PRINCETON, N.J. — Brace yourself for some gnarly hurricane seasons in the coming years, research suggests. Scientists are predicting back-to-back hurricanes in coastal areas in the next few decades. Some areas, like the Gulf coast of the United States, will likely see double hits once every three years, according to new estimates.

“Rising sea levels and climate change make sequential damaging hurricanes more likely as the century progresses,” says study lead author Dazhi Xi, a postdoctoral researcher and a former graduate student in civil and environmental engineering at Princeton University, in a university release. “Today’s extremely rare events will become far more frequent.”

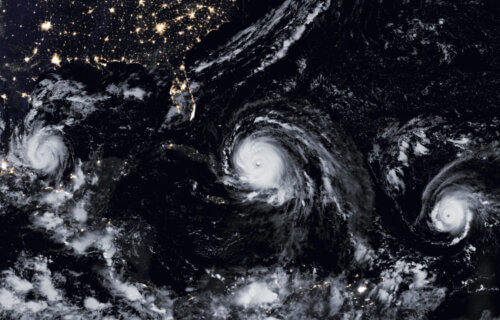

The study authors first asked the question about successive storms after witnessing a destructive hurricane season in 2017. In one summer, three major hurricanes hit the U.S. Hurricane Harvey hit Texas, followed by Irma in South Florida, and Maria in Puerto Rico. Additionally, 2021 showed continuous hurricane activity when Ida struck Louisiana, followed shortly by Tropical Storm Nicholas, which first made landfall as a hurricane in Texas.

“Sequential hurricane hazards are happening already, so we felt they should be studied,” says Ning Lin, an associate professor of civil and environmental engineering at Princeton University and study co-author. “There has been an increasing trend in recent decades.”

What’s driving the rise in double hurricanes?

In the current study, the authors used computer simulations to estimate the chances of multiple storms hitting an area within a 15-day period. They considered two scenarios. The first was a future with moderate carbon emissions and the next was one with higher emissions. Both cases showed a substantial increase in sequential and damaging hurricanes.

Climate scientists have predicted for some time that climate change will increase the intensity of Atlantic hurricanes as this century progresses. However, it’s unknown whether climate change will increase, decrease, or maintain the number of storms we’ll get each season.

Even if there was no increase in the frequency of storms, Lin’s team warns the increased intensity of Atlantic hurricanes will make it more likely Americans will experience sequential tropical storms that can become almost as dangerous as a hurricane.

“The proportion of storms that can have an impact on communities is increasing,” Lin says. “The frequency of storms is not as important as the increasing number of storms that can become hazardous.”

The danger comes from two factors: rising sea levels and the increased rainfall driven by climate change. A higher sea level causes storms to surge and become more of a threat to coastal communities since the baseline water level is higher.

A three-meter storm surge on top of a zero-meter water level is less damaging to roads than the same surge on top of a half-meter water level. As storms are intensifying and higher average air temperatures cause storms to carry more water, the end result is increased rainfall and flooding.

The study authors suggest storms that would have been mild in the past will soon become threats, especially as they leave no time for people to prep and recover for the next event. We can see this in the 2021 tropical storm in Louisiana. Tropical Storm Nicholas was weak when it hit the Pelican state but it caused a lot of problems since it arrived at a time when residents were still recovering from Hurricane Ida.

“Nicholas was quite a weak storm and one reason it produced a significant hazard was that the soil was already saturated,” Lin says. “So, there was a lot of flooding.”

How can the nation prepare for multiple storms?

There is still time for community planners and regional emergency officials to prepare for this inevitable threat. For example, communities can strengthen systems involved in removing floodwater and protecting infrastructures such as water systems, transportation, and power grids. Emergency response teams will have to prepare for multiple storms in quick succession. State and federal government officials will have to have resources on hand and ready to dispatch once a community is hit.

“If a power system requires 15 days to recover from a major hurricane, we cannot wait that long in the future because the next storm can hit before you can restore power, as in the case of Nicholas following Ida,” says Lin. “We need to think about plans, rescue workers, resources. How will we plan for this?”

The study is published in the journal Nature Climate Change.

Just think of NOAA’s spaghetti storm path predictions published just days and hours out from storms making landfall. With most being wrong. So an engineer wants us to believe climate impacts on storms in the future years, decades from now can be predicted now. Amazing storms come in cycles. Increasing in strength and number and then receding in both strength and number again as the cycles pass. Mostly tied to the SUN.