NEW YORK — Humans carry a protein that wipes out germs “like a laundry detergent,” according to a new study. Researchers say the “killer cleaner” thwarts infections by dissolving the outer layer – or membrane – of bacteria.

The team adds harnessing this power could hold the key to combating harmful, antibiotic-resistant superbugs — which can lead to life-threatening infections.

Lead author Professor John MacMicking, a microbiologist at Yale University, notes cells fend off germs with cleaning products just like people do in their own homes. The chemical’s discovery sheds new light on how the human body defends themselves.

Tests on the food-poisoning bug Salmonella and other microbes discovered that it acts similar to soap attacking an oily stain.

Health officials consider superbugs to be a global public health threat. Antibiotic resistance claims more than 700,000 lives each year, a figure experts expect to rise to 10 million by 2050.

“This is a case where humans make their own antibiotic in the form a protein that acts like a detergent. We can learn from that,” MacMicking says in a media release.

Discovering the molecules that break down bacteria

Study authors say the miracle molecule, APOL3, is made throughout much of the body. The findings reveal this phenomenon, called cell-autonomous immunity, is the first line of defense against disease causing organisms. Researchers add a specialized “crew of bodyguards” can also activate this immunity. A chemical called interferon gamma cranks up proteins in tissues and organs.

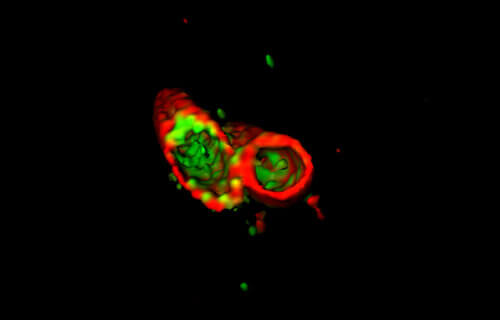

Researchers infected non-immune cells with a strain of Salmonella, which invades the watery interiors. The outer bacterial membrane acts like armor, protecting the inner lining from antibiotics. The interferon gamma alarm signal however, prevents Salmonella from taking over human cells.

Prof. MacMicking and colleagues found that APOL3 receives assistance from a second molecule, GBP1, although other may help too. Powerful scanners revealed GBP1 damages a bacterium’s outer membrane, allowing APOL3 through. The “detergent” then breaks apart the inner membrane and kills the bacterium.

Prof. MacMicking says, just like a laundry detergent, APOL3 possesses parts which are attracted to water and parts that seek out to grease. Instead of removing dirt from fabric, these components remove chunks of the bacterial inner membrane — greasy molecules called lipids.

The process must be highly selective since APOL3 needs to avoid attacking membranes of the human cell itself. The experiments also showed APOL3 avoids cholesterol, a major part of cell membranes and, instead, targets distinctive fats favored by bacteria.

‘Detergent’ proteins are everywhere in the body

The protein is in the toolbox of many cells. The study, in the journal Science, finds it defends cells within both the blood vessels and gut. APOL3 also appears in a variety of body tissues, offering wide protection.

Prof. Carl Nathan, a microbiologist at Weill Cornell Medical College, says the discovery of this detergent-like molecule “adds more evidence to the view that any cell in the body can be part of the immune system.”

The professor, who did not take part in this study, notes that the immune system has developed several methods for killing threatening cells. He adds that APOL3 joins the group of mechanisms that fatally breaks down membranes.

Prof. MacMicking says deciphering the body’s defenses could give humanity new tools against microbes that are increasingly evolving ways to thwart conventional antibiotics. Dialing up “cellular detergents” and other devices the body uses to kill bacteria could help supplement the natural immune response.

SWNS writer Mark Waghorn contributed to this report.