TOKYO, Japan — The mystery of why babies kick in the womb has finally been solved by scientists.

A team from the University of Tokyo says these random movements help their development. Apparently, they boost the growth of the sensorimotor system, which includes a person’s hand-eye coordination.

Right from birth, and even during pregnancy, infants start to kick, wiggle, and move seemingly without aim or external stimulation. A kick can carry a force of more than 10 pounds and has mystified scientists for centuries. Now, a model shows it helps the infant learn to control its body.

The discovery could lead to new medical treatments

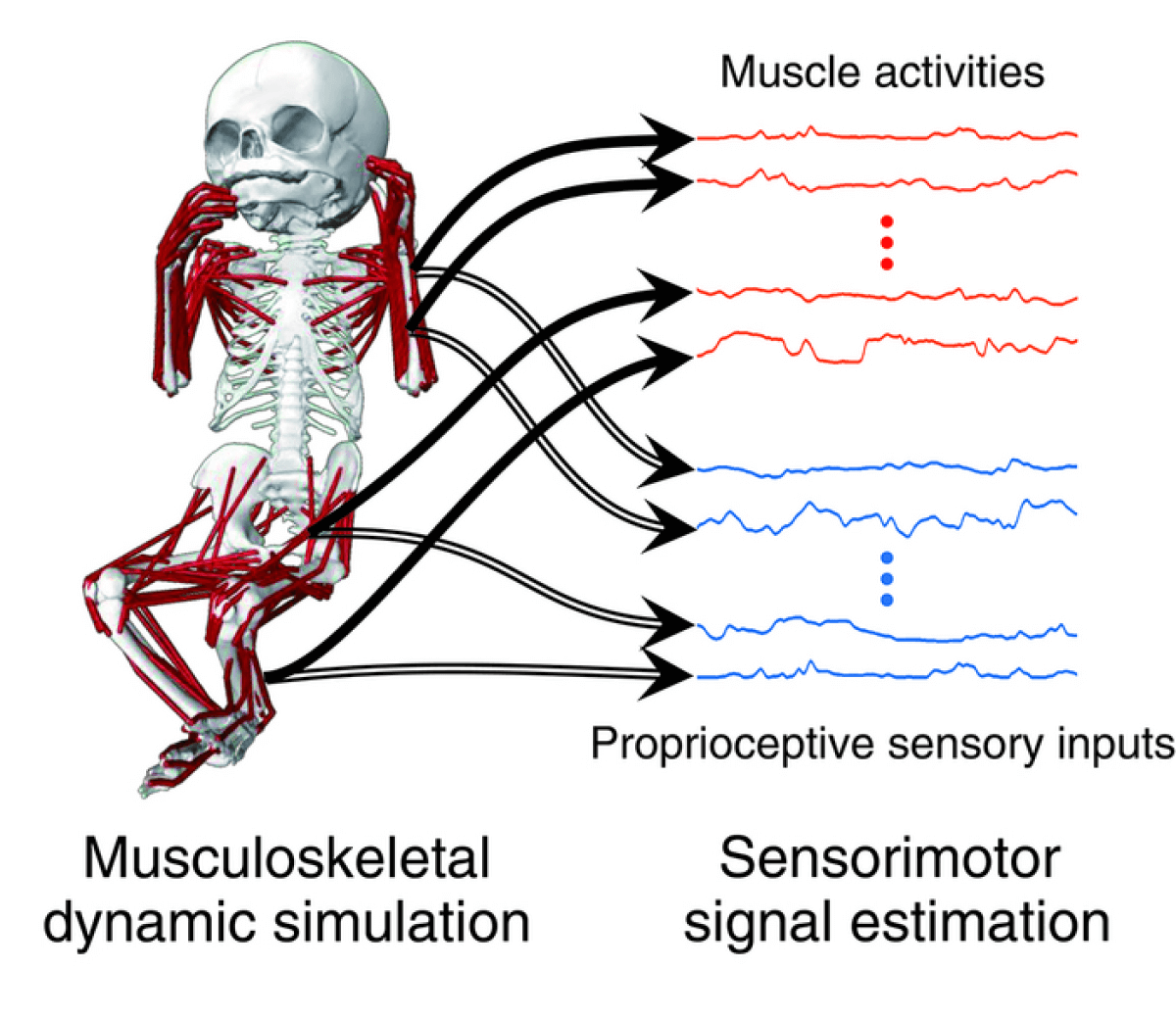

The discovery has implications for medical conditions and developing more agile machines. The Japanese team combined detailed motion capture of newborns and infants with a musculoskeletal computer model. It enabled them to analyze communication among muscles and sensation across the whole body.

They found patterns of muscle interaction developing based on the babies’ random exploratory behavior. It later helped them to perform sequential movements. The discovery could eventually lead to the create of treatments for a host of neurodegenerative disorders. They range from cramps and spasms to multiple sclerosis, spinal cord injuries, motor neuron disease, and even cerebral palsy.

The hundreds of neurons that control each muscle are synchronized in the fetus to create strong contractions that activate “sensors.” Better understanding of the sensorimotor system develops could lead to earlier diagnoses and more effective treatments. Currently, there is limited knowledge about how babies learn to move their body.

“Previous research into sensorimotor development has focused on kinematic properties, muscle activities which cause movement in a joint or a part of the body,” says Project Assistant Professor Hoshinori Kanazawa from the Graduate School of Information Science and Technology, in a university release.

“However, our study focused on muscle activity and sensory input signals for the whole body. By combining a musculoskeletal model and neuroscientific method, we found that spontaneous movements, which seem to have no explicit task or purpose, contribute to coordinated sensorimotor development.”

Babies learn to move by ‘wandering’

The findings are based on recordings of the joint movements of 12 healthy newborns less than 10 days old and 10 young infants who were about three months-old at the time. Muscle activity and sensory input signals were estimated using the infant-scale musculoskeletal computer model of the whole body. Computer algorithms analyzed space and time, or spatiotemporal, features of the interactions.

