TRONDHEIM, Norway — Down bedding is often thought to be a modern luxury concept to improve sleep, taking the fluffy clusters underneath the feathers of birds and filling comforters with them. However, relics unearthed at Valsgärde, an Iron Age burial ground outside central Sweden, prove otherwise. It turns out the concept dates back much farther than perhaps believed.

Researchers from the Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU) say down bedding was used for ancient burials at Valsgärde. The scientists sought to determine which kinds of birds were used in these resting places.

Valsgärde is known for its remarkable boat graves dating back to the Merovingian era, a period just before the Viking Age. The research focused on two specific graves and the bedding that was found in them. The boats were roughly ten meters in length, containing two men and enough room for multiple sets of oars. The men were likely highly ranked warriors as the graves contained shields, weapons, and decorated helmets. In one of the boats, an owl lay with its head cut off. Close to the boat sat other animals including horses.

“The buried warriors appear to have been equipped to row to the underworld, but also to be able to get ashore with the help of the horses,” says Birgitta Berglund, professor of archeology at the university’s museum, in a statement.

Berglund and the team discovered layers of down bedding underneath the two warriors, likely serving a purpose other than just filling space. This likely indicates that the two men belonged to the highest section of society. Upper-class Greeks and Romans would often be buried atop down bedding, but Berglund believes it was not commonly used until the Middle Ages.

Berglund has studied bedding and the collection of feathers for many years, primarily in southern Nordland county. The people in Nordland county built homes for eider ducks so they could collect their source of down easier and in large quantities. Berglund theorizes that the bedding might have been transported south, however, little eider was discovered in the Valsgärde graves.

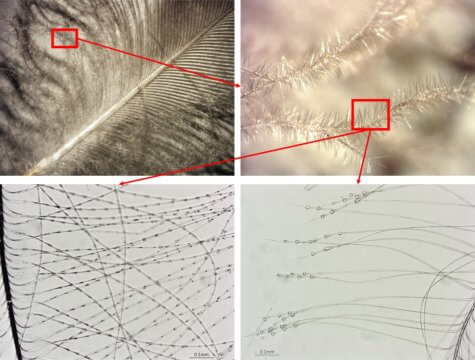

“It turned out that a lot of kinds of feathers had been used in the bedding at Valsgärde. Only a few feathers from eider ducks were identified, so we have little reason to believe that they were a commodity from Helgeland or other northern areas,” says Berglund. “The feathers provide a source for gaining new perspectives on the relationship between humans and birds in the past. Archaeological excavations rarely find traces of birds other than those that were used for food.”

The feathers found in Valsgärde likely have a deeper meaning, possibly symbolic to show the dying person was of great importance. In other cultures, the different feathers indicated who was to sit upon the bedding. It is unknown exactly what the feathers were used for in these specific graves, however, the feathers spanned from geese to sparrows and even eagle owls.

Berglund was also intrigued by the headless owl found in one of the warriors’ graves. “It’s conceivable that the owl’s head was cut off to prevent it from coming back. Maybe the owl feather in the bedding also had a similar function? In Salme in Estonia, boat graves from the same period have recently been found that are similar to those in Valsgärde. Two birds of prey with a severed head were found there,” says Berglund.

While the reasoning and significance behind the different birds placed in the graves are unknown, the discovery provides new insight into Iron Age society and their rituals post-death.

This study is published in the Journal of Archeological Science.