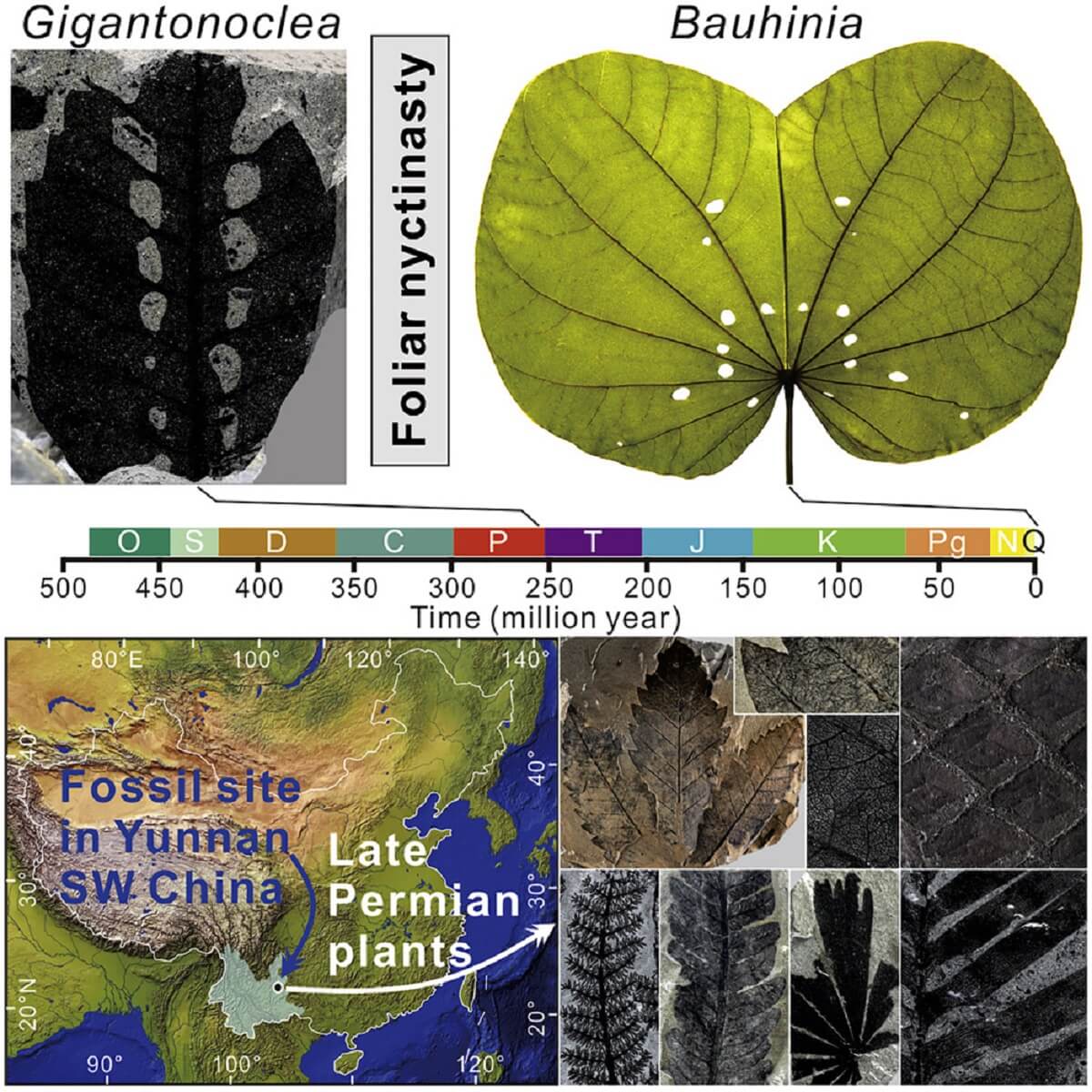

KUNMING, China — Researchers have discovered signs of insect bites on plants that date back over 250 million years, marking leaf sleep movement at night. This occurrence pre-dates even the age of dinosaurs.

“Our findings reveal extinct plants evolved foliar nyctinastic movements at such an early stage of plant evolution, which is surprising to me,” says Professor Zhuo Feng, the study’s lead author from Yunnan University in China, in a media release.

Ancient grasshoppers might have left the bite marks, some of the earliest known chewing insects, which are notorious pests of cereals, vegetables, and pastures, feeding both day and night.

“Since it is impossible to tell whether a folded leaf found in the fossil record was closed because it experienced sleeping behavior or because it shriveled and bent after death, we looked for insect damage patterns that are unique to plants with nyctinastic behavior,” says co-author Dr. Stephen McLoughlin from the Swedish Museum of Natural History in Stockholm. “We found one group of fossil plants that reveals a very ancient origin for this behavioral strategy.”

Leaves typically lower or spread during the day for moisture absorption or rain catchment, and fold inward at night to store it, preventing evaporation. This is the time when insects are most likely to feed, creating symmetrical bite marks on folded leaves, notes Prof. Feng.

The research team examined gigantopterids, an extinct seed-producing group characteristic of the Permian Cathaysian floras that lived roughly 300 to 250 million years ago. The broad leaves of these plants were frequently attacked by insects, leaving easily identifiable damage.

“I was surprised by the distinctive pattern of the insect damage and thought it might represent foliar nyctinasty in the fossil plant,” says Prof. Feng. “But to be sure, I searched for more fossil evidence to reinforce my assumption. The second fossil specimen—a different species of the same plant group—revealed the same insect-feeding damage as that preserved in the leaf collected two years earlier. I then began to think about the scientific significance of the specimens.”

Upon examining hundreds of specimens from the Xishuangbanna Tropical Botanical Garden, he found further supportive evidence. These findings illuminate the ecology and history of plants.

“In recent years, some [gigantopterids] have been found to possess hooks on their leaves and have specialized water-conducting cells that indicate that at least some were climbers within early rainforest-like ecosystems,” McLoughlin says. “To this we can now add that some of these plants folded their leaves on a daily basis.”

“It is now clear that sleeping behavior has evolved independently in various plant groups and at different times in the course of Earth’s history, so it must have some ecological benefits to the parent plant,” McLoughlin continues.

He believes that future detailed observations of animal interactions with fossils could help decipher the biological features of ancient organisms.

“Evidence of fossil insect damage on leaves can provide a great deal more information about plant ‘behavior’ and ecology than just herbivory,” McLoughlin explains. “The fossil record of plant-animal interactions is a rich and largely untouched bank of ecological data.”

Feng concludes that scientists now know that “the evolutionary history of the ‘sleeping movements’ of leaves can be traced back to the late Paleozoic gigantopterid plants more than 250 million years ago.”

The researchers plan to investigate other plant species that may have exhibited similar behavior.

The study is published in the journal Current Biology.

You might also be interested in:

- Largest fossilized flower preserved in amber could be nearly 40 million years-old!

- Origins of flowers traced back to fossilized plants from 126 million years ago

- Sexy perfume from engineered plants could replace common pesticides, study explains

South West News Service writer Stephen Beech contributed to this report.