“We were surprised that during spontaneous movement, infants’ movements ‘wandered’ and they pursued various sensorimotor interactions. We named this phenomenon ‘sensorimotor wandering,’” says Kanazawa.

“It has been commonly assumed that sensorimotor system development generally depends on the occurrence of repeated sensorimotor interactions, meaning the more you do the same action the more likely you are to learn and remember it. However, our results implied that infants develop their own sensorimotor system based on explorational behavior or curiosity, so they are not just repeating the same action but a variety of actions. In addition to this, our findings provide a conceptual linkage between early spontaneous movements and spontaneous neuronal activity.”

When do babies start wandering in the womb?

Previous studies on humans and animals have shown that motor behavior involves a small set of primitive muscular control patterns. They can typically be seen in task-specific or cyclic movements, like walking or reaching.

The latest results support the theory newborns and infants can acquire coordination skills through spontaneous whole-body movements without an explicit purpose or task. Even through “sensorimotor wandering,” the babies showed an increase in coordinated whole-body and anticipatory movements.

Infants showed more common patterns and sequential movements, compared to the random movements of the newborn group. Prof. Kanazawa is now planning to look at how sensorimotor wandering affects later development, such as walking and reaching, along with more complex behaviors and higher cognitive functions.

“My original background is in infant rehabilitation. My big goal through my research is to understand the underlying mechanisms of early motor development and to find knowledge that will help to promote baby development,” Kanazawa concludes.

Most pregnant women begin to feel their baby move between 16 and 24 weeks and the movements can be described as anything from a kick to a flutter, swish, or roll.

The study is published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

South West News Service writer Mark Waghorn contributed to this report.

Professor Kanazawa wonders about higher cognitive functions. I wonder if this prebirth exploration, wandering leads to a motor proprioceptive sense of self.

If this sense of self remains then this Other was there before we were even born.