UNIVERSITY PARK, Pa. — Giraffes are even more endangered than conservationists previously believed, a new study warns. While some may think the problem may be predators in the wild or a lack of tall trees to snack on, researchers in Pennsylvania say these creatures are dying out due to their inability to climb up steep slopes.

The study found that Masai giraffes, separated geographically by the Great Rift Valley in East Africa, have not interbred or exchanged genetic material in more than a thousand years. In some cases, it’s been hundreds of thousands of years. The researchers suggest that these two populations should be treated separately for conservation purposes, advocating for distinct but coordinated conservation efforts.

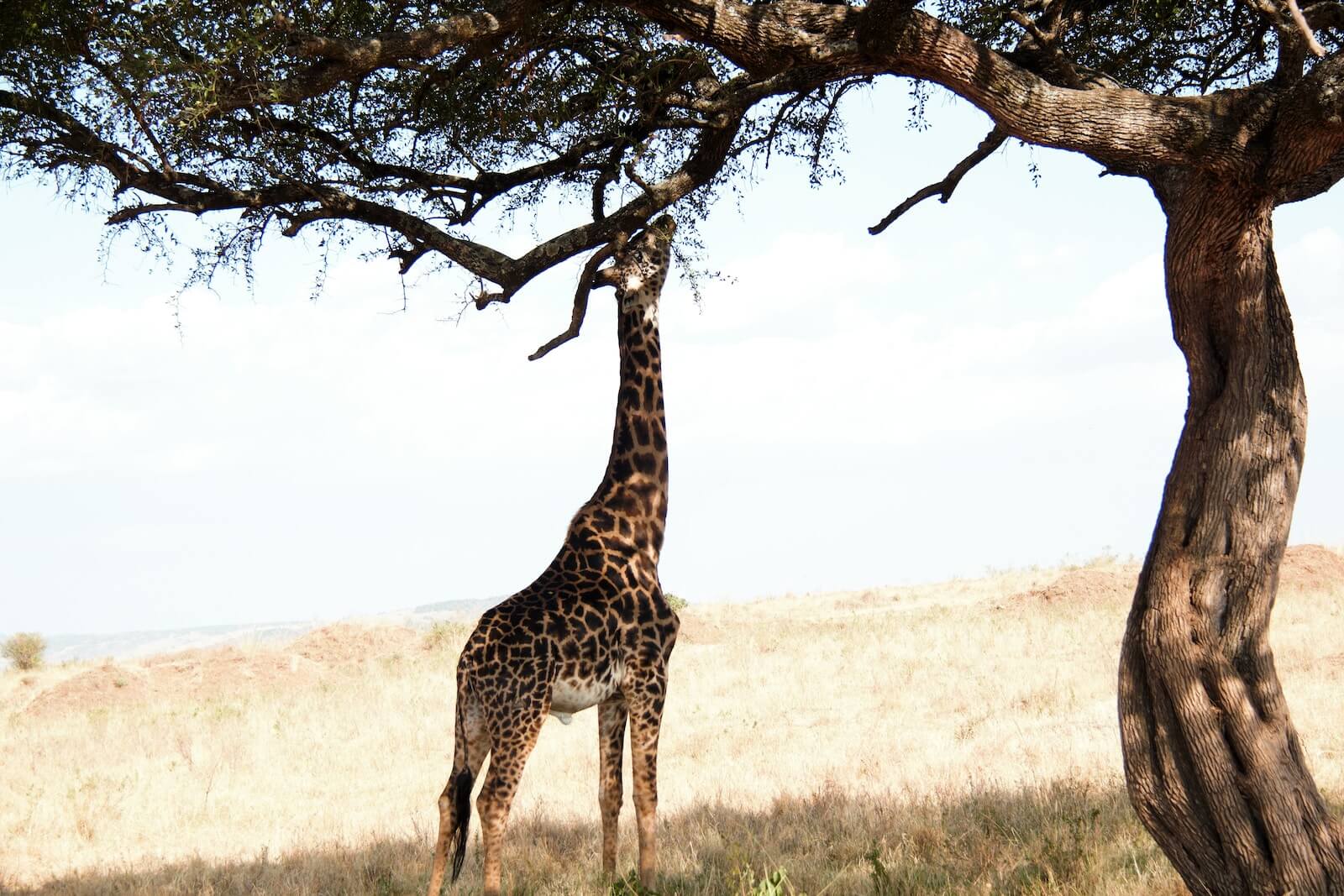

Over the past 30 years, the population of giraffes has declined precipitously, leaving fewer than 100,000 individuals worldwide. Masai giraffes, a species endemic to Tanzania and southern Kenya, have experienced about a 50-percent decline in population during this period. The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) classifies them as endangered. Factors such as illegal hunting and increasing human encroachment on their habitat have contributed to this decline, leaving approximately only 35,000 individuals remaining.

