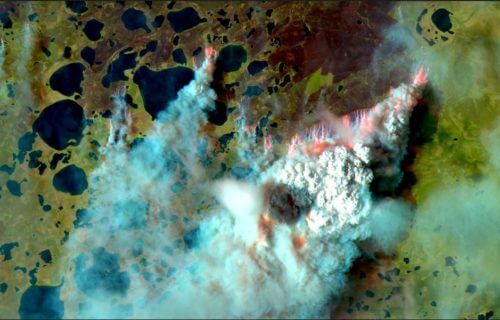

MADRID, Spain — Global warming is driving an exponential increase in megafires across the Arctic, new research warns.

In 2020, fires destroyed an area almost as large as Belgium, with recent fire rates in the Siberian Arctic exceeding those of the last four decades. The number of fires was seven times higher than the average since 1982, according to the study.

Scientists in Spain attribute this dramatic increase to rising temperatures as the summer of 2020 was the warmest in the last 40 years. Approximately 4.7 million hectares burned between 2019 and 2020, resulting in total emissions of 412.7 million tons of greenhouse gases.

Hundreds of fires are burning through the Arctic

The increase of fires has had multiple consequences. The Arctic has large areas of permafrost, which is a permanently frozen layer of subsoil that accumulates large amounts of carbon. With the rise of fires, the permafrost has been damaged, causing a huge release of greenhouse gases. Fires also destroy the dynamic habitats and ecosystems that have been thriving for years.

“In 2020 alone, 423 fires were detected in the Siberian Arctic, which burned around 3 million hectares (an area almost as big as the whole Belgium) and caused the emission of 256 million tons of CO2 equivalent,” explains first author Adrià Descals from the Spanish Council for Scientific Research (CSIC) in a media release.

“Temperatures are reaching a critical threshold where small increases above the summer average of 10 °C can exponentially increase the area burned and the associated emissions,” explains study co-author and CSIC scientist Josep Peñuelas.

“The 2020 average summer temperature – which was 11.35 degrees – will be very common from the second half of the century on if the Arctic warming continues at the same rate,” the researchers add. “These temperature anomalies increase fire risk factors, so the conditions that were led to the 2019 and 2020 fires will be recurrent in the Arctic by the end of the century.”

More vegetation is actually bad in the Arctic

Problems resulting from higher temperatures such as drier weather conditions, longer summers, and more vegetation have shown a consistent trend over the past four decades and contribute to the rise in fires.

“Higher temperatures explain the earlier thaw, which in turn allows for greater vegetation growth and increases fuel availability,” Dr. Peñuelas says.

“The fact that there is more and earlier vegetation reduces the availability of water in the soil, and plants suffer greater water stress,” explains Aleixandre Verger, a researcher at CSIC and CREAF. “Extreme heat waves, such as in 2020 in the Siberian Arctic, increase vulnerability to drought, as they can desiccate plants and reduce peat moisture, and therefore increase the intensity of fires and carbon emissions.”

Rising temps are even causing more extreme weather

One other key consequence of these rising temperatures is an increase in storms and lightning, which have been very rare in the Arctic until now.

“We detected fires above the 72nd parallel north, more than 600 km north of the Arctic Circle, where fires are unusual and where winter ice was still visible at the time of burning,” Descals says. “Many fires were detected with a few days of difference, so we hypothesize that increases in thunderstorms and lightning are the main cause of the fires, although further investigations would be required to demonstrate how much human activities may influence the fire season in this remote region.”

“Climate warming therefore has a double effect on fire risk: it increases the susceptibility of vegetation and peatlands to fire and, on the other hand, it increases the number of ignitions caused by thunderstorms.”

“The areas burned in 2019 and 2020 could be exceptional events, but recent temperature trends and projected scenarios indicate that, by the end of the century, large fires such as those in 2019 and 2020 will be frequent if temperatures continue to increase at the current rate,” Descals and Peñuelas conclude.

The study is published in the journal Science.

South West News Service writer Alice Clifford contributed to this report.