TOKYO, Japan — Moving to the rhythm of the music is a uniquely human skill, right? Not so fast. A new study finds people may not be the only ones capable of busting a move when a catchy tune comes on the radio!

Researchers at the University of Tokyo have discovered that rats can move their heads to a musical beat as well, debunking the theory that humans are the only species who can dance the night away. Their study found that the “optimal tempo” for nodding along to music depends on the time constant in the brain — the speed at which our brains respond to stimuli. This tempo is actually similar among all species on Earth.

The new findings reveal that the ability of the auditory and motor systems to interact and move along to music are more common among different kinds of animals than scientists thought. The Japanese team adds that their study provides even more insight into the animal mind.

Your dance moves may depend on your genes!

Study authors say how well people time out their movement to music partially depends on their innate genetic ability. It’s a skill scientists previously believed was unique to humans. Although animals also react to hearing noise and may even make rhythmic sounds, it’s not the same as recognizing the beat of a song and predicting the next movement to make. This skill is called beat synchronicity.

However, the new study examined recent observations and home videos of animals seemingly moving to the groove. Experiments in the University of Tokyo lab found that rats are one of these talented species.

“Rats displayed innate — that is, without any training or prior exposure to music — beat synchronization most distinctly within 120-140 bpm (beats per minute), to which humans also exhibit the clearest beat synchronization,” explains Associate Professor Hirokazu Takahashi from the Graduate School of Information Science and Technology in a media release. “The auditory cortex, the region of our brain that processes sound, was also tuned to 120-140 bpm, which we were able to explain using our mathematical model of brain adaptation.”

“Music exerts a strong appeal to the brain and has profound effects on emotion and cognition. To utilize music effectively, we need to reveal the neural mechanism underlying this empirical fact,” Takahashi adds. “I am also a specialist of electrophysiology, which is concerned with electrical activity in the brain, and have been studying the auditory cortex of rats for many years.”

It’s all about the clock in your brain

The team entered their experiments with two theories. The first was that the time constant of the body determines the optimal music tempo for beat synchronicity. This constant is different depending on the species and is much faster in smaller animals.

The second theory was that the time constant of the brain determines the optimal tempo. This constant is actually much more similar across all species.

“After conducting our research with 20 human participants and 10 rats, our results suggest that the optimal tempo for beat synchronization depends on the time constant in the brain,” Takahashi reports. “This demonstrates that the animal brain can be useful in elucidating the perceptual mechanisms of music.”

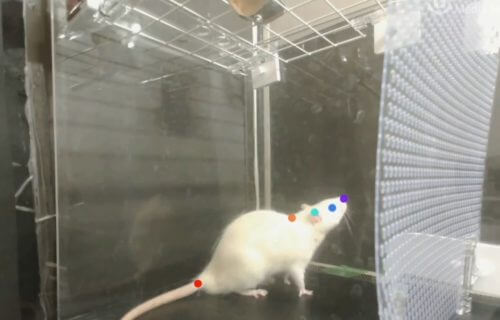

BELOW: Rat ‘Grooves’ To Mozart, Lady Gaga, Queen songs

Rats and humans have the same dance moves?

During the study, researchers fitted rats with wireless, miniature accelerometers, which measure the slightest head movements. Meanwhile, human participants wore accelerometers attached to headphones. Study authors then played one-minute excerpts from Mozart’s Sonata for Two Pianos in D Major, K. 448, at four different tempos to both the humans and animals.

The tempos included 75, 100, 200, and 400 percent of the music’s original speed. Normally, the tempo of Mozart’s sonata is 132 bpm.

Results reveal that the rats’ beat synchronicity was clearest within the 120 to 140-bpm range. The team also observed that rats and humans move their heads to the beat in a similar rhythm. Moreover, the level of head bopping decreased the more the tempo increased.

“To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report on innate beat synchronization in animals that was not achieved through training or musical exposure,” Takahashi says.

“We also hypothesized that short-term adaptation in the brain was involved in beat tuning in the auditory cortex. We were able to explain this by fitting our neural activity data to a mathematical model of the adaptation. Furthermore, our adaptation model showed that in response to random click sequences, the highest beat prediction performance occurred when the mean interstimulus interval (the time between the end of one stimulus and the start of another) was around 200 milliseconds (one-thousandth of a second). This matched the statistics of internote intervals in classical music, suggesting that the adaptation property in the brain underlies the perception and creation of music.”

“Next, I would like to reveal how other musical properties such as melody and harmony relate to the dynamics of the brain. I am also interested in how, why and what mechanisms of the brain create human cultural fields such as fine art, music, science, technology and religion,” the researcher concludes. “I believe that this question is the key to understand how the brain works and develop the next-generation AI (artificial intelligence). Also, as an engineer, I am interested in the use of music for a happy life.”

The findings are published in the journal Science Advances.

Not buyin’ it. Looks like a rat doing what rats do. Nothing special about his movements.

Same here. I’ve been a rat minder for years and this isn’t strongly convincing to me.

There are some key details that this report left out: the methods and the actual benefits derived from its findings (spoiler: there were none).

In order for the rats to be “fitted” with the accelerometers, experimenters cut away the tissue on the rats’ heads and drilled five screws into each animal’s skull. Then they glued an accelerometer to the rats’ skulls with dental cement.

As for the benefits of this “discovery,” the authors state that their findings “…offer insights into the origins of music and dancing.” In other words, idle academic curiosity.

Institutional ethics committees are supposed to prevent pointless animal experimentation such as this from occurring. As is seen elsewhere, they far too often fail to do so.