SOUTHAMPTON, United Kingdom — Scientists are showing off the brain of the biggest meat-eating dinosaur that ever lived. An international team created it from the remains of two spinosaur fossils discovered in Surrey and on the Isle of Wight. The predators could reach up to 50 feet in length, weighing around 20 tons. These ferocious beasts hunted in the water as well as on land.

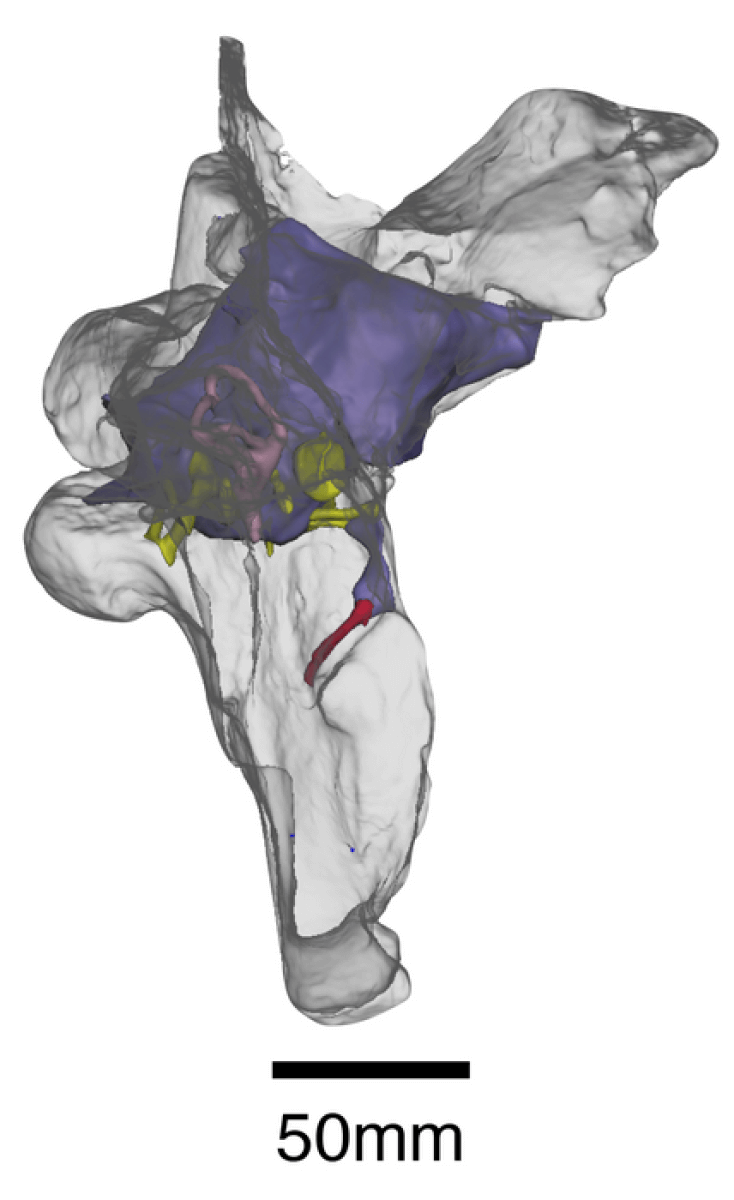

Scientists digitally reconstructed its grey matter and inner ears from the skulls of individuals named Baryonyx and Ceratosuchops. They roamed the region that is now Guildford and Brighstone Bay in the United Kingdom — roughly 125 million years ago. The internal soft tissues controlled coordination, sight, smell, intelligence, and even reproduction. The dinosaur model is providing new insight into the evolution of the biggest land animals that ever lived.

“Despite their unusual ecology, it seems the brains and senses of these early spinosaurs retained many aspects in common with other large-bodied theropods – there is no evidence that their semi-aquatic lifestyles are reflected in the way their brains are organized,” says University of Southampton PhD student and study leader Chris Barker in a media release.

The olfactory bulbs, which process smells, weren’t particularly developed and the ear was attuned to low frequency sounds. Those parts involved in keeping the head stable and the gaze fixed on prey were possibly less developed than in later, more specialized spinosaurs. It suggests that their ancestors already possessed brains and sensory adaptations suited for part-time fish catching. All they needed to do to become specialized for a semi-aquatic existence was evolve an unusual snout and teeth.

Spinosaurs were an unusual type of carnivorous dinosaur that were aquatic as well as terrestrial. They were equipped with long, crocodile-like jaws and six-inch razor-sharp teeth. It enabled them to stalk riverbanks for large fish. This was a very different lifestyle in comparison to the more familiar theropods such as Allosaurus and Tyrannosaurus rex — which these dinosaurs also dwarfed in size.

Baryonyx and Ceratosuchops reached 30 feet long, over 10 feet tall, and weighed about five tons. Ceratosuchops translates as “horned crocodile-faced hell heron,” as it prowled like the wading bird. Its brow was adorned with a series of low horns and bumps.

Baryonyx refers to the animal’s very large claw on its first finger that would have ripped fish to shreds. They were powered by fin-like tails.

Soft organs, such as the brain, don’t survive fossilization. So, the British and U.S. team used CT (computed tomography) scans to peer into perfectly preserved cranial cavities. They isolated sections of the skull, filling the gaps of each. Putting the regions together provided a 3D representation of the space, called an endocast.

“Because the skulls of all spinosaurs are so specialized for fish-catching, it’s surprising to see such ‘non-specialized’ brains,” says contributing author Dr. Darren Naish. “But the results are still significant. It’s exciting to get so much information on sensory abilities – on hearing, sense of smell, balance and so on – from British dinosaurs. Using cutting-edged technology, we basically obtained all the brain-related information we possibly could from these fossils.”

A model of Ceratosuchops’ brain is going on display alongside its bones at Dinosaur Isle Museum in Sandown.

“This new research is just the latest in what amounts to a revolution in paleontology due to advances in CT-based imaging of fossils,” says co-author Lawrence Witmer, a professor of anatomy at the Ohio University Heritage College of Osteopathic Medicine.

“We’re now in a position to be able to assess the cognitive and sensory capabilities of extinct animals and explore how the brain evolved in behaviorally extreme dinosaurs like spinosaurs.”

Analyses have found the bones of Ceratosuchops and its cousin Baryonyx were dense, just like those of today’s penguins, hippos, and alligators. This provided buoyancy, enabling them to submerge themselves while hunting for fish. Animals that find food in water have virtually solid bones. Those of land-dwellers look more like doughnuts, with hollow centers.

“This new study highlights the significant role British fossils have in our constantly evolving, fast-moving understanding of dinosaurs, and shows how the UK – and the University of Southampton in particular – is at the forefront of spinosaur research,” concludes Dr. Neil Gostling, who leads the University of Southampton’s EvoPalaeoLab. “Spinosaurs themselves are one of the most controversial of all dinosaur groups, and this study is a valuable addition to ongoing discussions of their biology and evolution.”

The groundbreaking study is published in the Journal of Anatomy.

South West News Service writer Mark Waghorn contributed to this report.