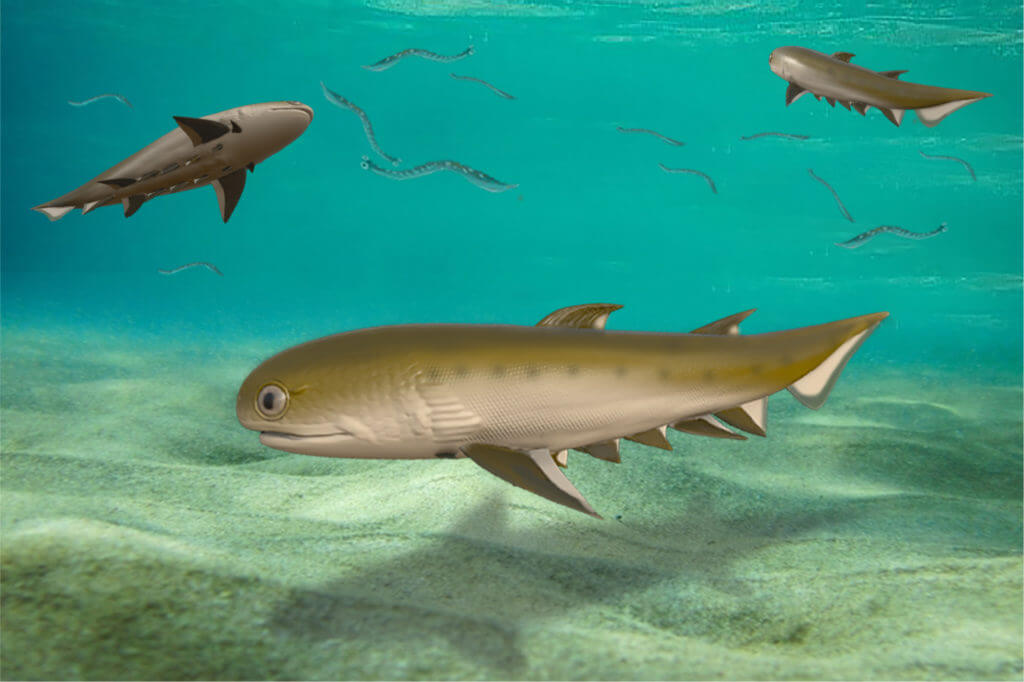

BEIJING, China — In a “jaw-dropping” discovery, a new study finds that humans evolved from an armored shark that swam the oceans 439 million years ago. The bizarre beast, named Fanjingshania renovata, is also our oldest jawed ancestor, according to an international team.

