VENICE — In 2009, the discovery of a 16th-century female skeleton with a brick lodged in its mouth in a Venetian mass grave made global headlines. Dubbed the “Vampire of Venice,” the unusual burial sparked theories about ancient vampire folklore and plague-era superstitions. Now, a new study by Brazilian forensic expert and 3D designer Cicero Moraes and his colleagues has reignited interest in the case, while also drawing criticism from the forensic archaeologist who performed the original facial reconstruction.

When the “Venice Vampire” skeleton (designated “ID6”) was first unearthed, Dr. Matteo Borrini, a forensic anthropologist, was commissioned by National Geographic to reconstruct the woman’s face. Through a painstaking process of analyzing the skull, creating a 3D replica, and applying established tissue depth markers, Dr. Borrini created the plasticine model of the woman’s likeness (seen below), which was later 3D printed and exhibited.

Further studies revealed that the skull belonged to a woman of European ancestry, who died around the age of 61. An analysis of her diet shows she mainly ate grains and vegetables, suggesting she was from Europe’s lower class at the time.

The question of how the brick ended up in the skeleton’s mouth, however, remained a subject of debate. Some archaeologists suggested it may have been placed intentionally as part of a superstitious burial ritual to prevent a suspected “vampire” from rising from the dead. Researchers also theorized that a gravedigger may have wedged a rock between the corpse’s teeth to prevent the alleged vampire from chewing through her shroud and infecting others with the plague. Others argued the brick could have ended up there by chance, and that more evidence was needed to support claims of intentional placement.

Enter Moraes and his team, who set out to test whether it was physically possible to insert a brick into a corpse’s mouth without damaging the teeth or jaw. To investigate this, they employed a multi-pronged approach combining digital modeling, practical experimentation, and data from the original archaeological reports.

First, Moraes created a 3D digital model of the ID6 skull using measurements and images from Dr. Borrini’s published work and online sources. While not having direct access to the original remains, the team aimed to create a reasonably accurate digital replica to serve as a basis for their experiments. Next, they simulated the insertion of a virtual brick into the digital skull’s mouth, carefully noting any potential points of contact or resistance. This allowed them to assess the feasibility of placing a brick postmortem without causing osteological damage.

To validate their digital findings, Moraes and his team also conducted practical experiments using a real human skull. They created a physical brick with dimensions matching those reported for the ID6 skeleton and attempted to place it in the skull’s mouth, documenting the process and any resulting interactions with the teeth and jaw.

“A test was performed with the specimen, inserting it into the oral cavity and analyzing the structural deformation of the skin, as well as the rotation of the mandible,” Moraes and the team explain in their report in the journal OrtogOnline.

Combining insights from both the digital and physical experiments, Moraes’ study concluded that it is indeed possible to insert a brick into a corpse’s mouth without damaging the skeletal structures, particularly if done before the onset of rigor mortis. These findings lend credence to the theory that the brick in the “Vampire of Venice” burial may have been placed intentionally, although they do not definitively prove it.

