GENEVA, Switzerland — As we age, cognitive decline is more likely to develop. So, how can we train our brain to fight it? Researchers from the University of Geneva (UNIGE), HES-SO Geneva, and EPFL say the answer may be hiding in music. Their study finds that both listening and learning to play music could prevent a decline in brain health.

Leading up to cognitive decline, the brain loses its “plasticity,” as well as gray matter, which holds the neurons that keep the brain sharp. Once this decline starts, working memory is the hardest to maintain. This type of memory includes things like recalling a phone number long enough to jot it down on paper, or language translations. The researchers studied how practicing music could combat this degradation using 132 healthy older and retired adults between the ages of 62 and 78. Importantly, all of these participants never took musical lessons for more than six months in their lifetime.

‘‘We wanted people whose brains did not yet show any traces of plasticity linked to musical learning. Indeed, even a brief learning experience in the course of one’s life can leave imprints on the brain, which would have biased our results,’’ explains Damien Marie, first author of the study and a research associate at the CIBM Center for Biomedical Imaging, the Faculty of Medicine and the Interfaculty Center for Affective Sciences (CISA) of UNIGE, and the Geneva School of Health Sciences, in a university release.

Study authors split the participants randomly into two classes, piano playing and musical awareness. For the latter, participants had to actively listen and focus on instrument recognition and analysis of musical properties across different musical styles. Both classes were an hour long and each class had 30 minutes of homework daily.

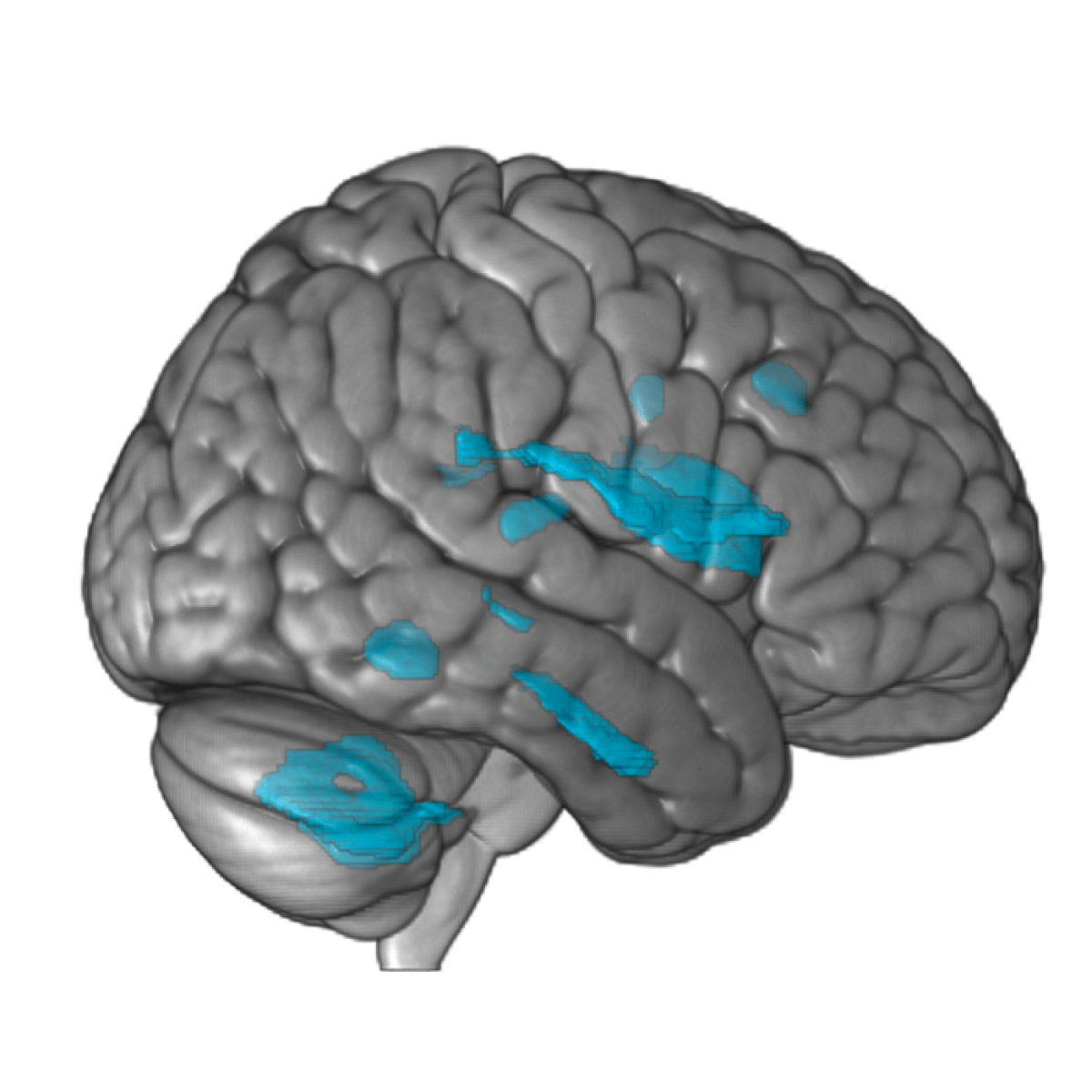

‘‘After six months, we found common effects for both interventions. Neuroimaging revealed an increase in grey matter in four brain regions involved in high-level cognitive functioning in all participants, including cerebellum areas involved in working memory. Their performance increased by 6% and this result was directly correlated to the plasticity of the cerebellum,’’ says study author Clara James, a lecturer at the Faculty of Psychology and Educational Sciences of UNIGE and full professor at the Geneva School of Health Sciences.

Further, sleep quality, the number of lessons followed over the intervention course, and the daily training quantity, all positively impacted the improvements noted. The team did note that the grey matter in the right primary auditory cortex — an area of the brain that processes sound — remained stable in pianists. In the active listening group, it went down.

‘‘In addition, a global brain pattern of atrophy was present in all participants. Therefore, we cannot conclude that musical interventions rejuvenate the brain. They only prevent ageing in specific regions,’’ says Marie.

Overall, the results show that listening and practicing music can preserve cognition. This is welcoming news, considering that so many people around the world enjoy music. The study authors now emphasize the inclusion of these activities in policy for healthy aging. Looking ahead, they plan to evaluate the potential of music in those with mild cognitive impairment, which is the grey area between normal aging and dementia.

The findings appear in the journal NeuroImage.