SAN FRANCISCO — Do starfish have a head? For years, researchers thought the answer was no, but a new study finds the entire body of a starfish is essentially one big head! A team in California says this discovery sheds light on the enigmatic evolution of their unique star-shaped structure.

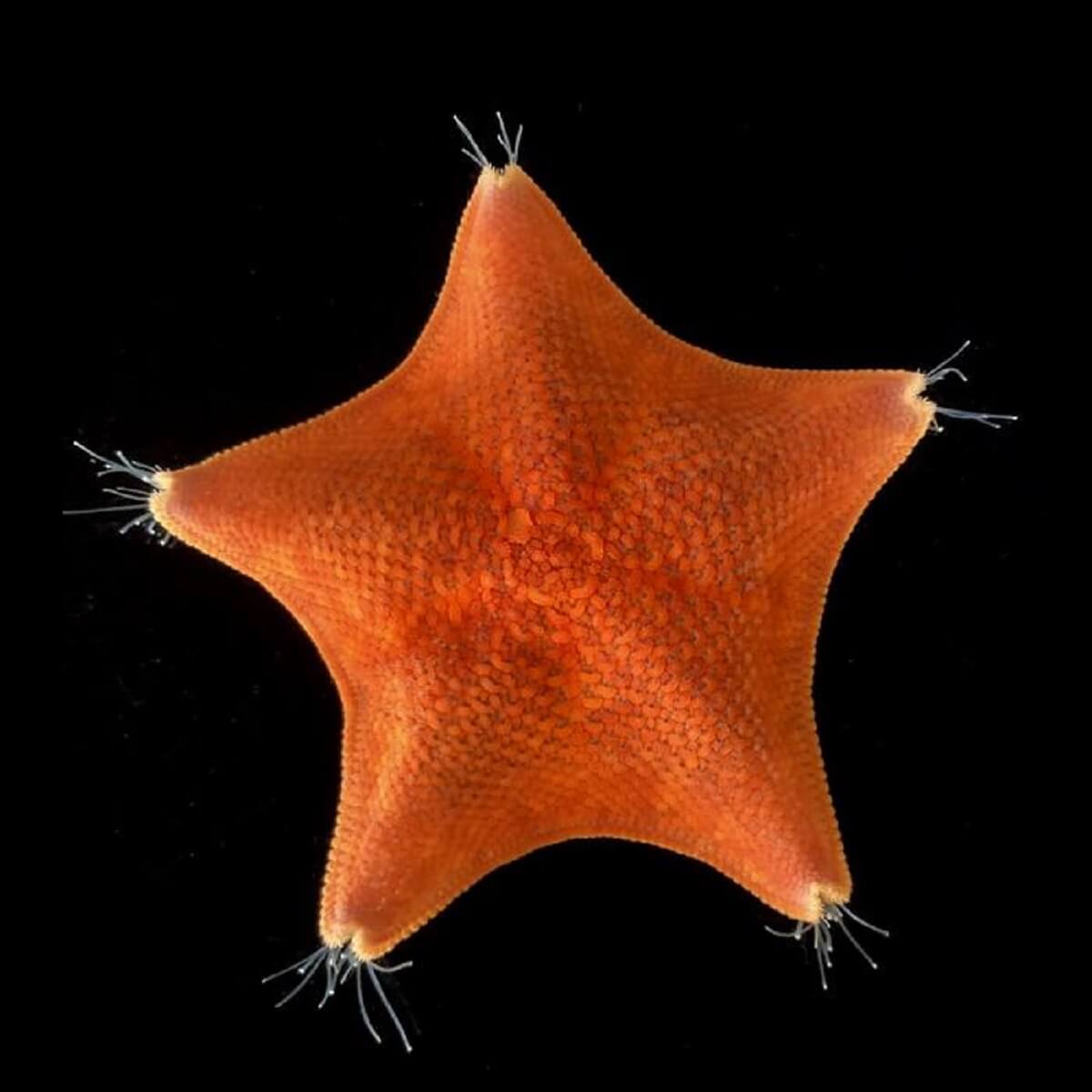

Starfish, also known as sea stars, along with sea urchins and sand dollars, belong to the echinoderms group. These creatures exhibit a distinct “five-fold symmetric” body layout, meaning their body parts are distributed equally into five sections. This structure vastly differs from their bilateral ancestors, who possess mirror-image left and right sides, similar to humans and many other animals.

