TOKYO, Japan — Climate change is not only affecting the ocean’s environment, it’s also causing saltwater fish to shrink. Scientists from the University of Tokyo have discovered that fish in the western North Pacific Ocean are getting lighter because the warmer waters are affecting their food supply. This finding has significant implications for the local fishing industry and global seafood markets, as the region is a major contributor to the world’s fish catch.

Researchers analyzed the individual weight and overall biomass of 13 fish species over two critical periods: the 1980s and the 2010s. Their findings indicate that fish weights were lower in both periods compared to other years.

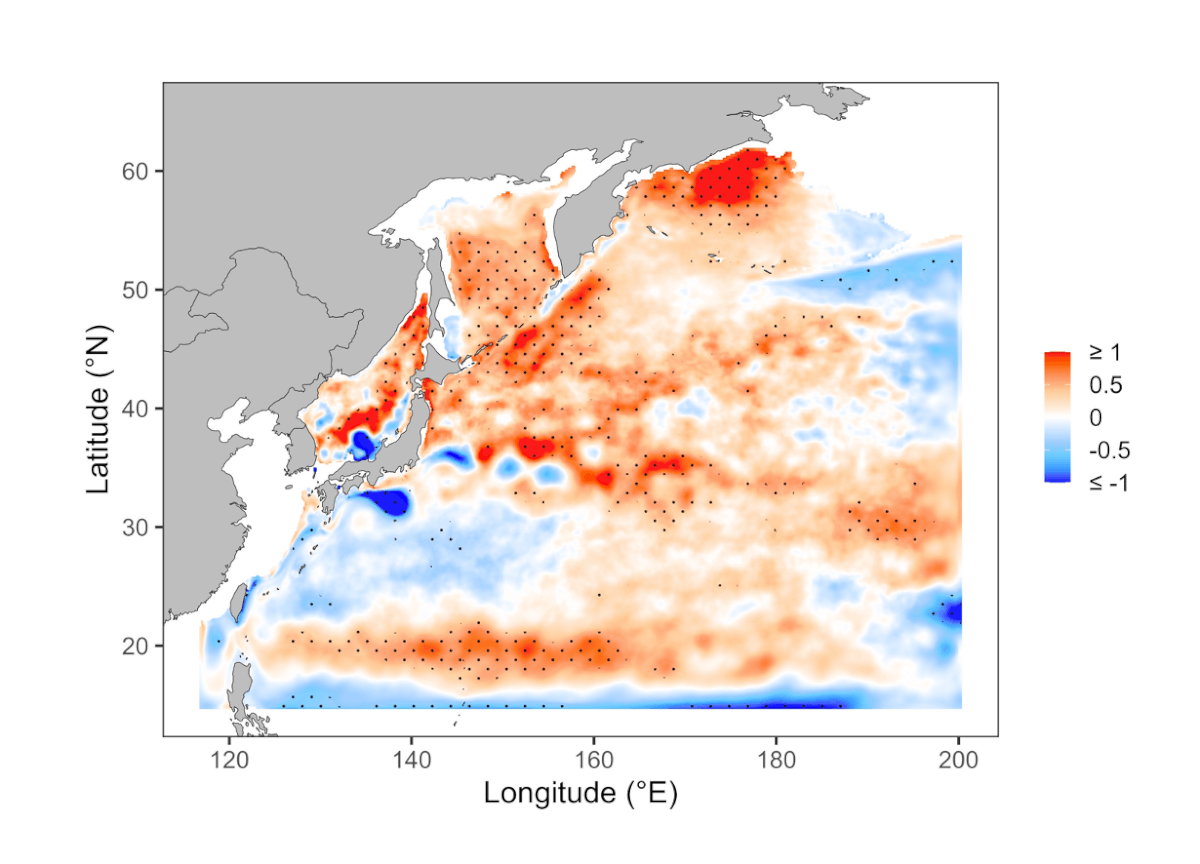

The 1980s saw a decline in fish weight due to an abundance of Japanese sardine, which led to increased competition for food. However, the 2010s experienced a slightly different scenario; although the population of Japanese sardine and chub mackerel rose moderately, the primary concern was the impact of climate change. The warming of ocean waters resulted in a stratification that prevented cooler, nutrient-rich water from rising to the surface, thus limiting the food available to fish.

This phenomenon has broader implications beyond the size of the fish. Japan, known for its rich seafood culture, from sushi to grilled mackerel, is facing a decline in seafood self-sufficiency, grappling with challenges such as reduced sales, labor shortages, and the soaring costs of fisheries management. The study underlines the urgent need for adaptive management strategies in the face of global warming’s escalating impact on marine life.

The western North Pacific, bordering Japan’s eastern coast, is a vital marine area that accounted for almost a quarter of the global total fish caught and sold in 2019, as reported by the U.N. Food and Agriculture Organization. Scientists have shown that fish stocks in this area are not only decreasing in weight but also facing a shift in their ecosystem dynamics.

“With higher temperatures, the ocean’s upper layer becomes more stratified, and previous research has shown that larger plankton are replaced with smaller plankton and less nutritious gelatinous species, such as jellyfish,” says study author Shin-ichi Ito, professor from the Atmosphere and Ocean Research Institute at the University of Tokyo, in a university release.

“Climate change can alter the timing and length of phytoplankton blooms (explosive growth of microscopic algae at the ocean’s surface), which may no longer align with key periods of the fish life cycle. The migration of fish has also been shown to be affected, in other studies, which in turn impacts fish interaction and competition for resources.”

Ito’s team meticulously examined long-term data spanning from 1978 to 2018 for six fish populations from four species, and medium-term data from 1995-97 to 2018 for 17 fish populations from 13 species, alongside seawater temperature data from 1982 to 2014. Their analysis highlights a clear connection between climate change and the marine ecosystem’s health, emphasizing the need for innovative management approaches to sustain fish populations.

The study’s findings serve as a call to action for fishery managers and policymakers. With the mounting effects of climate-induced conditions on fish stocks, traditional management practices may no longer be sufficient.

“Fish stocks should be managed differently than they were before, considering the increasing impact of climate-induced conditions. The situation fish experience is much more severe than decades ago,” concludes Ito. “If we cannot stop global warming, the quality of fish may decline. So, we need to take action so that we can enjoy a healthy ocean and delicious fish.”

The study is published in the journal Fish and Fisheries.

LOL!!! As if….

This article seems more like supposition, without actual facts to back the findings.

Over fishing by the Japanese for decades, could cause smaller fish, due to depletion.

The oceans are inundated with micro plastics that are found in all fish species and in all of the stratified layers from the abyss to the surface. Micro plastics simulate types of phytoestrogens that feminize males, and could definitely cause reproductive stress on the fish population. Before blaming climate change, which is a political hot button, all of the other factors must be considered.