GREENBELT, Md. — Black holes are notorious for gobbling up nearby objects in space, and the Hubble Telescope has just spotted another cosmic meal in progress! Researchers from NASA are revealing their findings after a supermassive black hole shredded a nearby star — turning it into a “donut” the size of our solar system!

Here’s what you need to know about black holes:

- Black holes often form when large stars collapse and cause a supernova.

- A black hole’s gravitational pull is so strong even light can’t escape.

- Black holes are technically invisible, so scientists really on the behavior of nearby stars to know they’re there.

- The biggest black holes are called “supermassive,” and scientists believe they sit at the heart of many galaxies.

The new findings from March 2022 spotted a black hole approximately 300 million light years away pulling in a local star in the galaxy ESO 583-G004. Astronomers used Hubble’s powerful ultraviolet sensitivity to study the light and chemicals coming from the doomed star. These include hydrogen and carbon just to name a few.

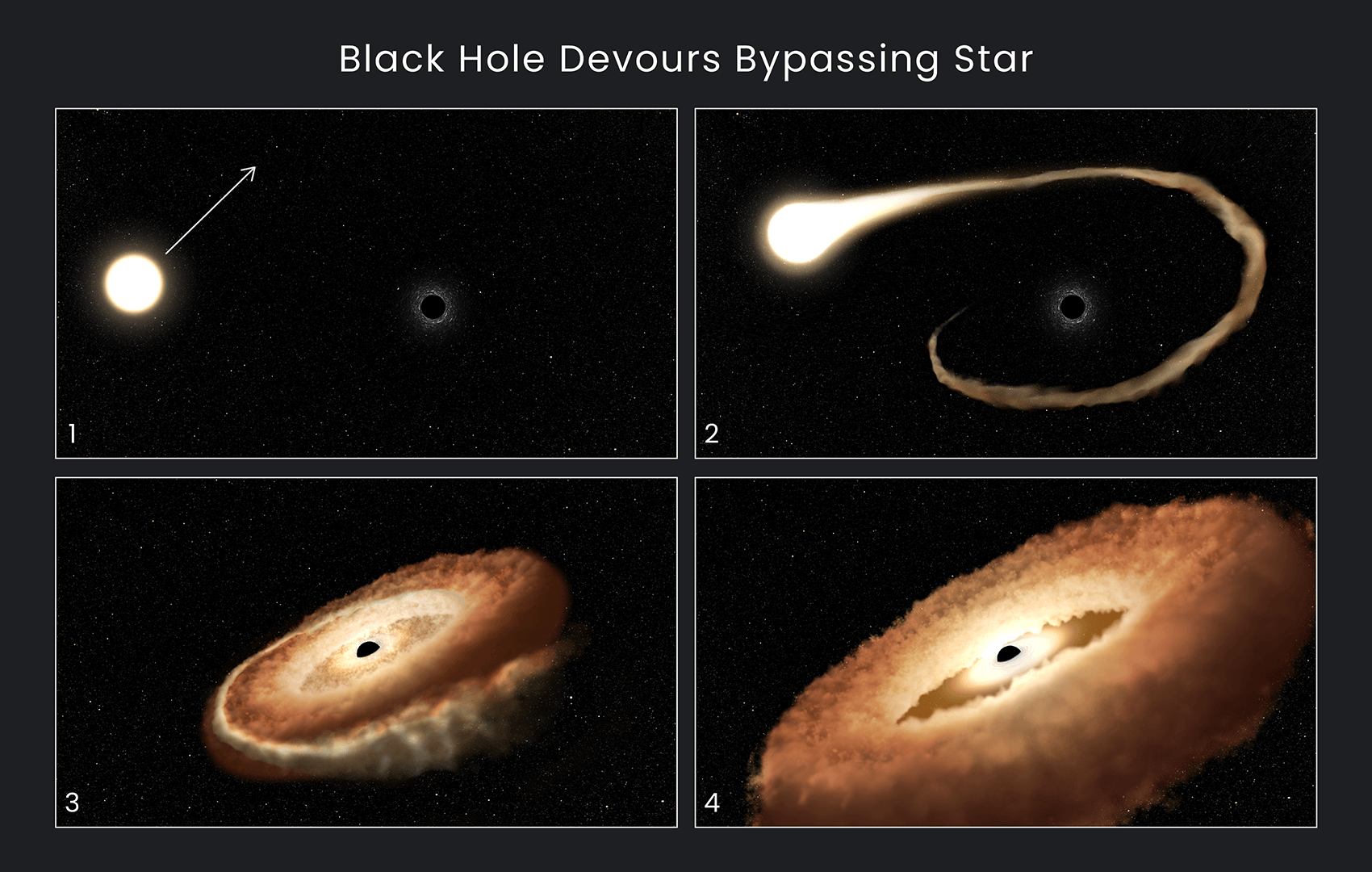

Scientists call these stellar homicides a “tidal disruption event.” While that doesn’t sound so violent, the NASA team explains that black holes are “messy eaters,” balancing out the star matter they pull in by blowing out just as much.

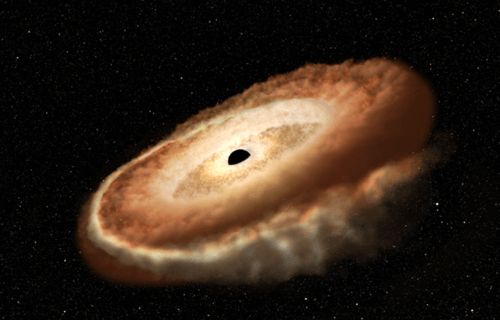

Credits: NASA, ESA, Leah Hustak (STScI)

How often do black holes turn stars into donuts?

Study authors say a galaxy with a supermassive black hole at the center shreds a star in this way only a few times every 100,000 years.

This particular event, called AT2022dsb, was first observed on March 1st, 2022 by the All-Sky Automated Survey for Supernovae (ASAS-SN or “Assassin”). It’s a network of ground telescopes which watch the sky for violent, variable, and transient events across the universe.

Despite being 300 million light years away, scientist say it’s still close enough to Earth and bright enough for the Hubble Telescope to use its ultraviolet spectroscopy on this donut-making event.

“Typically, these events are hard to observe. You get maybe a few observations at the beginning of the disruption when it’s really bright. Our program is different in that it is designed to look at a few tidal events over a year to see what happens,” says Peter Maksym of the Center for Astrophysics | Harvard & Smithsonian (CfA) in a media release. “We saw this early enough that we could observe it at these very intense black hole accretion stages. We saw the accretion rate drop as it turned to a trickle over time.”

Although the event is too far away to see with the naked eye, scientists interpret Hubble’s data as coming from the very bright, hot, donut-shaped area of gas now swirling around the black hole. The team calls this area the torus and say this particular donut is as big as our entire solar system.

“We’re looking somewhere on the edge of that donut. We’re seeing a stellar wind from the black hole sweeping over the surface that’s being projected towards us at speeds of 20 million miles per hour (three percent the speed of light),” says Maksym. “We really are still getting our heads around the event. You shred the star and then it’s got this material that’s making its way into the black hole. And so you’ve got models where you think you know what is going on, and then you’ve got what you actually see. This is an exciting place for scientists to be: right at the interface of the known and the unknown.”

The NASA team reported their findings at the 241st meeting of the American Astronomical Society in Seattle.