OKINAWA, Japan — Nemo may have been an innocent and peaceful little fish in the animated classic, but a new study finds real clownfish are both feisty and territorial — and more importantly, they can count! Researchers in Japan say the territorial species counts to distinguish between friends and foes, examining the stripes on the bodies of intruders and cohabitants entering their ocean homes.

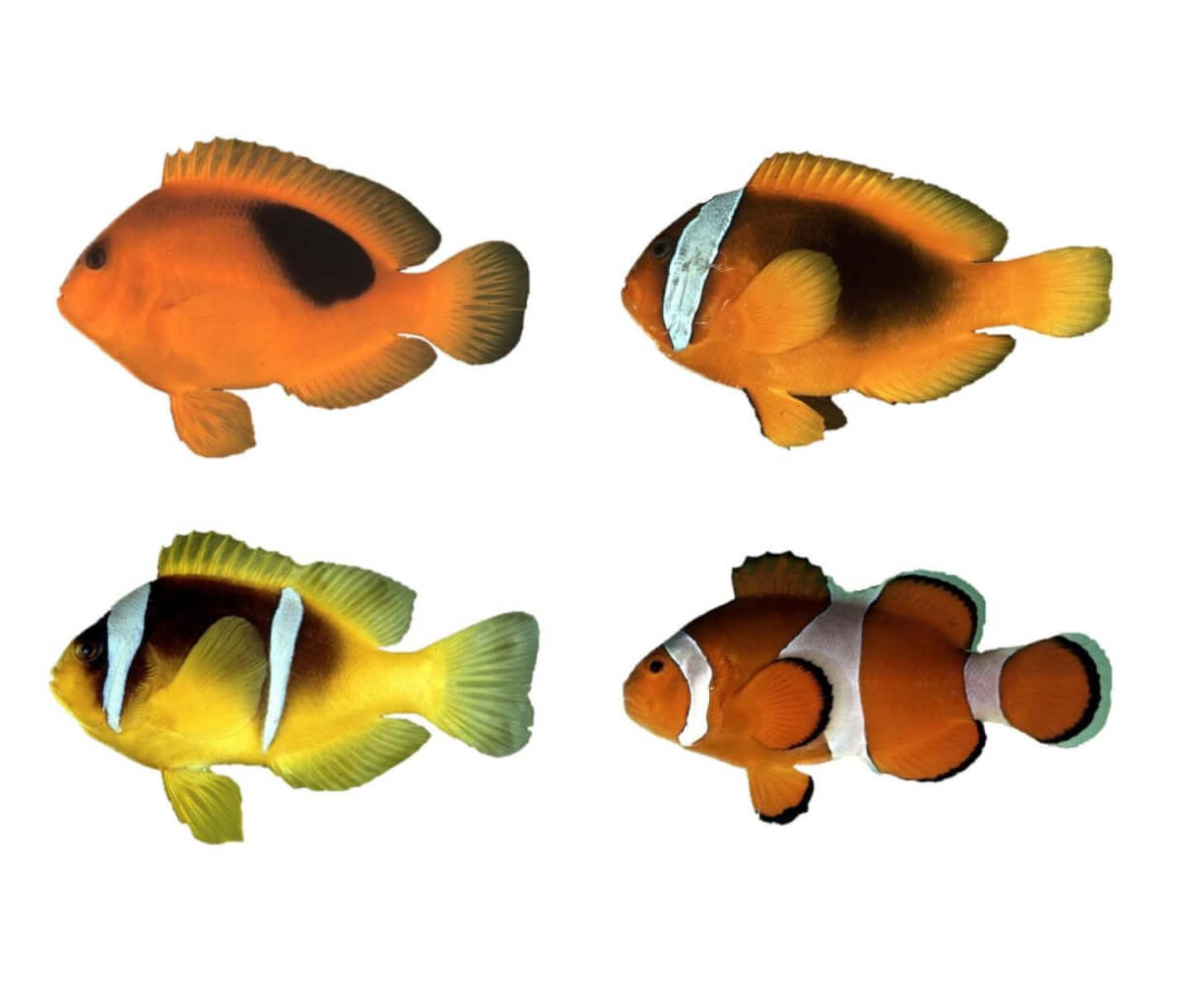

In experiments, scientists observed the reaction of these orange fish to the same or similar species of fish with one to three characteristic white stripes. They found that clownfish count the stripes on other fish and display aversion towards those with three stripes, like themselves, and to a lesser extent, fish with two stripes. However, they generally ignore those with one or no stripes.

The study, conducted by Kina Hayashi from the Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology and her team, demonstrates the clownfish’s impressive counting ability. Contrary to Pixar’s depiction of Nemo and his peers as timid and welcoming, real clownfish vigorously defend their anemone homes from intruders. While some anemonefish species cohabit peacefully with different species, cohabitation with their own species is often unwelcome.

Anemonefish species, sharing the same habitat, display various stripe patterns, ranging from three vertical white bars to none. Previous research has shown that coral reef fish, including clownfish, develop stripes for identification within a crowd. However, the researchers aimed to understand how anemonefish distinguish between their own and other species.

Dr. Hayashi and her colleagues raised a group of clownfish from eggs, ensuring they had no prior exposure to other anemonefish species. At six months-old, the team recorded the young clownfish’s reactions to different species, including Clarke’s anemonefish, orange skunk clownfish, and saddleback clownfish, as well as their own species. The common clownfish showed the most aggression towards their own species with three white bands, engaging in confrontations up to 80 percent of the time.

Intruders from other species faced less hostility. The orange skunk clownfish, with a distinct white line but no sidebars, faced the least confrontation. Meanwhile, the Clarke’s and saddleback clownfish, with two and three white bars, respectively, experienced mild bullying.

“Common clownfish attacked their own species most frequently,” Dr. Hayashi reports in a media release.

Despite observing frequent attacks on their own species, the researchers wondered how clownfish distinguished between their own and others. In further tests, they exposed small groups of young clownfish to models with different numbers of white bands. The fish showed little interest in a plain orange model, similar to their reaction to the orange skunk clownfish. They occasionally nipped at the model with one bar but were more aggressive towards the three-striped models, indicating a dislike for sharing space with similar-looking fish. The two-striped model also received an unwelcome reception.

Dr. Hayashi proposes that the aversion to two-barred fish might relate to their development, as common clownfish initially form two stripes before gaining a third. This suggests that clownfish may view two-striped fish as competitors.

“Anemonefish are interesting to study because of their unique, symbiotic relationship with sea anemones. But what this study shows is that there is much we don’t know about life in the marine ecosystems in general,” says Dr. Hayashi.

The findings are published in the Journal of Experimental Biology.

You might also be interested in: