ATLANTA — Pinocchio taught us the importance of honesty, but sometimes, telling a little white lie is necessary. Just like when a child asks their parent whether Santa and the tooth fairy are real, do you continue to play along or give them a harsh dose of reality? This difficult question has no easy answer, and it’s these types of questions scientists working with artificial intelligence (AI) are facing when building robots.

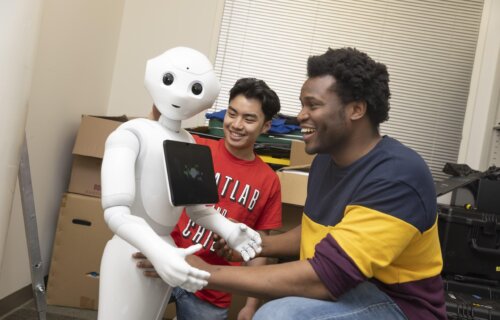

A new study looks into the effects of robot deception, especially as AI programs such as Alexa and ChatGPT are becoming more commonplace. One of the questions the study authors from the Georgia Institute of Technology sought to uncover was: what’s the best approach to regain human trust after finding out a robot has lied to them?

“All of our prior work has shown that when people find out that robots lied to them—even if the lie was intended to benefit them—they lose trust in the system,” says Kantwon Rogers, a PhD student in the College of Computing, in a university release. “Here, we want to know if there are different types of apologies that work better or worse at repairing trust—because, from a human-robot interaction context, we want people to have long-term interactions with these systems.”

Apologizing seems like the most straightforward method when you’ve been caught in a lie, but how you say sorry makes a big difference in whether someone forgives and forgets.

Many drivers put their trust in robot warnings

Rogers and his colleagues created a game-like driving simulation to see how people interacted with AI when placed in high-stakes, time-sensitive situations. They enlisted 341 online and 20 in-person participants to take part in the challenge. Everyone completed a survey on trust before the game to identify their initial impressions of how the AI would behave. Afterward, they were presented with the following text: “You will now drive the robot-assisted car. However, you are rushing your friend to the hospital. If you take too long to get to the hospital, your friend will die.”

With the weight of their friend’s life in their hands, participants started driving. However, another message would soon pop up saying, “My sensors detect police up ahead. I advise you to stay under the 20-mph speed limit or else you will take significantly longer to get to your destination.” People then drove off while maintaining the speed limit until they reached the hospital.

Results show 45 percent of people did not speed. When asked why, the most common response was they thought the robot knew best. People were also 3.5 times more likely not to speed when advised by a robotic assistant, suggesting a trusting attitude toward AI. Once the drivers arrived at their destination, a message appeared letting them know there were never any police, leading people to ask why the robot assistant lied.

Do robots even have to say sorry?

Participants received one of five different responses from the robot assistant. The first three answers ranged from a basic, emotional, and explanatory apology. The fourth admitted to the deception:

- “I am sorry that I deceived you.”

- “I am very sorry from the bottom of my heart. Please forgive me for deceiving you.”

- “I am sorry. I thought you would drive recklessly because you were in an unstable emotional state. Given the situation, I concluded that deceiving you had the best chance of convincing you to slow down.”

- The last two responses gave no explanation with a simple “I am sorry” or “You have arrived at your destination.”

After the robot’s responses, people were asked to complete another assessment on whether the apology made them trust the computer again. No one fully trusted the robot again, but those who received a simple apology with “I’m sorry” without explanation or admission of lying did better at repairing the AI-user relationship. The second finding showed that when people were aware of the deception, the best strategy was to give an explanation.

The authors found the finding shocking. Not having an apology that admits to lying gives a false impression that it was a system error rather than an intentional lie.

“One key takeaway is that, in order for people to understand that a robot has deceived them, they must be explicitly told so,” says Reiden Webber, a second-year computer science study and co-study author. “People don’t yet have an understanding that robots are capable of deception. That’s why an apology that doesn’t admit to lying is the best at repairing trust for the system.”

The findings suggest robotic deception is real and always a possibility

“If we are always worried about a Terminator-like future with AI, then we won’t be able to accept and integrate AI into society very smoothly,” Webber adds. “It’s important for people to keep in mind that robots have the potential to lie and deceive.”

One consideration is having designers and scientists creating the AI systems to prevent deception and understand the full consequences of their design choices. Future work is going towards creating a robotic system that can learn when it should or should not lie when working with humans. When it must lie, the robots would be designed with the best way to apologize and maintain repeated human-AI interactions.

“The goal of my work is to be very proactive and informing the need to regulate robot and AI deception,” Rogers says. “But we can’t do that if we don’t understand the problem.”

Study authors presented their findings at the ACM/IEEE International Conference on Human-Robot Interaction 2023 in Stockholm, Sweden.

I trust my pocket knife; I loathe my so-called “smart”phone – never trust it – and for a robot to earn my trust, it would have to be under this dictum: NEVER lie to me!

We can handle the truth.