as monkeys with fewer friends may be more stressed, which then affects the abundance of these microbes. As well as behavior influencing the microbiome, we also know it is a reciprocal relationship, whereby the microbiome can in turn affect the brain and behavior.”

“As our society is increasingly substituting online interactions for real-life ones, these important research findings underline the fact that as primates, we evolved not only in a social world but a microbial one as well,” adds co-author Dr. Robin Dunbar, a professor from the Department of Experimental Psychology at the University of Oxford.

South West News Service writer Pol Allingham contributed to this report.