FAIRBANKS, Alaska — The journey of a woolly mammoth that roamed the Earth 14,000 years ago is helping scientists piece together the history of ancient human settlements in Alaska. Researchers from the University of Alaska-Fairbanks (UAF) and McMaster University in Canada are providing new insights into the migration patterns of these early humans who crossed the Bering Land Bridge, thanks to the iconic Ice Age species.

The study was centered around the female mammoth Élmayųujey’eh, named by the Healy Lake Village Council. Her tusk, discovered at the Swan Point archaeological site in Interior Alaska, has become a key to understanding her life and the lengthy journey she undertook through Alaska and northwestern Canada.

Researchers employed isotope analysis to reconstruct Elma’s travels. This technique involves studying chemical markers in an animal’s diet and environment that are recorded in bones and tissues. Mammoth tusks, in particular, are excellent for such studies as they show visible growth layers, allowing scientists to trace a chronological record of the mammoth’s life.

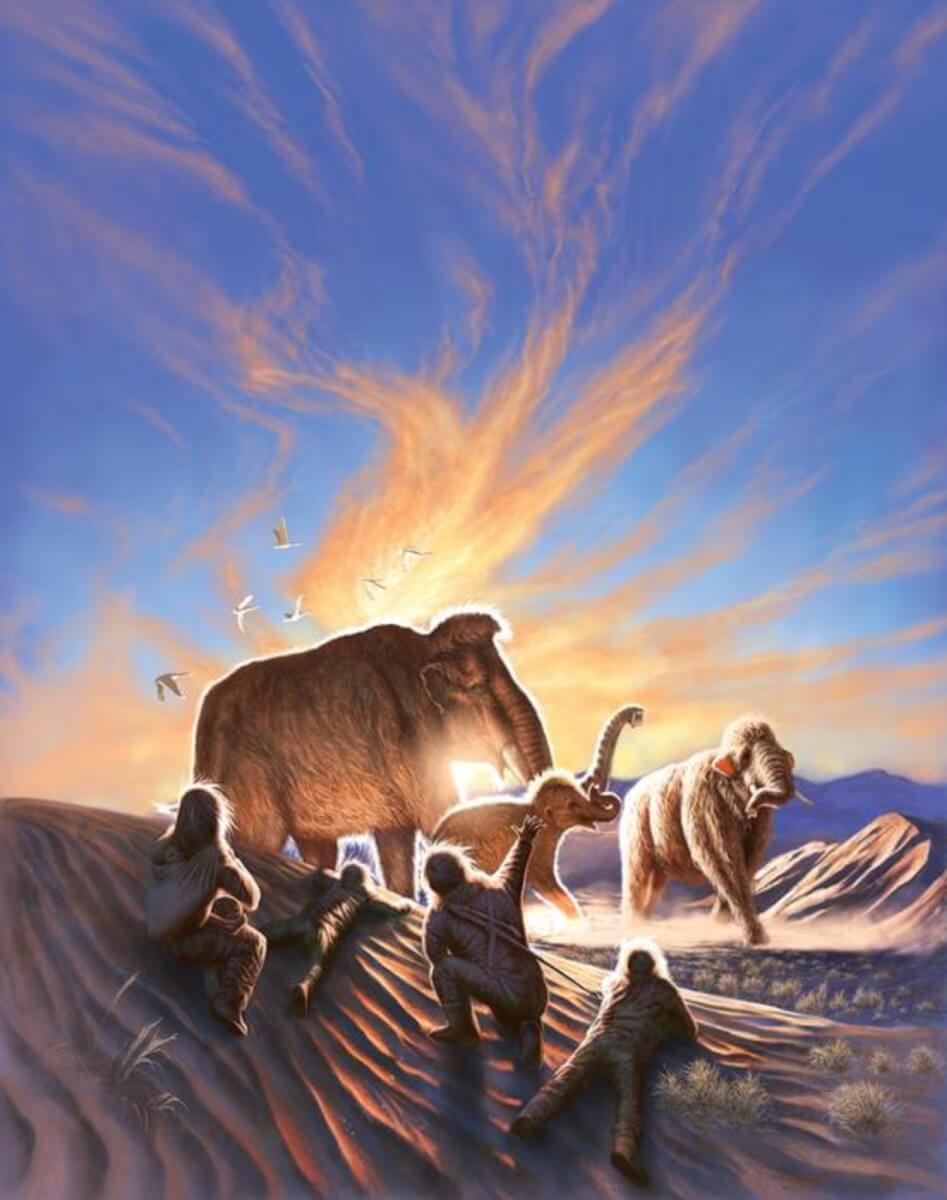

The findings were striking. Elma’s path closely matched the densest concentration of archaeological sites in Alaska, suggesting that early human settlers strategically placed their hunting camps in areas frequented by mammoths. The discovery of Elma’s tusk, alongside evidence of human activity, such as campfires, stone tools, and butchered remains, further supports this theory.

“This is a fascinating story that shows the complexity of life and behavior of mammoths, for which we have very little insight,” says evolutionary geneticist Hendrik Poinar, director of the McMaster Ancient DNA Center, who led the team that sequenced the mitochondrial genomes of eight woolly mammoths found at Swan Point and other nearby sites to determine if and how they were related, in a media release.

The evidence indicates a pattern consistent with human hunting of mammoths. The coexistence and interactions between mammoths and humans in this region are now clearer than ever.

Elma’s journey wasn’t unique. It closely mirrored that of a male mammoth who lived 3,000 years earlier, revealing consistent mammoth movement patterns over millennia. Elma was around 20 years-old when she died.

“She was a young adult in the prime of life. Her isotopes showed she was not malnourished and that she died in the same season as the seasonal hunting camp at Swan Point where her tusk was found,” says study senior author Matthew Wooller, director of the Alaska Stable Isotope Facility and a professor at UAF’s College of Fisheries and Ocean Sciences, in a university release.

This discovery sheds light on a time of significant environmental change. As the Ice Age ended, the landscape in Interior Alaska was transitioning from a grass- and shrub-dominated steppe to a more forested terrain. This change fragmented the mammoths’ preferred habitats, potentially making them more vulnerable to hunting by humans.

“Climate change at the end of the ice age fragmented mammoths’ preferred open habitat, potentially decreasing movement and making them more vulnerable to human predation,” notes Ben Potter, an archaeologist and professor of anthropology at UAF.

The research offers a unique glimpse into the past, highlighting the dynamic interplay between early humans and woolly mammoths in Alaska’s ancient landscape.

“This is more than looking at stone tools or remains and trying to speculate. This analysis of lifetime movements can really help with our understanding of how people and mammoths lived in these areas,” concludes Tyler Murchie, a recent postdoctoral researcher at McMaster. “We can continue to significantly expand our genetic understanding of the past, and to address more nuanced questions of how mammoths moved, how they were related to one another and how that all connects to ancient people.”

The study is published in the journal Science Advances.

Well, I guess you can map a wider range of colors onto the narrower range of colors that we see, but it won’t really be quite what the animals who can perceive all those colors see. Most colors will have to be altered to make the mapping work,

Or will it? If they still have just three types of cones, I guess you can create a picture of a scene that would produce the same responses in our cones that the actual scene produced in the cones of the animals. Maybe that’s what they are doing. If the animals have four or more types of cones, that won’t work. And how polarized light would be represented, I don’t know. Polarized light is not “invisible” to us, of course, it’s just indistinguishable from non-polarized light.