OKINAWA, Japan — An octopus’ brain is on the same wavelength as a human’s — literally, researchers in Japan say. The enigmatic eight-limbed creature is famous for being clever. It can use tools, build dens with rocks and coconut shells, and use tentacles as weapons. Now, scientists are successfully recording their brain waves by implanting electrodes and a data logger directly into freely-moving individuals.

The team identified several distinct patterns, some of which are like those seen in mammals. Others were very long-lasting, slow oscillations that have not been described before. The study, published in Current Biology, sheds fresh light on their behavior and could provide clues to the common principles necessary for intelligence and cognition.

“If we want to understand how the brain works, octopuses are the perfect animal to study as a comparison to mammals. They have a large brain, an amazingly unique body, and advanced cognitive abilities that have developed completely differently from those of vertebrates,” says Dr. Tamar Gutnick, study first author and former postdoctoral researcher in the Physics and Biology Unit at the Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology (OIST), in a media release.

The findings even have implications for alien hunters. Octopuses are regarded as the closest thing to how alien life may be evolving out in space.

In captivity, they can learn to solve puzzles, open jars, and squirt humans they don’t like with ink. They are as smart as the average dog, according to prior studies. However, taking images of their neurons has proven a real technical challenge. They are soft bodied, with no skull to anchor recording equipment.

“Octopuses have eight powerful and ultra-flexible arms, which can reach absolutely anywhere on their body,” Dr. Gutnick continues. “If we tried to attach wires to them, they would immediately rip it off, so we needed a way of getting the equipment completely out of their reach, by placing it under their skin.”

The international team settled on lightweight trackers designed to investigate brain activity of birds during flight. They adapted them to be waterproof devices, but still small enough to easily fit inside the creatures. Low-air environment batteries allowed up to 12 hours of continuous recording.

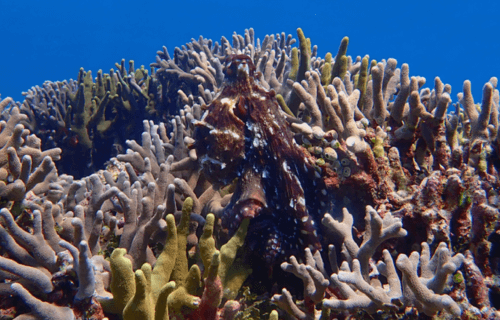

The researchers chose a species called Octopus cyanea, more commonly known as the day octopus, due to its larger size.

The team anaesthetized a trio of octopuses and implanted a logger into a cavity in the muscle wall of the mantle. They also implanted electrodes into an area of the brain called the vertical lobe and median superior frontal lobe which is the most accessible. It is also believed to be important for visual learning and memory.

Once the surgery was complete, the animals were returned to their home tank and monitored by video. After five minutes, the octopuses had recovered and spent the following 12 hours sleeping, eating, and moving around as scientists recorded their brain activity.

The logger and electrodes were then removed and data synchronized to the video. Researchers have not yet been able to link brain activity patterns to specific behaviors as they didn’t require the animals to do specific tasks.

“This is an area that’s associated with learning and memory, so in order to explore this circuit, we really need to do repetitive, memory tasks with the octopuses. That’s something we’re hoping to do very soon!” Dr. Gutnick explains.

The method can be used in other octopus species to discover how they learn, socialize, and control the movement of their body and arms.

“This is a really pivotal study, but it’s just the first step,” adds Prof. Michael Kuba, who led the project at the OIST Physics and Biology Unit and now continues at the University of Naples Federico II.

“Octopus are so clever, but right now, we know so little about how their brains work. This technique means we now have the ability to peer into their brain while they are doing specific tasks. That’s really exciting and powerful.”

These creatures belong to a group known as cephalopods, which also include squid and cuttlefish. Scientists have long wondered how they turned into the brainiest of the invertebrates, rivalling mammals.

Octopuses have similarly complex “camera” eyes to humans. They are unique among invertebrates with both a central brain and a peripheral nervous system, capable of acting independently. They are also very curious and can remember things. Scientists note that octopuses can recognize people and actually appear to like some more than others. Scientists believe they even dream, since they change color and skin structures while sleeping.

Interest in octopuses is growing worldwide. They appear to be a form of intelligence that developed entirely independently of our own.

South West News Service writer Mark Waghorn contributed to this report.