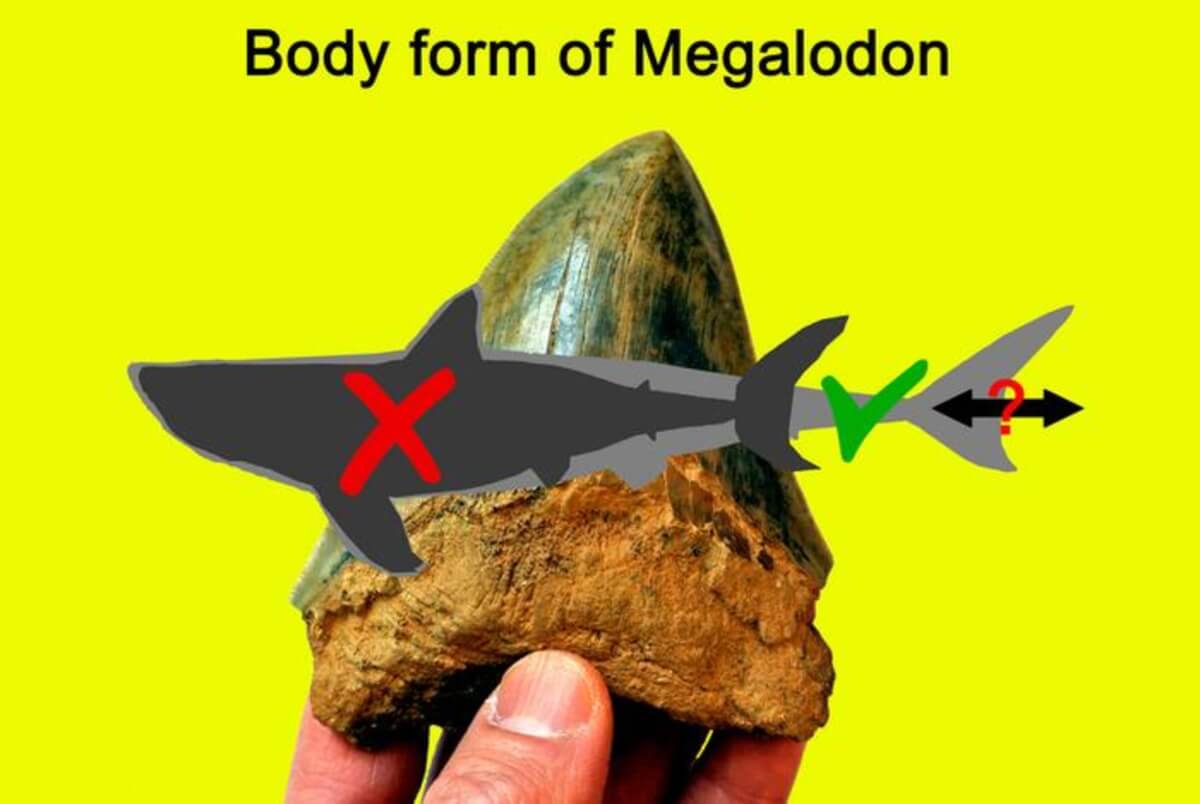

New study suggests the prehistoric shark was likely long and thin, as opposed to a monstrous version of a great white.

RIVERSIDE, Calif. — “The Meg” movies might need a redo. A recent study from University of California-Riverside (UCR) scientists has transformed the scientific understanding of the megalodon, a colossal shark that roamed the oceans until 3.6 million years ago. Contrary to previous beliefs, this prehistoric giant was more slender than previously thought, reshaping our knowledge of its behavior, impact on ancient marine ecosystems, and the reasons behind its extinction.

The megalodon, often depicted as a massive, stocky creature in popular culture, including movies like “The Meg” and “Meg 2: The Trench,” was thought to reach lengths of 50 to 65 feet. The allure of the megalodon is undeniable, primarily due to its gigantic teeth, the only substantial evidence of its existence. Incomplete fossil records led to comparisons with the modern great white shark, but much larger and far more fearsome. But what did this colossal creature really look like?

“Our team reexamined the fossil record, and discovered the megalodon was more slender and possibly even longer than we thought. Therefore, a better model might be the modern mako shark,” says study first author Phillip Sternes, biologist at UCR, in a university release. “It still would have been a formidable predator at the top of the ancient marine food chain, but it would have behaved differently based on this new understanding of its body.”

The study involved 26 scientists globally. The team’s “eureka moment” came upon realizing discrepancies in estimated lengths for the same megalodon specimen. They conducted a new comparison of megalodon vertebra fossils against those of living lamniform shark relatives, using CT scans of a great white shark’s vertebral skeleton.

“It was still a giant, predatory shark. But the results strongly suggest that the megalodon was not merely a larger version of the modern great white shark,” says Sternes.

This revised understanding of the megalodon’s body impacts not only our view of the shark but also its ecological role in ancient oceans. A slimmer, more elongated body implies a longer digestive canal, potentially enhancing nutrient absorption and reducing the frequency of feeding.

“With increased ability to digest its food, it could have gone for longer without needing to hunt. This means less predation pressure on other marine creatures,” notes Sternes. “If I only have to eat one whale every so often, whale populations would remain more stable over time.”

A New Approach to Megalodon’s Appearance

Three critical pieces of information have recently emerged, reshaping our understanding of the megalodon:

- Geochemical Evidence of Endothermy: The megalodon was likely regionally endothermic, similar to modern lamnid sharks. This means it had a unique internal system to maintain a stable body temperature, beneficial for a large predator.

- Placoid Scales and Cruising Speed: The discovery of megalodon’s placoid scales, particularly their interkeel distances, suggests a slower cruising speed compared to modern lamnids, including the white shark.

- Endothermy in Other Sharks: Studies on other lamniform species, like the basking shark and smalltooth sand tiger, show endothermic characteristics, challenging previous assumptions that only fast-swimming sharks like the white shark were endothermic.

The study also offers a new perspective on the Megalodon’s extinction. While some scientists believe a decrease in prey led to its demise, Sternes proposes another theory.

“I believe there were a combination of factors that led to the extinction, but one of them may have been the emergence of the great white shark, which was possibly more agile, making it an even better predator than the Megalodon,” explains Sternes. “That competition for food may have been a major factor in its demise.”

International researchers believe that this new understanding of the Megalodon will have far-reaching implications for our knowledge of ancient marine life and its influence on today’s oceans.

“Now that we know it was a thinner shark, we need to reinvestigate its lifestyle, how it really lived, and what caused it to die,” says Sternes. “This study represents a major stepping stone for others to follow up on.”

The study is published in the journal Palaeontologia Electronica.

So many assumptions in science today. Theories don’t make fact, no matter how many or who believe them. I’m not saying one is right or wrong. I just know that if one card is removed from your houses structure, the rest of it comes crashing down.