“How the different body parts of the echinoderms relate to those we see in other animal groups has been a mystery to scientists for as long as we’ve been studying them,” says co-author Dr. Jeff Thompson from the University of Southampton in a media release. “In their bilateral relatives, the body is divided into a head, trunk, and tail. But just looking at a starfish, it’s impossible to see how these sections relate to the bodies of bilateral animals.”

The research — conducted by scientists from Stanford University and UC Berkeley and led by Chan Zuckerberg Biohub San Francisco Investigators — involved comparing the molecular markers of a starfish with other deuterostomes — a broader animal category encompassing both echinoderms and bilateral animals like vertebrates. By analyzing their developmental similarities, the team aimed to unravel the evolutionary process behind echinoderms’ unique body plan.

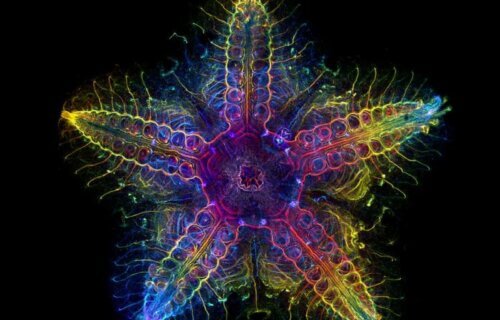

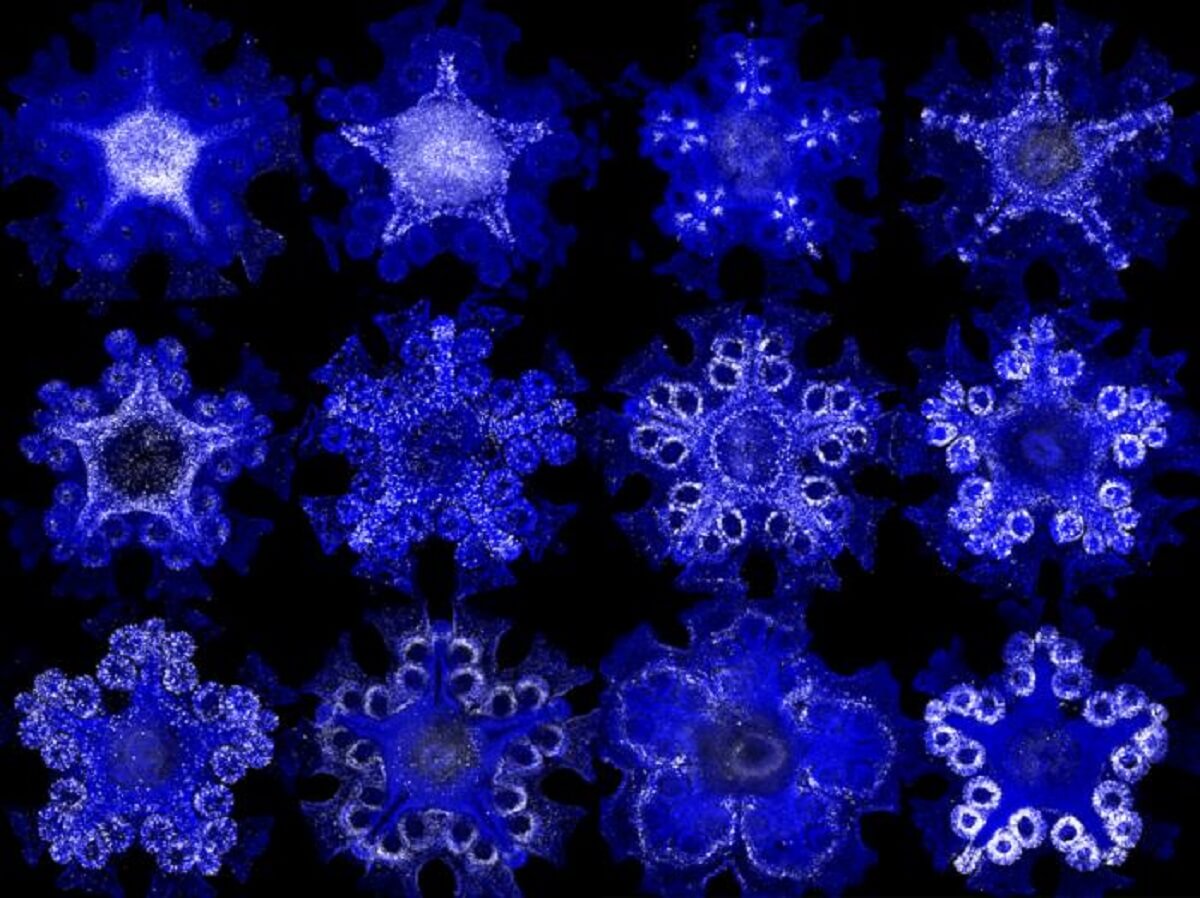

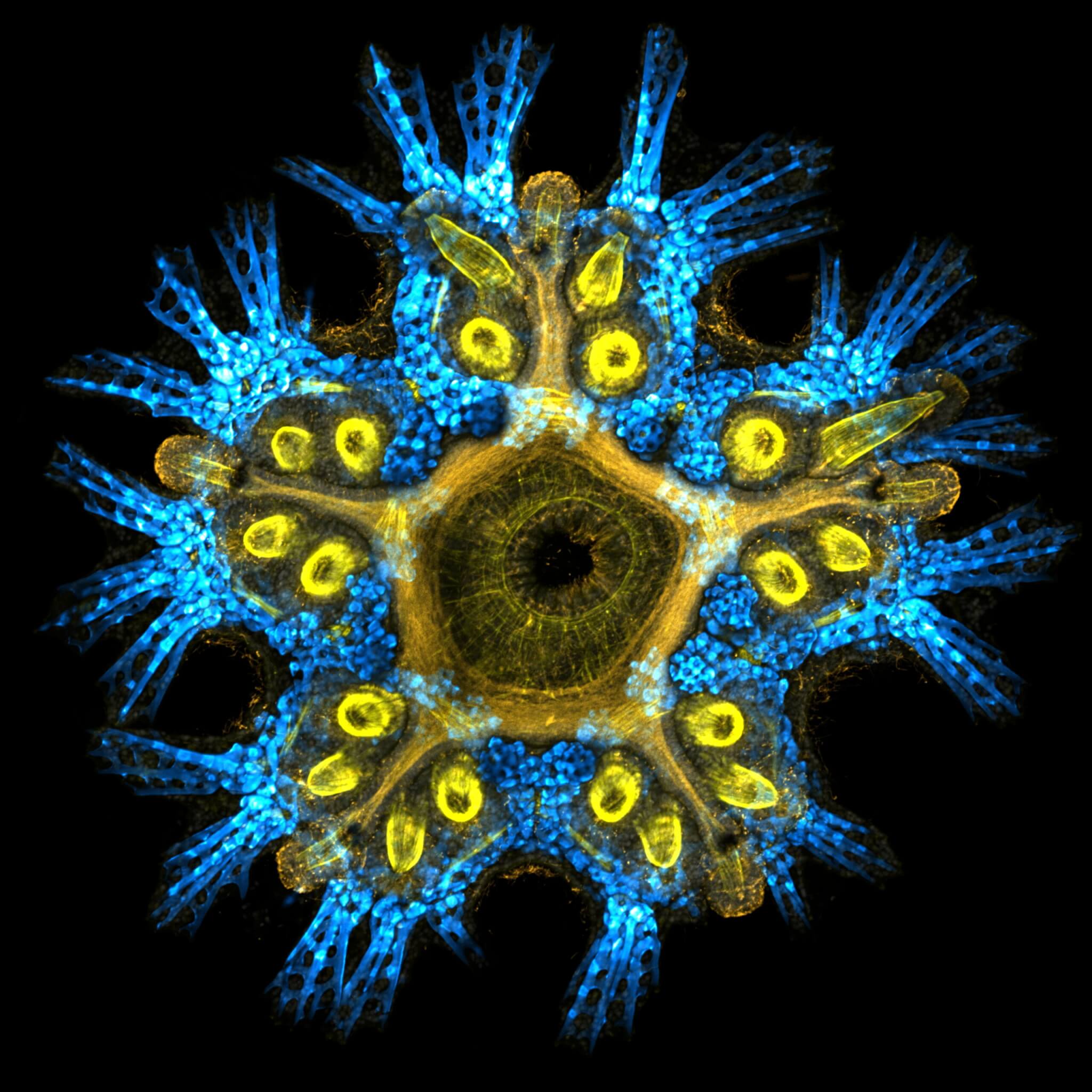

Utilizing advanced micro-CT scanning, an international team meticulously examined the shape and structure of these animals. Meanwhile, U.S. researchers employed techniques like RNA tomography and in situ hybridization to construct a three-dimensional gene expression map in the starfish, pinpointing the specific developmental phases of certain genes.