“The habitat of Masai giraffes is highly fragmented, in part due to the rapid expansion of the human population in east Africa in the last 30 years and the consequent loss of wildlife habitats,” says Douglas Cavener, the Dorothy Foehr Huck and J. Lloyd Huck Distinguished Chair in Evolutionary Genetics and professor of biology at Penn State.

“Additionally, the Great Rift Valley cuts down through East Africa, and the steep slopes of its escarpments are formidable barriers to wildlife migration. We looked at the genomes of 100 Masai giraffes to determine if populations on either side of the rift have crossed over to breed with each other in the recent past, which has important implications for conservation,” the research leader adds in a university release.

Giraffes are notoriously bad climbers, the Penn State team explains. Using satellite data, they found just two locations where the angle of the rift’s slopes were shallow enough for the species to potentially climb over. However, there were no actual reports of the giraffes doing so.

To better understand the exchange of genetic information throughout history, study authors used a mix of whole genome sequencing of the nuclear genome — genetic information coming from both parents — and the mitochondrial genome, which includes genes coming only from the animal’s mother.

“Interbreeding among different populations results in the exchange of genetic information — often called gene flow — and is generally considered to be beneficial because it can improve overall genetic diversity and help buffer small populations against disease and other threats,” says Lan Wu-Cavener, assistant research professor of biology and a member of the research team.

“To understand potential gene flow across the rift, we sequenced the more than 2 billion base pairs that make up entire nuclear genome as well as the more than 16,000 base pairs that make up the entire mitochondrial genome. This complex data presented a variety of computational and data storage challenges for our small team, but using the entire genome instead of a small portion allowed us to definitively investigate the extent of gene flow among these populations.”

Results revealed several blocks of genes within the mitochondrial genome that giraffes typically inherit together (haplotypes) across the two populations. The team conducted an analysis based on patterns of similarity across those haplotypes.

Study authors discovered giraffes on the east side of the rift did not have any overlapping haplotypes with giraffes from the west side of the rift. This suggests that female giraffes have not migrated across the rift to breed in the past 250,000 to 300,000 years.

“Female-mediated gene flow between the two populations has not occurred in hundreds of thousands of years, or probably ever,” Cavener continues. “This raised a new question that we hadn’t anticipated about the origin of these populations. We originally thought that one population was founded and then some individuals crossed over to the other side of the rift to establish the second population. But we now think that the two populations were founded independently more than 200,000 years ago.”

The nuclear genome suggests that gene flow through the movement of male giraffes may have occurred around 1,000 years ago. The team plans to take samples from additional animals from both populations to better understand when and why this gene flow stopped.

“Taken together, these results suggest that populations of giraffes on each side of the rift are genetically distinct, with each population having less genetic diversity than if they were one, larger interconnected population,” Cavener adds.

“There are very little prospects of giraffes crossing over the rift on their own, and translocation is highly impractical with giraffes. This suggests that Masai giraffes are more endangered than we previously thought, and that conservation efforts for each population should be considered in an independent but coordinated fashion. We hope that the Tanzanian and Kenyan governments will increase the protection of Masai giraffes and their habitats, especially given the recent increase in giraffe poaching in the area.”

The research team, whose results are published in the journal Ecology and Evolution, also discovered alarmingly high indicators of inbreeding on both the east and west sides of the rift. Inbreeding is a process that diminishes genetic diversity and the overall fitness of a population.

The researchers aim to further study the populations of Masai giraffes on both sides of the rift, particularly those that are extremely isolated, to more comprehensively understand the risks posed by inbreeding.

Additionally, the team intends to explore how giraffes move between groups on the east side of the rift, where the habitat is notably fragmented. This research aims to better understand how to prioritize conservation efforts to maintain connectivity among these fragmented populations.

“We would also like to use genetics to clarify parental and sibling relationships in Masai giraffes,” Cavener concludes. “There’s a lot we don’t know about how giraffes mate, for example do only a few males successfully breed in a local population over many years or do several males breed in that population? These questions are critically important to estimating the actual breeding population of the populations and will continue to guide our efforts to protect and conserve these majestic and charismatic animals.”

South West News Service writer Stephen Beech contributed to this report.