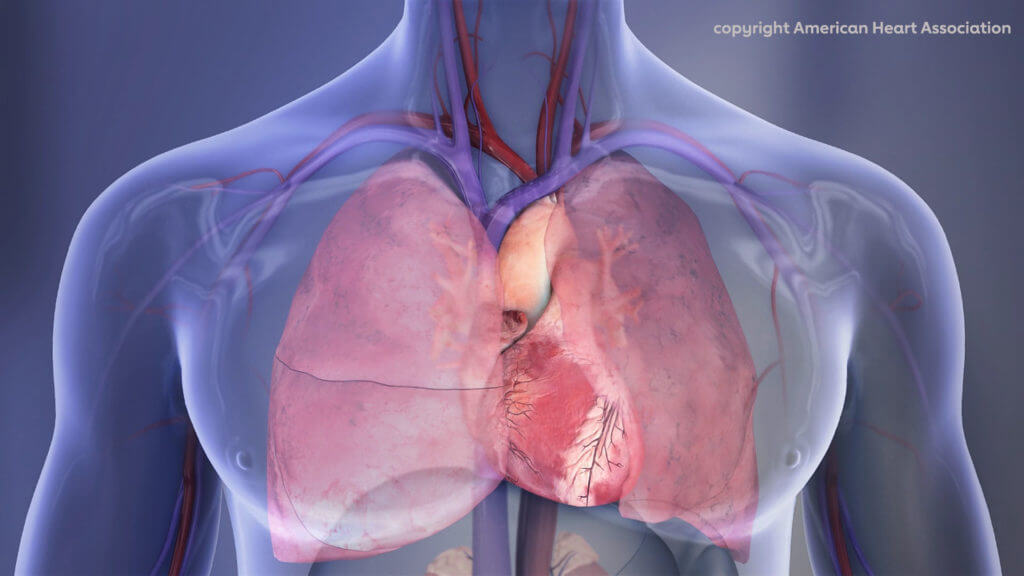

DALLAS — The first ever pig-to-human heart transplant lasted only 61 days. Now, doctors say they’ve found “unexpected differences” in the electrical conduction system of the genetically-modified heart that surgeons used in the procedure.

In a new study, researchers with the University of Maryland School of Medicine discovered that the electrocardiogram (ECG) measures after the transplant were noticeably different from those documented after pig-to-pig heart transplants. Typically, ECG measures are shorter in a pig than in a human. However, the ECG measures after the January 2022 surgery were surprisingly longer.

The 57-year-old who underwent xenotransplantation — an organ transplant from one species to another — was suffering from terminal heart disease at the time. The surgery was the first to ever use a genetically-modified pig heart in a human transplant. That man survived for another 61 days before dying. However, a previous study reported that the cause of death was not organ rejection.

“There are several potential challenges for transplanting a pig heart into a human. With any transplant including this one, there is always the risk of rejection, the potential risk of infection and a third one is abnormal heart rhythms, and that is where the electrocardiogram (ECG) comes in,” says Timm Dickfeld, M.D., Ph.D., a professor of medicine and director of electrophysiology research at the University of Maryland School of Medicine in Baltimore, in a media release.

“It’s truly a novel finding that the ECG parameters of the pig heart after transplantation into a human were so different compared to the commonly found ECG parameters for native pig hearts.”

What was different about the pig-to-human transplant?

Study authors explain that monitoring the heart using ECG after a transplant is a common way of measuring the electrical conduction system. Specifically, the team looked at two different ECG measures in the pig heart transplant patient, the PR interval/QRS complex and the QT interval.

“The PR interval and QRS complex measure the time it takes electricity to travel from the top to the bottom chamber and across the bottom chambers, thus, pumping blood through the heart,” researchers explain.

Meanwhile, the QT interval measures the time it takes the heart’s lower chambers to complete a full electrical cycle associated with a heartbeat. Doctors kept track of this data every day after the xenotransplantation.

While previous studies have recorded a short PR interval (50 to 120 milliseconds), short QRS (70 to 90 milliseconds), and short QT (260 to 380 milliseconds) in pig-to-pig transplants, the research team found surprisingly different results after the January procedure.

“In contrast, the first-ever ECG of a genetically modified heart xenotransplant found a longer PR interval of 190 milliseconds, QRS duration of 138 milliseconds and QT of 538 milliseconds, which is longer than what would be expected from a pig heart in a pig body,” Dickfeld says.

“In a human heart, when those parameters get longer, this can indicate signs of electrical or myocardial disease,” the researcher continues. “The pig heart ECG parameters were extended to what we see in a human heart and often the measures even extended beyond what we consider normal in a human heart.”

The team adds that the prolonged PR intervals remained stable after the transplant, averaging about 210 milliseconds. The QRS duration also remained steady at about 145 milliseconds, but this shortened up throughout the 61 days the patient survived.

“The QRS duration may prolong when, for example, the muscle and the electrical system itself is diseased, and that is why it takes a long time for electricity to travel from cell to cell and travel from one side of the heart to the other,” Dickfeld says. “In general, we would prefer for this QRS measure not to prolong too much.”

Prolonged heart measurements can lead to dangerous heart rhythms

Study authors note that their study found an increased QT duration averaging 509 milliseconds with dynamic fluctuations.

“In the human heart, the QT duration is correlated with an increased risk of abnormal heart rhythms,” Dickfeld says. “In our patient, it was concerning that the QT measure was prolonged. While we saw some fluctuations, the QT measure remained prolonged during the whole 61 days.”

The team believes their findings will help other surgeons looking at xenotransplantation for heart patients. It can help them better prepare for the problems and differences that take place in the patient’s electrical system connected to the heart.

“The ultimate goal is that if someone needs a heart, xenotransplantation may be an option,” Dickfeld explains. “We need to make xenotransplantation safer and more doable in these challenging areas: rejection, infection, pumping problems and certainly in the area of abnormal electrical signals and heart rhythms.”

“This was a true milestone for research on xenotransplantation, the transplantation of organs from one species to another, in this case from pigs to human. There were a number of key steps that will be fundamental to the success of these operations largely centered around genetic manipulation to reduce organ rejection. Solving the problem of rejection may ultimately lead to use of this method to help numerous patients with advanced heart failure,” adds Paul J. Wang, M.D., FAHA, director of the Stanford Cardiac Arrhythmia Service and a professor of medicine and bioengineering at Stanford University, who did not take part in the study.

“It will be extremely interesting to understand the factors that affect the changes in the parameters observed comparing the pig-in-pig values vs. the pig-in-human values. We will want to look at factors such as how they reflect rejection and hemodynamic status,” Wang concludes. “Further analysis of the electrocardiogram including ST-T wave abnormalities may also provide unique insights.”

The team is presenting their findings at the American Heart Association’s Scientific Sessions 2022.