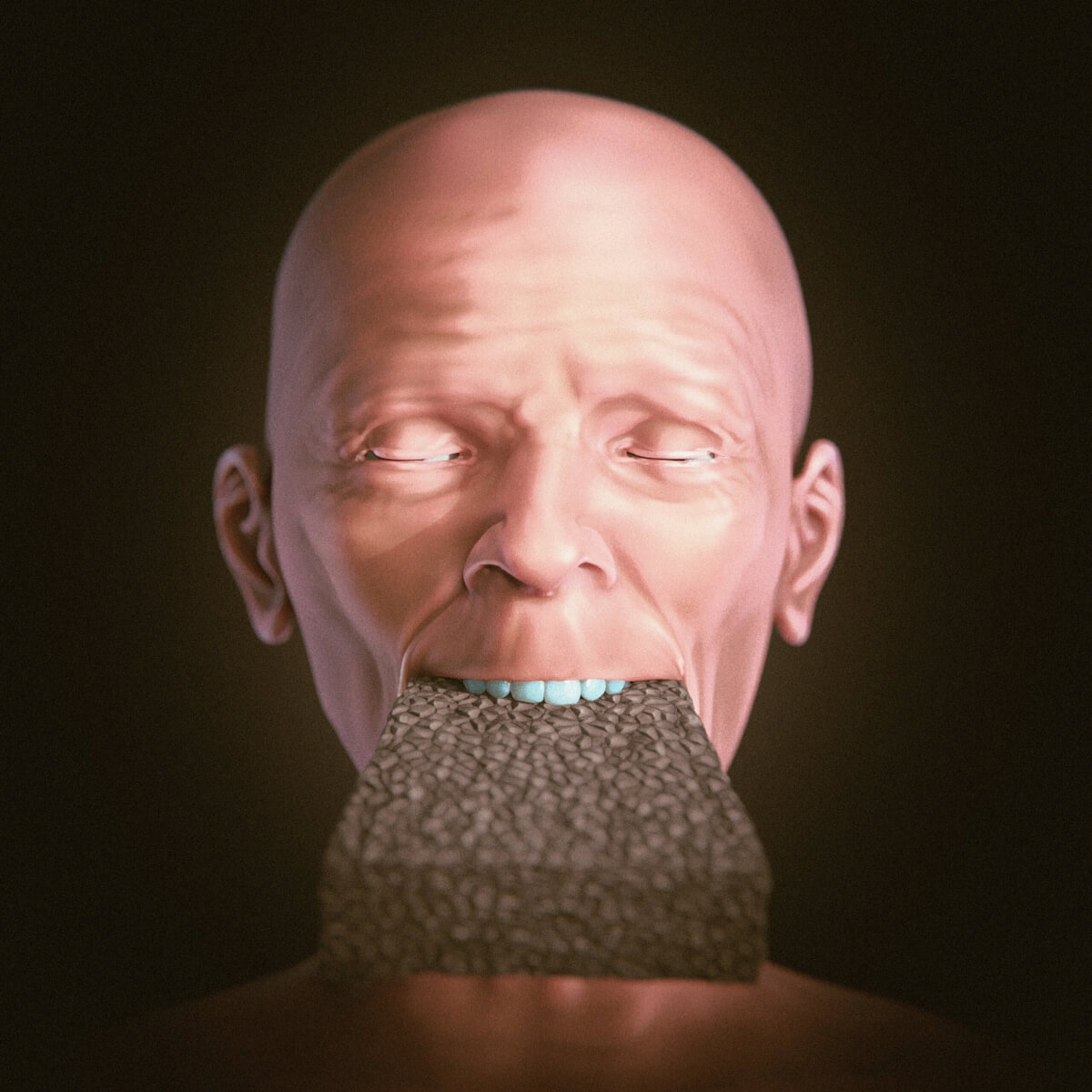

Moraes’ team also conducted a facial reconstruction of their own, using a novel “anatomical deformation” technique. Starting with a CT scan of a different individual, they digitally deformed the skull to match the morphological characteristics of the ID6 skeleton. They then used this deformed skull as the basis for reconstructing the facial features, employing a combination of digital sculpting, tissue depth markers, and anatomical references.

While this innovative approach allowed Moraes to create a lifelike 3D rendering of the “Vampire’s” face, it has drawn criticism from Dr. Borrini and other experts in forensic facial reconstruction. They argue that this method, while visually impressive, lacks the scientific rigor of traditional reconstructions based on direct analysis of the original skeletal remains.

“The portrait suggested by Mr. Moraes is far from any scientific reconstruction, considering that he never had access to the original remains, neither to a copy nor the digital model. I never shared any data with him,” Dr. Borrini tells StudyFinds. “In addition, Mr. Moraes used a ‘skull of the virtual donor from a computed tomography was imported and adjusted to fit the references.’ This is not science fiction or bad science: it is not science at all. It is like someone printing a picture of the Moon from the NASA website, putting it on the floor, stepping on it, and claiming that he walked on the Moon.”

Dr. Borrini stresses that his own reconstruction, grounded in hands-on examination of the ID6 skeleton and adherence to established forensic protocols, remains the most scientifically valid depiction of the individual’s appearance.

“Forensic facial reconstruction is a specialized technique that forensic anthropologists can adopt to help judicial authorities in cases of missing people or unknown bodies,” Borrini explains. “It is a scientific discipline designed to provide justice to victims and their families. It is a serious and rigorous procedure that, in some cases, can be applied in archaeological and historical contexts, as I have done for the ‘Venice Vampire’ in 2009. As in that case, it has to be done according to science. Everything else is… something very different.”

The debate surrounding Moraes’ study underscores the ongoing challenges and fascination of investigating historical cold cases like the “Vampire of Venice.” While new technologies and innovative approaches can offer fresh perspectives, it’s crucial that they be balanced with respect for established scientific methodologies and the limitations of working with fragmentary evidence.

Ultimately, the enduring legacy of the “Vampire of Venice” may lie not in definitively solving the mystery of her burial, but in the way her story continues to inspire scientific inquiry, challenge our assumptions, and spark the imagination across centuries. As archaeologists, anthropologists, and forensic scientists continue to pore over her remains and their context, we may slowly piece together a clearer picture of her life, death, and the beliefs of her time – a testament to the power of multidisciplinary collaboration and the enduring human fascination with the secrets of the past.

StudyFinds’ Editor-in-Chief Steve Fink contributed to this report.

Dear Editor,

I would like to thank you for writing the article about the vampire. I would like to clarify the situation involving Dr. Borrini’s criticism. Unfortunately he has shared incorrect information, even though I have explained the technique and published the detailed step-by-step guide. As he ignored my contact, I had to write a public note and the document is here:

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/379248836_The_Controversy_Surrounding_the_New_Facial_Approximation_of_the_Vampire_of_Venice_-_Nuovo_Lazzaretto.

I would like, if possible, you calmly to read it and, if possible again, consider it a note on the story.

Yours sincerely