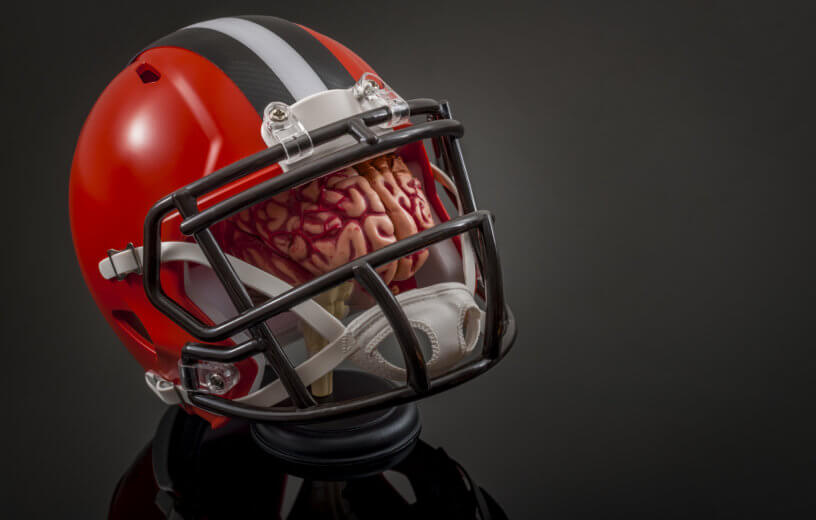

BOSTON — It’s become glaringly apparent in recent years that head trauma in contact sports like football is a much bigger health concern than many believed decades ago. The progressive and fatal brain disease CTE (chronic traumatic encephalopathy) reportedly has a strong link to contact sports, but does a football player’s number of concussions actually drive their risk of developing the condition? While concussions are almost certainly involved, researchers in Boston suggest that the relationship between CTE and football isn’t so simple.

With the NFL season fast approaching, researchers report number of diagnosed concussions alone is not associated with CTE risk. Instead, players’ odds of developing CTE were related to how many head impacts they received as well as how hard those head impacts were. These findings are based on an analysis of 631 deceased football players, considered the largest CTE study to date, conducted by researchers at Mass General Brigham, Harvard Medical School, and Boston University.

Study authors utilized an innovative new tool called a positional exposure matrix (PEM) to synthesize data from 34 independent studies. This helped them estimate the number and severity of football players’ head impacts over the course of their careers.

“These results provide added evidence that repeated non-concussive head injuries are a major driver of CTE pathology rather than symptomatic concussions, as the medical and lay literature often suggests,” comments study senior author Jesse Mez, MD, MS, Associate Professor at the BU Chobanian and Avedisian School of Medicine and Co-Director of Clinical Research at the BU CTE Center.

This new work could provide football with a “playbook” of sorts to help prevent CTE in current and future players, researchers believe.

“This study suggests that we could reduce CTE risk through changes to how football players practice and play,” says lead study author Dan Daneshvar, MD, PhD, Assistant Professor at Harvard Medical School and Physician at Mass General Brigham affiliate Spaulding Rehabilitation, in a media release. “If we cut both the number of head impacts and the force of those hits in practice and games, we could lower the odds that athletes develop CTE.”

The research team used their new PEM tool to calculate a rough estimate of the cumulative number of head impacts, and the cumulative linear and rotational accelerations associated with those impacts, all based on the levels and positions athletes played during their football careers. This led to the discovery that cumulative repetitive head impact (RHI) exposure was associated with CTE status, CTE severity, and pathologic burden.

Moreover, the study reports that models using the intensity of impacts were better at predicting CTE status and severity than other models that used solely duration of play or number of hits to the head. All in all, the research team calls the PEM a valuable tool that can help improve further studies on the risks of playing football. For instance, the PEM could be used in future studies to assess other potential effects of RHI exposure beyond CTE. This would help modern medicine cultivate a clearer understanding of the specific types of RHI most likely to cause these problems.

“Although this study was limited to football players, it also provides insight into the impact characteristics most responsible for CTE pathology outside of football, because your brain doesn’t care what hits it,” Prof. Daneshvar concludes. “The finding that estimated lifetime force was related to CTE in football players likely holds true for other contact sports, military exposure, or domestic violence.”

Study authors point to a limitation of their work; this study used a convenience sample of football-playing brain donors who generally tended to have higher exposure to RHI than the general population of football players. However, a significant number of donors also had lower exposures, so researchers believe these findings can still be extrapolated to most football players.

The study is published in the journal Nature Communications.

You might also be interested in:

- Youth tackle football connected to permanent brain damage, early decline

- Playing tackle football before age 12 leads to CTE symptoms much earlier

- Head injuries could quadruple the risk of developing cancerous brain tumors