CHICAGO — Birds fatally flying into the side of glass buildings is nothing new but always tragic. From skyscrapers to giant sports stadiums, the skies are becoming incredibly hazardous for our feathered friends. Although this issue isn’t going away any time soon, scientists are putting the bodies of these dead birds to use in a most unusual way. Researchers at the Field Museum in Chicago examined the final poop these birds carried to make some surprising discoveries about their unique gut health.

Unlike humans, where microbes in the gut have a specific connection to our species, the new study finds the gut makeup of birds is completely different and actually changes from season to season.

“In humans, the gut microbiome—the collection of bacteria, fungi, and other microbes living in our digestive tracts—is incredibly important to our general health and can even influence our behavior. But scientists are still trying to figure out how significant a role the microbiome has with birds,” says Heather Skeen, a research associate at the Field Museum who completed her PhD through the Field and the University of Chicago, in a media release.

What bird microbiomes tell us

The team notes that millions of birds crash into windows while migrating every year. Using DNA sequencing on a whole lot of bird poop from these building collision victims, study authors discovered that their microbes play by a very different set of rules compared to mammals. Normally, the relationship between a mammal’s microbes and the food they eat has continued to evolve over millions of years. For birds, it seems their current environment plays a much bigger role in what scientists find in their stomachs.

“Bird gut microbiomes don’t seem to be as closely tied to host species, so we want to know what does influence them,” Skeen adds. “The goal of this study was to see if bird microbiomes are consistent, or if they change over short time periods.”

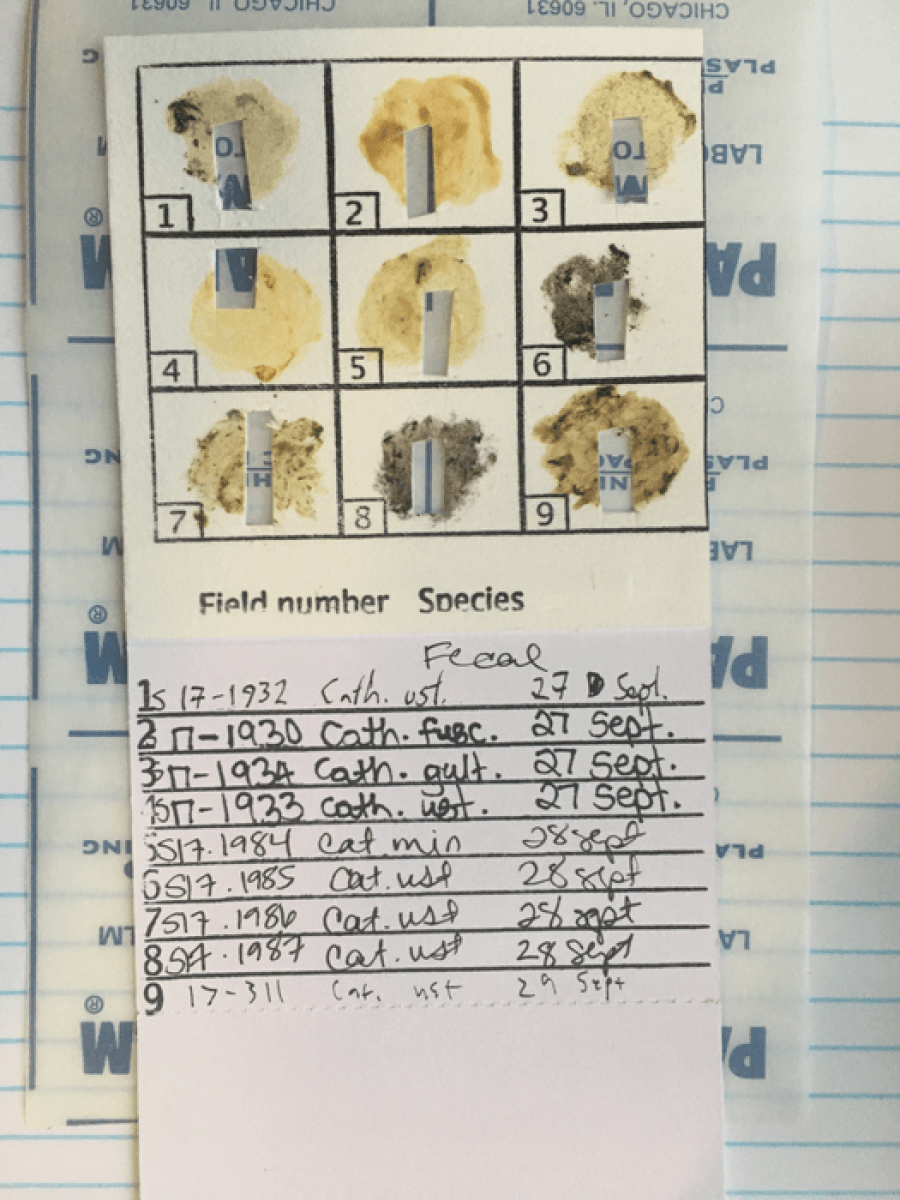

Researchers focused on four common species of songbirds called thrushes during this study. Many of the 747 specimens crashed into Chicago’s buildings, with the others dying closer to their summer breeding grounds in Michigan, Minnesota, and Manitoba. While the DNA sequencing is a pretty high-tech process, getting the bird poop in the first place is a fairly low-tech and disgusting procedure.

“You make a small incision into the abdomen to reach the intestines, and then you squeeze out the contents,” Skeen notes.

Afterwards, they sent the feces off for bacteria classification.

“Analyzing the bacterial DNA present in the poop allowed us to determine exactly what kinds of bacteria were present,” the researcher explains. “It turns out, there were about 27,000 different types of bacteria present.”

Birds microbes vary based on when you find them

Results show, unlike other animals, birds don’t seem to have a microbiome that’s unique to their species. In fact, the bird microbes were different and depended on when and where researchers collected their remains. These microbiomes varied from season to season, year to year, and location to location.

“Across the years, there were fairly significant differences in the composition of the bacteria, which was surprising,” Skeen reports.

“Heather’s research is blowing people’s minds about what a microbiome is or isn’t,” adds Shannon Hackett, associate curator of birds at the Field and a co-author of the paper. “How do birds have functioning immune systems, if their microbiomes change so much in just a few months? It’s hard to weave that into a consistent theory about how they digest food, how they reject parasites, all the things we think of the microbiome doing in humans. How does that work?”

The findings are published in the journal Molecular Ecology.

A correction has been made from a previous version of this story erroneously referring to birds as mammals. The research does compare the microbiome of birds to mammals as noted throughout, however.

“From skyscrapers to giant sports stadiums, the skies are becoming incredibly hazardous for our feathered friends.”

Missing two important points: wind farms are killing birds in greater numbers. Also, domesticated cats kill birds by the tens of millions per year.

Birds are not mammals…

You say in your article “Results show, unlike other mammals, birds don’t seem to have a microbiome…”

It sounds like you are saying birds are mammals. I’m sure you know that birds are not mammals.

Not to nitpick, but at least twice in the article, birds were referred to as “mammals”. They are most assuredly not mammals, as mammals give birth to live young.

To stop birds from flying into your window glass at home

and killing themselves, simply stop cleaning your windows.