NOTTINGHAM, United Kingdom — Many people enjoy some blue cheese with their hot wings, but what about green-yellow or red-brown cheese? While those new colors hardly sound all that appetizing, it’s worth keeping in mind traditional blue cheese is already covered in mold. Now, scientists at the University of Nottingham School of Life Sciences explain that they’ve discovered how the classic blue-green veining forms in blue cheese. This is allowing them to create a variety of other fungal strains capable of making cheeses featuring colors ranging from white and yellow-green to red-brown-pink and light and dark blues.

Penicillium roqueforti is the fungus traditionally used all over the world to produce blue-veined cheese such as Stilton, Roquefort, and Gorgonzola. The trademark blue-green color and flavor of that fungus come from pigmented spores formed by fungal growth. Using a complex combination of bioinformatics, targeted gene deletions, and heterologous gene expression, the research team behind these findings, led by Dr. Paul Dyer, Professor of Fungal Biology, uncovered precisely how the blue-green pigment forms.

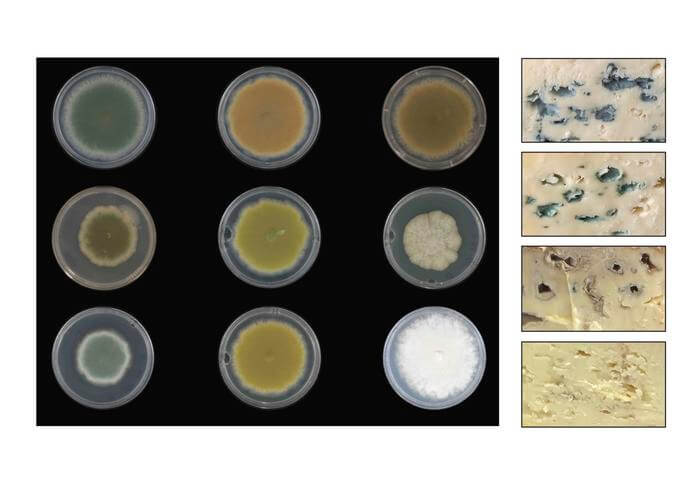

Study authors discovered that a biochemical pathway gradually creates the blue pigments. What starts out as a white color eventually turns yellow-green, red-brown-pink, dark brown, light blue, and finally, dark blue-green. Then, researchers used classic food-safe (non-GM) techniques to “block” the pathway at certain points, thus creating strains featuring new colors capable of being used in cheese production.

“We’ve been interested in cheese fungi for over 10 years and traditionally when you develop mould-ripened cheeses, you get blue cheeses such as Stilton, Roquefort and Gorgonzola which use fixed strains of fungi that are blue-green in colour. We wanted to see if we could develop new strains with new flavors and appearances,” Dr. Dyer says in a university release.

“The way we went about that was to induce sexual reproduction in the fungus, so for the first time we were able to generate a wide range of strains which had novel flavors including attractive new mild and intense tastes. We then made new color versions of some of these novel strains.”

Once the research team produced cheeses with the new color strains, they used a series of lab diagnostic instruments to ascertain what the flavors might be like.

“We found that the taste was very similar to the original blue strains from which they were derived,” Dr. Dyer adds. “There were subtle differences but not very much.”

“The interesting part was that once we went on to make some cheese, we then did some taste trials with volunteers from across the wider University, and we found that when people were trying the lighter colored strains they thought they tasted more mild. Whereas they thought the darker strain had a more intense flavor. Similarly, with the more reddish brown and a light green one, people thought they had a fruity tangy element to them – whereas according to the lab instruments they were very similar in flavor. This shows that people do perceive taste not only from what they taste but also by what they see.”

The research team, including lead postgraduate student Matt Cleere, will now look to start working with cheese makers in Nottinghamshire and Scotland to create new color variants of blue cheese. A university spin-out company called Myconeos has already been established to see if the strains can succeed commercially.

“Personally, I think it will give people a really satisfying sensorial feeling eating these new cheeses and hopefully might attract some new people into the market,” Dr. Dyer concludes.

The study is published in npj Science of Food.