One focus was on the genes governing the development of the ectoderm, which includes the nervous system and skin and is known to define the anterior-posterior (front-to-back) structure in other deuterostomes. The researchers found that this patterning in starfish correlates with the midline-to-lateral axis of their arms, where the arm’s midline represents the front and the outermost lateral parts resemble the back.

(Credit: Laurent Formery)

“The genes that are typically involved in the patterning of the trunk of the animal weren’t expressed in the ectoderm,” Dr. Thompson explains. “When we compared the expression of genes in a starfish to other groups of animals, like vertebrates, it appeared that a crucial part of the body plan was missing. It seems the whole echinoderm body plan is roughly equivalent to the head in other groups of animals.”

This suggests that starfish and other echinoderms might have evolved their five-section body plan by losing the trunk region of their bilateral ancestors, allowing them to move and feed differently from bilaterally symmetrical animals.

“Our research tells us the echinoderm body plan evolved in a more complex way than previously thought and there is still much to learn about these intriguing creatures. As someone who has studied them for the last 10 years, these findings have radically changed how I think about this group of animals,” Dr. Thompson concludes.

The study is published in the journal Nature.

4 Reasons Starfish Are Vital To Scientific Research

Starfish are fascinating creatures that play an important role in the marine ecosystem. They are also vital to scientific research in a number of ways:

Regeneration

One of the most remarkable things about starfish is their ability to regenerate lost limbs. This process is still not fully understood, but scientists are studying it closely in the hope of developing new treatments for human injuries and diseases.

Immunology

Starfish have a unique immune system that is very different from our own. By studying their immune system, scientists are learning new ways to develop more effective vaccines and treatments for infectious diseases.

Neuroscience

Starfish have a very simple nervous system, but it is still capable of performing some complex tasks, such as navigation and hunting. By studying the starfish nervous system, scientists are learning more about how the human brain works and how to develop new treatments for neurological disorders.

Ecology

Starfish are important predators in the marine ecosystem. They help to control populations of other animals, such as sea urchins and mussels. By studying starfish, scientists are learning more about how marine ecosystems work and how to protect them from threats such as climate change and pollution.

South West News Service writer Stephen Beech contributed to this report.