DURHAM, N. C. — Biologists at Duke University compared the eyesight of hundreds of species to find out which can see the best, and where humans fit into the animal kingdom of sight. Humans had among the best eyesight out of the species the researchers studied.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the range of eyesight ability across species is wide. In the study, the Duke researchers found a difference of 10,000 times between the best eyesight and the worst eyesight.

Clarity of images, called vision acuity, is a relatively rare gift in the animal kingdom. While humans pale in comparison to other creatures, such as cats, in the ability to see in the dark and to distinguish fine color differences, we possess some of the best vision acuity on Earth.

Out of the 600 species of insects, birds, mammals, fish, and other animals studied, humans see the world in better clarity than most. Animals “see the world with much less detail than we do,” says first author Eleanor Caves, a Duke postdoctoral researcher, in a media release.

Caves’ study measured vision acuity in cycles per degree, which describes how many pairs of black and white parallel lines animals can discern within one degree of their field of vision before the lines turn into a wash or smear of gray.

The research team also examined the eye anatomy of different species to form a baseline estimate of acuity. They paid close attention to the spacing and density of light-sensing eye structures, and sometimes conducted behavior tests to find out how well different animals could see.

Human eyes can pick up 60 cycles per degree — about four to seven times greater than a dog or cat — with chimpanzees and other primates closely related to us at similar levels. A person considered legally blind can’t see greater than 10 cycles per degree.

Several birds of prey, such as the wedge-tailed eagle of Australia, can see 140 cycles per degree. It’s why some eagles can spot a small animal, such as a rabbit, while soaring thousands of feet above the ground.

Conversely, most birds see fewer than 30 cycles per degree, which is also similar to fish.

“The highest acuity in a fish is still only about half as sharp as us,” says Caves.

Meanwhile, most insects can’t see more than one cycle per degree, with a 10,000-fold difference between species with the sharpest version and those with the worst.

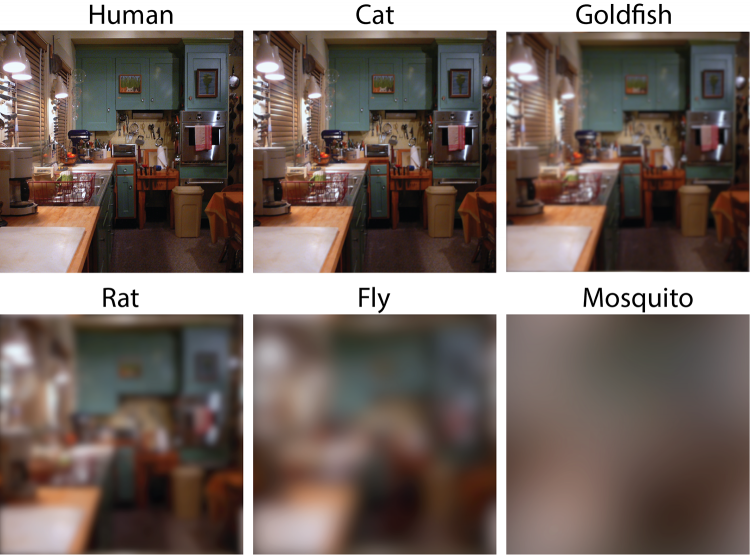

Using special software called “AcuityView,” the researchers took images of wildlife and recreated them to appear as they might for certain species with varied acuities. The findings challenge previous research suggesting the function of certain visible features on certain species, such as a butterfly or spider. Some believe that patterns on a butterfly’s wings are meant to deter birds from eating them and others say they’re used to woo potential mates. But the findings from this latest work could prove otherwise since many birds would instead just see a blur.

“I don’t actually think butterflies can see them,” notes Caves.

Similarly, the finely-weaved zig-zag patterns seen in webs of orb spiders are believed by some to actually attract small insects. But the study shows that the webs are practically invisible to houseflies and other tiny pests.

“The point is that researchers who study animal interactions shouldn’t assume that different species perceive detail the same way we do,” concludes Caves.

The study was published in the journal Trends in Ecology & Evolution.