NEWCASTLE, England — A team of astronomers from multiple European institutions has made a groundbreaking discovery of so-called “shooting stars” on the Sun. The findings come from observations made by the European Space Agency’s Solar Orbiter (SolO), which revealed meteor-like fireballs as part of the spectacular plasma formations.

Coronal rain is not comprised of actual water; rather, it is a condensation process where some of the Sun’s fiery material coalesces due to sudden, localized temperature drops. The outermost layer of the Sun’s atmosphere, known as the corona, consists of gas heated to millions of degrees. Rapid temperature drops in this layer result in super-dense plasma clumps that can span up to 250 kilometers in width. These plasma balls then plummet back toward the Sun at speeds exceeding 100 kilometers per second, due to the force of gravity.

“The inner solar corona is so hot we may never be able to probe it in situ with a spacecraft,” says lead author Patrick Antolin, Assistant Professor at Northumbria University in Newcastle, in a media release. “However, Solar Orbiter orbits close enough to the sun that it can detect small-scale phenomena occurring within the corona, such as the effect of the rain on the corona, allowing us a precious indirect probe of the coronal environment that is crucial to understanding its composition and thermodynamics.”

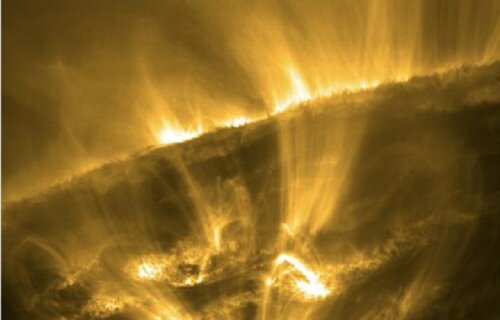

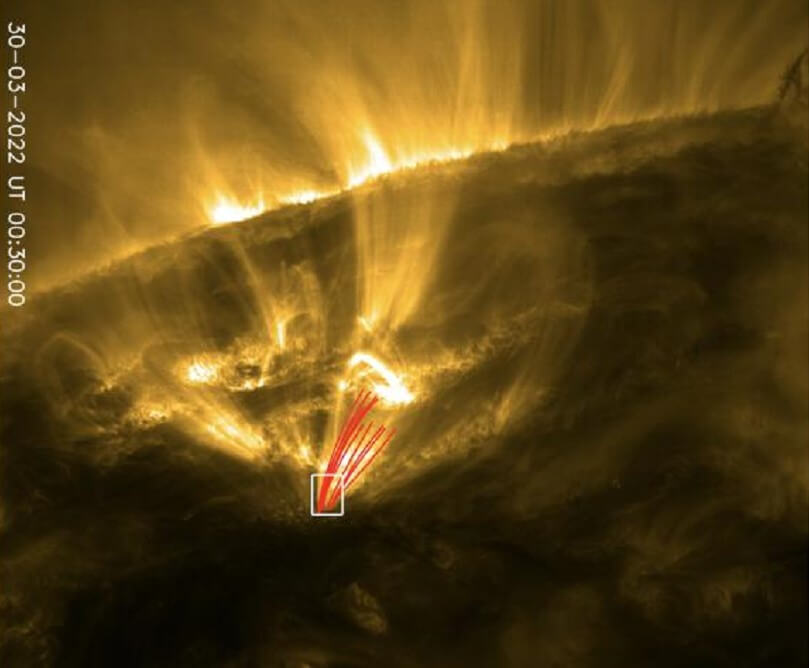

(credit: Patrick Antolin. Background image: ESA/Solar Orbiter EUI/HRI)

The study focuses on SolO’s inaugural close approach to the Sun. In the spring of 2022, the orbiter ventured to within 49 million kilometers of the Sun—just a third of the distance between the Earth and the Sun—capturing the most detailed images ever obtained of the solar corona. The spacecraft not only captured the first ultra-high-resolution images of coronal rain clumps but also observed a spike in gas temperature and compression below them. These spikes indicate brief periods where the gas heats up to a million degrees.

On Earth, shooting stars occur when meteoroids—space objects ranging from dust grains to small asteroids—enter our atmosphere at high speeds and disintegrate. Some manage to reach the Earth’s surface, forming craters. However, the Sun’s corona is thin and has low density, so it does not erode the plasma clumps significantly, allowing most to reach the Sun’s surface intact. This is the first time their impact has been observed.

Unlike Earth’s shooting stars, which produce tails through a process called ablation, the Sun’s shooting stars don’t produce tails. This is because the Sun’s magnetic field partially ionizes the falling gas and channels it along magnetic field lines. These act like enormous tubes that direct the gas, making the phenomenon harder to capture.

SolO’s observations have also corroborated earlier research, showing that coronal rain is far more widespread than previously believed. “If humans were alien beings capable of living on the Sun’s surface, we would constantly be rewarded with amazing views of shooting stars,” jokes Antolin, “but we would need to watch out for our heads!”

The research was presented at the National Astronomy Meeting (NAM 2023). It is published in a special issue of the journal Astronomy & Astrophysics.

South West News Service writer Dean Murray contributed to this report.