CORDOBA, Spain — In a scene out of “Game of Thrones,” it seems that early humans used their peers’ skulls as drinking cups! A new study reveals that cavemen appear to have repurposed human skull caps and transformed bones into tools.

Archaeologists stumbled upon this unsettling discovery while examining deposits from thousands of years ago in a Neolithic cave near Cordoba, Spain. In their findings, they identified a fibula and a shin bone, both modified to serve as tools, and a skull that had been fashioned into a cup. The purpose of these items — whether daily use or ceremonial — is yet to be determined.

The research was conducted by a team from the Universities of Cordoba and Bern in Switzerland. It documented post-mortem bone modifications that were not associated with consumption.

It’s common to find cave bones with marks indicative of human consumption. However, this research reveals how early human societies utilized human bones in unique ways beyond just consumption.

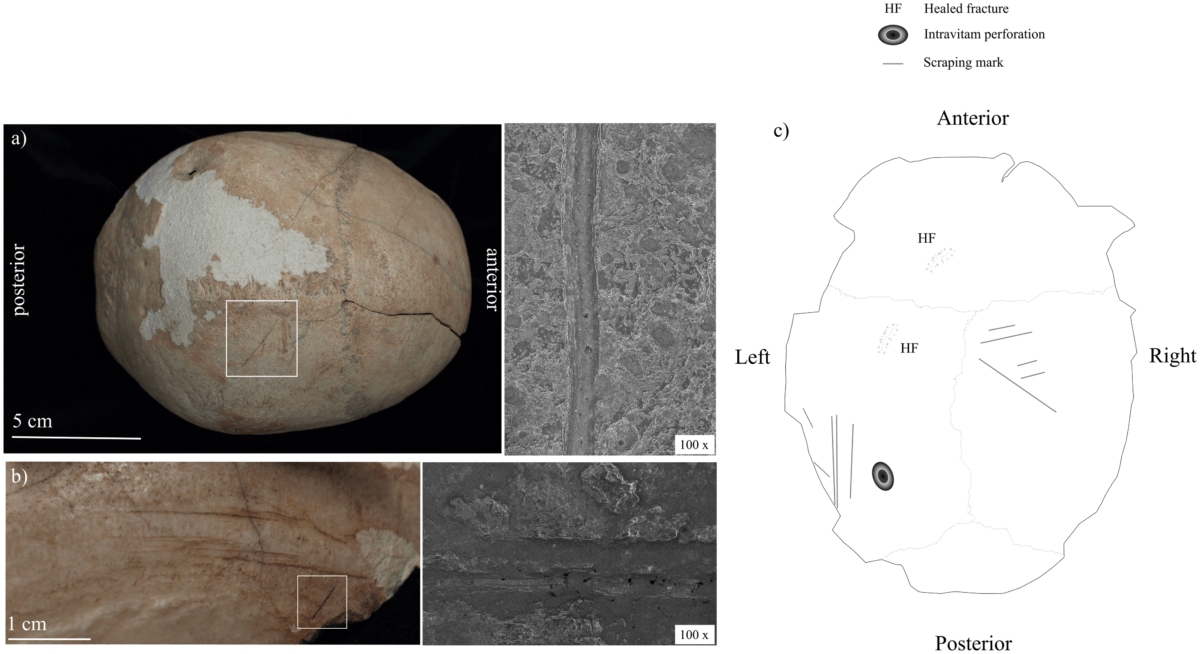

In their study of the Cueva de los Mármoles cave in Priego de Córdoba, the team analyzed over 400 remains of both adults and children. Utilizing an electron microscope, they noted that many marks on the bones were consistent with a cleaning process for tool usage rather than for consumption. These marks don’t imply an attempt to extract soft tissues for eating.

Instead, researchers believe the evidence suggests a meticulous cleaning process aligned with the bones’ use as tools. Among their discoveries were a fibula with a pointed end, a modified shin, and a repurposed skull.

Carbon-14 dating of 12 remains pinpointed three distinct periods of funerary use in the cave: around 3800 BC, 2500 BC, and between 1300 to 1400 BC, during the Bronze Age. The earliest period, the Neolithic, aligns with a surge in the use of megalithic tombs for collective burials.

Coupled with the fact that the bone marks don’t appear to be from consumption, it further supports the theory that these human remains were intentionally shaped for tool usage during specific periods.

“Anthropic traces on the remains (e.g. fresh fractures, marrow canal modifications, and scraping marks) hint at their intentional fragmentation, cleaning from residual soft tissues, and in some cases reutilization,” researchers write in the journal PLoS ONE.

“The repeated pattern, distribution on the cranial vault, and shallow depth of the scraping marks on the ‘skull-cup’ MA-220 indicate an attempt to clean the cranium from residual soft tissues by means of repeated scrapings and the application of a relatively low force.”

“It seems that there was the idea of grouping the dead in the same place, cleaning the remains, and using the bones as instruments, perhaps related to some type of ritual performed inside the cavity,” the Spanish team continues in a statement, according to SWNS.

It seems that the bones were used for ritual and cultural aspects after they were deposited and that these ways of thinking apparently spanned a great period of time, from the end of the Neolithic to the Bronze Age. The fact that the cave was still being used in the Bronze Age is also significant, the team believes.

“This is a time in which we did not expect to find that bodies were still deposited in this cavity,” the researchers conclude.

“These data align with those from other cave contexts from the same geographic region, suggesting the presence, especially during the Neolithic period, of shared ideologies centered on the human body.”

South West News Service writer Jim Leffman contributed to this report.