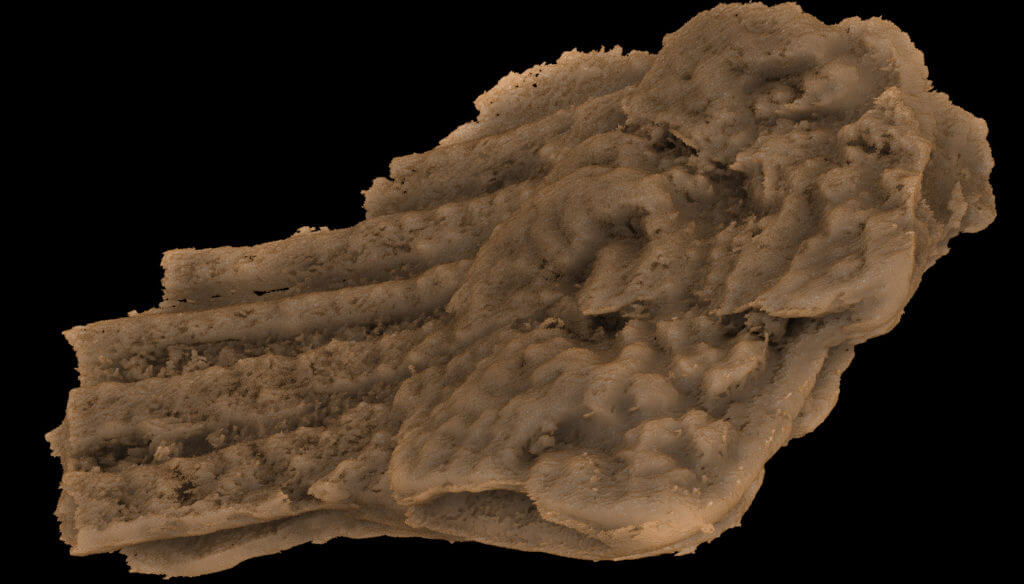

The study finds it was covered in bony plates and bristled with multiple pairs of fin spines that sets it apart from living descendants. The primitive fish has been reconstructed from thousands of tiny skeletal fragments unearthed at a prehistoric animal graveyard in southern China.

“This is the oldest jawed fish with known anatomy,” say Professor Zhu Min from the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology (IVPP) of the Chinese Academy of Sciences in a media release. “The new data allowed us to place Fanjingshania in the phylogenetic tree of early vertebrates and gain much needed information about the evolutionary steps leading to the origin of important vertebrate adaptations such as jaws, sensory systems, and paired appendages.”

Fanjingshania was an early member of the modern gnathostomes, meaning “jaw-mouths.” They include tens of thousands of living vertebrates ranging from fish to birds, reptiles, and mammals.

(Credit: FU Boyuan and FU Baozhong)

It belonged to a group known as chondrichthyans, cartilaginous fish such as sharks and rays. Fanjingshania reached up to two-and-a-half feet long. It lived before the split between the earliest sharks and the first bony fishes — an evolutionary lineage that eventually included humans.

It was also a member of the acanthodians, which went extinct about 250 million years ago. Its shoulder girdle is key to pinpointing its position in the evolutionary tree of early vertebrates.

The international team found a group known as climatiids possess the full complement of spines seen in Fanjingshania. Moreover, in contrast to normal dermal plate development, the pectoral ossifications of Fanjingshania and the climatiids are fused to modified trunk scales.

This is seen as a specialization from the primitive condition of jawed vertebrates, where the bony plates grow from a single ossification center. The bones of Fanjingshania show evidence of extensive resorption and remodeling typically associated with skeletal development in bony fish, including humans.

“This level of hard tissue modification is unprecedented in chondrichthyans, a group that includes modern cartilaginous fish and their extinct ancestors,” adds lead author Dr. Plamen Andreev, a researcher at Qujing Normal University. “It speaks about greater than currently understood developmental plasticity of the mineralized skeleton at the onset of jawed fish diversification.”

Cartilaginous fish, which today include sharks, rays, and ratfish, diverged from the bony fishes more than 420 million years ago. However, little is known about what the last common ancestor of humans, manta rays and great white sharks, looked like.

The resorption features of Fanjingshania are most apparent in isolated trunk scales that show evidence of tooth-like shedding of crown elements and removal of dermal bone from the scale base. Thin-sectioned specimens and tomography slices show this resorptive stage was followed by deposition of replacement crown elements. Surprisingly, the closest examples of this skeletal remodeling are found in the dentition and skin teeth, or denticles, of extinct and living bony fish.

In Fanjingshania, however, the resorption did not target individual teeth or denticles, as occurred in bony fish, but instead removed an area that included multiple scale denticles. This peculiar replacement mechanism more closely resembles skeletal repair than the typical tooth or denticle substitution of jawed vertebrates.

The results, published in the journal Nature, have profound implications for our understanding of when jawed fish originated.

They align with morphological clock estimates for the age of the common ancestor of cartilaginous and bony fish, dating it to around 455 million years ago, during a period known as the Ordovician.

The findings tell us that the absence of undisputed remains of jawed fish of Ordovician age might be explained by under-sampling of sediment sequences of comparable antiquity. They also point towards a strong preservation bias against teeth, jaws, and articulated vertebrate fossils in strata coeval with Fanjingshania.

“The new discovery puts into question existing models of vertebrate evolution by significantly condensing the timeframe for the emergence of jawed fish from their closest jawless ancestors. This will have profound impact on how we assess evolutionary rates in early vertebrates and the relationship between morphological and molecular change in these groups,” concludes Dr. Ivan J. Sansom from the University of Birmingham.

South West News Service writer Mark Waghorn contributed to this report.