TORONTO, Ontario — The oldest known jellyfish fossil, dating back more than half-a-billion years, has been discovered in the Canadian Rockies. The 505-million-year-old fossil, found in the Burgess Shale, belongs to a free-swimming predatory jellyfish named Burgessomedusa phasmiformis. Impressively preserved, the fossil showcases the creature’s capability to seize substantial prey with its tentacles.

The animal, composed of 95 percent water, belonged to a group known as medusozoans, named after their resemblance to the snake-haired Greek mythological figure, Medusa.

Present-day medusozoans include species such as box jellyfish, hydroids, stalked jellyfish, and “true” jellyfish. They are part of one of Earth’s oldest animal groups, Cnidaria, which also encompasses corals and sea anemones. The discovery of Burgessomedusa demonstrates that large, swimming jellyfish with bell or saucer-shaped bodies had already evolved over 500 million years ago.

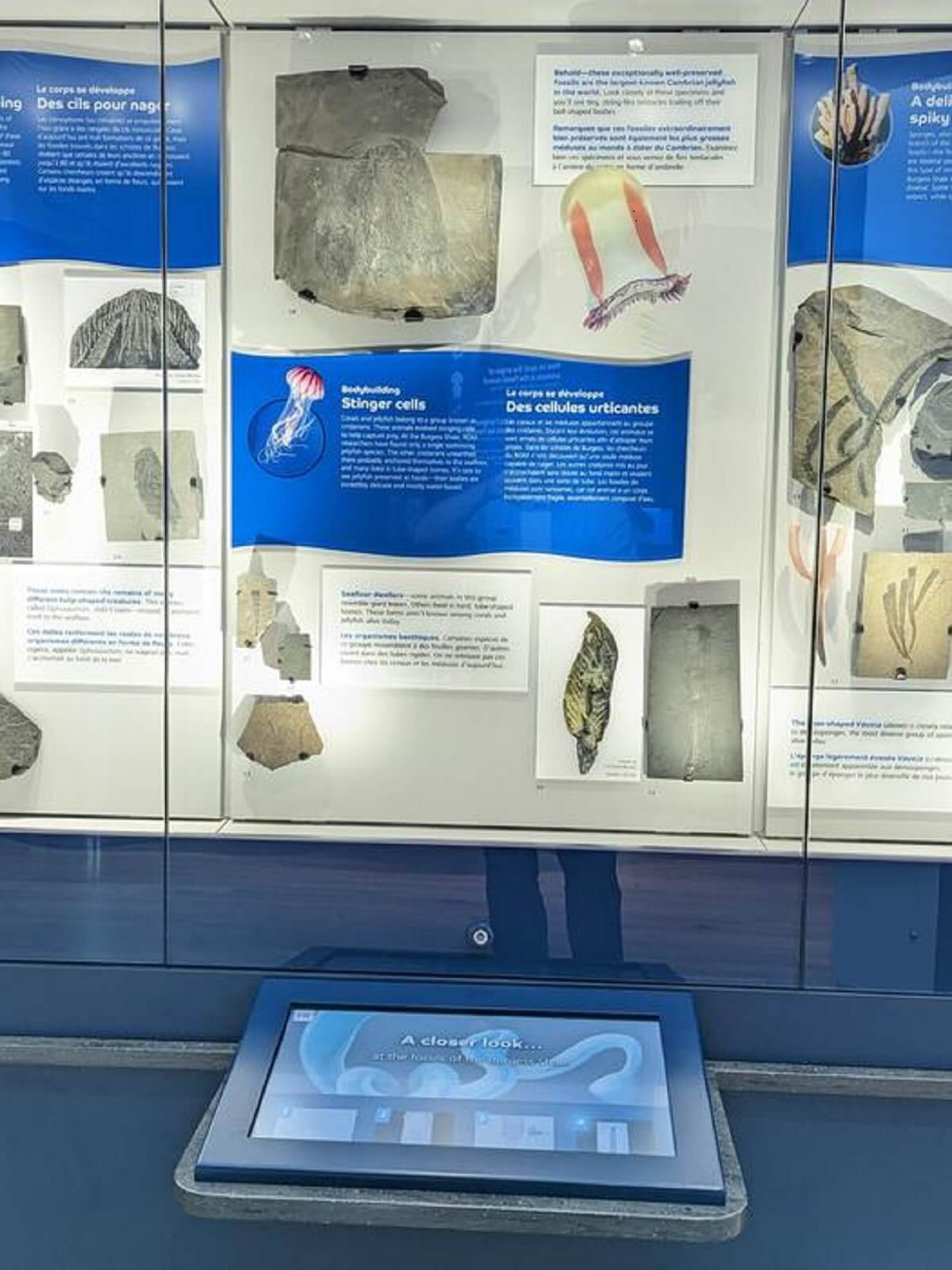

The Burgess Shale fossil site, situated in the Yoho and Kootenay National Parks in southwestern Canada, is famous for its exceptional preservation of soft body parts in fossils. This UNESCO World Heritage Site, designated in 1980, also houses well-preserved Burgessomedusa fossils.

The Royal Ontario Museum (ROM) boasts nearly 200 specimens, primarily discovered in the late 1980s and 90s. The specimens, some of which are over 20 centimeters in length, reveal intricate details of internal anatomy and tentacles, enabling researchers to identify Burgessomedusa as a medusozoan.

The findings add complexity to the understanding of the Cambrian food chain, showing that predation wasn’t solely limited to large swimming arthropods like Anomalocaris, a peculiar “abnormal shrimp” also found in the Burgess Shale.

“Although jellyfish and their relatives are thought to be one of the earliest animal groups to have evolved, they have been remarkably hard to pin down in the Cambrian fossil record,” says Joe Moysiuk, a Ph.D. candidate in Ecology & Evolutionary Biology at the University of Toronto, in a media release. “This discovery leaves no doubt they were swimming about at that time.”

Cnidarians, a group containing more than 11,000 species of aquatic animals found in both freshwater and marine environments, have complex life cycles with two body forms: a vase-shaped body known as a polyp and a bell or saucer-shaped body, known as a medusa or jellyfish. The evolutionary history of the free-swimming medusa or jellyfish isn’t well understood, despite the existence of fossilized polyps from rocks 560 million years old.

“Burgessomedusa adds to the complexity of Cambrian foodwebs, and like Anomalocaris which lived in the same environment, these jellyfish were efficient swimming predators,” adds Dr. Jean-Bernard Caron, a co-author of the study and ROM’s Richard Ivey Curator of Invertebrate Palaeontology.

Fossils of jellyfish of any kind are extremely rare. Consequently, their evolutionary history is primarily based on microscopic, fossilized larval stages and molecular studies of living species. The Burgessomedusa phasmiformis fossils are currently on display in the Burgess Shale section of the recently opened Willner Madge Gallery, Dawn of Life, at the ROM in Toronto, southeastern Canada.

The study is published in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B Biological Sciences.

You might also be interested in:

- 150 million-year-old marine fossil named after Ukraine President Volodymyr Zelensky

- Newly uncovered fossil may have been the first vampire squid with 10 arms

- Genes from a squishy sea creature could unlock ultimate anti-aging treatment

South West News Service writer James Gamble contributed to this report.